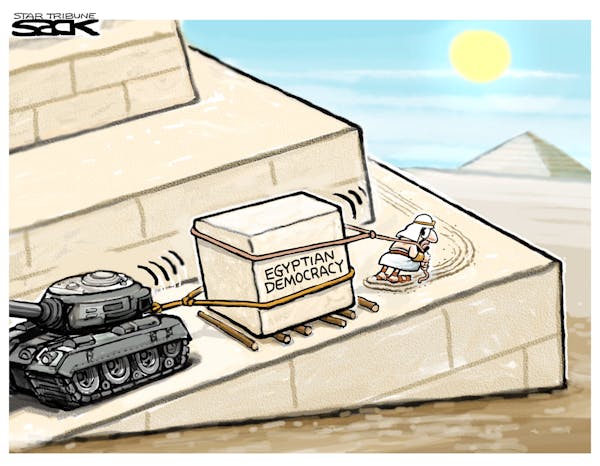

In case you still thought Egypt's coup was leading to democracy, the violent destruction of Muslim Brotherhood protest camps and the appointment of 19 generals as provincial governors — occurring more or less simultaneously — should cure you of that appealing fantasy. When generals come to power, even if they are initially motivated by the ideal of restoring democracy, the attraction of remaining in power for as long as it takes to establish a military order tends to be decisive. When a regime that generals have deposed was democratically elected, as it was in Egypt, the odds of restoration are even more remote.

Western democrats want to love the Egyptian liberals who bravely helped bring down Hosni Mubarak and then misguidedly followed the same playbook to sink the legitimately elected Mohammed Morsi. But the emerging reality poses a puzzle about those Egyptian liberals and their country's future: Why in the world did thoughtful believers in democracy think that it was a good idea to stage protests that would invite the army to take out Morsi? And what, if anything, can be done now to get democracy back on track in Egypt?

Some supporters of the anti-Morsi protesters claim that the liberals naively hoped that they would see a repeat of what happened after the protests that brought the Mubarak regime to its knees: The military would intervene to take out the president, then move quickly to stage free and open elections. In support of this diagnosis of naiveté is the fact that the military didn't seize power after the coup against Mubarak. Perhaps, then, it was conceivable that the military would act in the public interest once again.

The trouble with this idealistic view is that the army didn't especially want to hold elections after Mubarak was removed. It was pressured into it by the Muslim Brotherhood, which was — alongside the army — the only other well-organized, disciplined and effective national organization. The army and the Muslim Brotherhood both expected that the Islamists would prevail in elections. The army didn't much like that, but it feared that if it didn't allow elections in the wake of the Arab Spring, it would lose public support. It therefore gambled on cutting a deal with the Brotherhood.

Once public protests peaked against Morsi and the Brotherhood, however, the army no longer had to worry that suppressing the only force capable of balancing it would be seen as totally unpopular. To put it bluntly: The liberal protesters in the streets gave the army cover to take out the Brotherhood. The protesters should have seen it coming.

A more cynical view is that the liberals knew the army would suppress the Brotherhood — and wanted it to happen. The Brotherhood could be counted on to like elections as long as it was winning them, but its commitments to liberal rights, as opposed to electoral democracy, were paper-thin. After the drafting of the Islamic-oriented constitution — which was ratified in a national referendum — liberals feared that the Egyptian public was willing to take a chance on the Brotherhood. That result frightened liberals, who by then had lost parliamentary and presidential elections. Knowing they couldn't win at the ballot box, liberals were happy to let the army take care of their electoral nemesis.

Either way, the question remains: Can democracy be salvaged in Egypt? At some not-very-distant point, the generals will stage an election, if only to satisfy U.S. lawmakers who are embarrassed by the blatant antidemocracy of the coup and think that the Foreign Assistance Act — essentially repudiated by the Obama administration — actually bans continued aid. The Muslim Brotherhood may be formally banned from participating, but in any case, its senior leadership will be either in prison or disqualified from running, or both. Its members may well boycott the election.

Should the liberals run for office, taking advantage of a field cleared of the most popular party in the country? If they do, they'll have to claim that the coup was all about democracy, and they'll have to say that it is the Muslim Brotherhood's own fault that it won't or can't run.

If the liberals participate and elect some candidates — even a president — they will soon see that the army has no interest in relinquishing meaningful power to them. So long as the Brotherhood still exists — and it has endured repression for almost a century — the liberals' position in power will be completely dependent upon the military's good offices in excluding the Brotherhood.

In exchange, the military will expect obedience from the elected civilian leadership on the issues it cares about: not just defense and foreign policy, but also domestic policy insofar as it involves preserving the prerogatives of the army and its self-controlled business empire. Oh, and free speech, which will have to be controlled to keep the Islamists from denouncing the government as illegitimate. And free assembly, which will have to be prohibited so the Muslim Brotherhood doesn't organize more protests. Freedom of religion? Forget about it.

The upshot will be that the liberal rights sought by the protesters won't exist — not just for the Brotherhood but also for them. Their principles gone, they will be tarred by the brush of collaboration. And eventually, the Islamists will be back. The next time, though, it won't be by the ballot.

---------------------

Noah Feldman is a law professor at Harvard University.

Cut down on electronic waste in Minnesota

In Minnesota, statistical gloom amid the hope of a progressive-led boom