When Marla Waseka converted the gracious Franciscan nunnery northwest of St. Cloud to a boutique lakeside resort and retreat in 2008, the nitrate levels in her well were low. A few years later they were so high she had to warn her guests not to drink the water. And when authorities warned they'd shut her down if it weren't fixed, she spent $12,000 to drill a deeper well for clean water.

Now Minnesota is poised to roll out its first-ever strategy to protect drinking water from the farm fertilizers that carry nitrates — one of Minnesota's worst pollution problems. What makes Waseka angry is that it won't do nearly enough to clean up the water.

"This should be a much higher priority," said Waseka, who has followed the state's proposed plan since her well problem. "Incurring a cost is one thing. Not being able to continue in business is another."

And though they have expressed support for the strategy in carefully couched comment letters, Minnesota's top environmental officials agree with her. They say the state's long-awaited nitrogen fertilizer management rule will place farmers' yields above groundwater protection — and continue to put drinking water at risk.

"The unfortunate part is that it's impossible to raise crops without an impact on groundwater," said Randy Ellingboe, head of the Health Department's drinking water section.

The contradiction between supporting farmers and protecting water may be inevitable in a state where agriculture contributes $19 billion annually to the economy. Every year, farmers plant 16 million acres with corn and soybeans, using close to 800,000 tons of fertilizer.

State officials acknowledge that some of it is still going to leach into water even if farmers follow the Agriculture Department's new rules and all the best guidance to prevent it.

Bruce Montgomery, the scientist who helped develop the department's new strategy, said the proposed rule will generate a shared responsibility for water quality, through the creation of local agricultural committees that will educate farmers on best ways to reduce the impact of nitrogen.

For the first time, Montgomery noted, the state will have authority to step in with the few farmers who don't adopt them voluntarily. But, he said, the state doesn't have legal authority to dictate what landowners grow — an interpretation of state law that some legislators and environmental groups may challenge.

What's clear, said Ellingboe, is that the costs of keeping drinking water safe will "continue to be borne by others."

2,000 tainted wells

In the last decade, nitrate contamination in drinking water has emerged as one of Minnesota's most vexing water pollution problems. Above 10 parts per million — the maximum allowed by state and federal health standards — nitrates present a risk to pregnant women and infants. Babies who drink water or formula made with contaminated water can develop a condition known as blue baby syndrome, which reduces the oxygen supply in their blood. Some research also suggests a link to increased risks of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in adults.

According to the state Health Department, there are several dozen community public water systems with source nitrate consistently above the maximum safe level, although they either treat the water or take the source off-line to prevent or resolve a violation. Multiple cities, from Hastings to Perham, Minn., have had to install costly water-treatment technology, at a cost of about $3,500 per household.

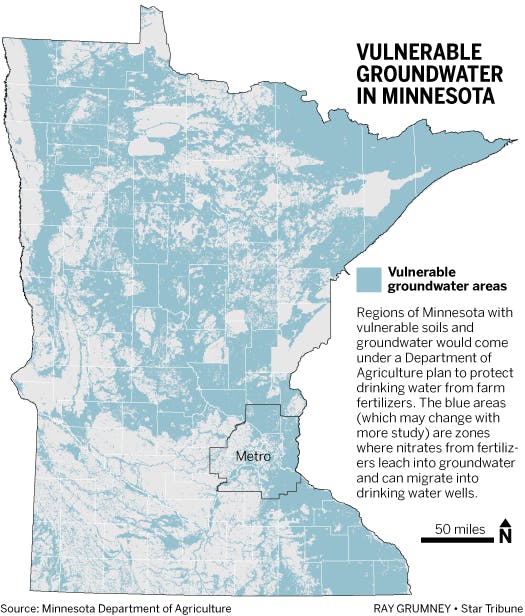

An Agriculture Department survey of 20,000 private wells found that one in 10 is at or above the legal limit for nitrates, primarily in southeastern and central Minnesota.

Homeowners can choose whether to do something about elevated nitrate levels in their own wells. But cities, nursing homes, churches and businesses like Waseka's Olive Branch Retreat in Grey Eagle are required to address it.

One reason nitrate rates are rising, even though farmers now use far less per acre than they once did, is that global markets drove up the amount of Minnesota farmland devoted to corn and soybeans. As a result, fertilizer sales have continued to climb.

But those economics mean "we are growing a system that is not sustainable environmentally," said Gyles Randall, a retired soil scientist at the University of Minnesota who analyzed the new rules for the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, which has questioned their effectiveness.

He said the new strategy will help: It presses farmers to use less nitrogen and apply it at the right time. Even so, he added, the minimum amount of fertilizer to maximize a farmer's yield is more than enough to contaminate Minnesota's water.

'Economic destruction'

Anchored in the state's 1989 Groundwater Protection Act, the rule is Minnesota's first effort to regulate farmers' use of fertilizer. It's expected to be complete in late 2018, after another public comment period.

Even so, it has generated fierce debate across the state.

In hundreds of comments submitted to the Agriculture Department after 17 community meetings this year, many farmers vehemently objected to a proposed ban on fertilizer applications in the fall and on frozen soils. Research has shown that much of the fertilizer ends up in the water under such conditions, and it is the least beneficial to corn.

"One rule does not fit all," wrote Terry Eidem of Felton, echoing a common refrain. He grows sugar beets, he said, and he can't do all his applications in the spring.

Some even said that in high nitrate areas, they might be forced out of business. "If the karst area of southeast Minnesota is going to be forcefully returned to acres and acres of cow pasture, I want to sell … before the general public knows what economic destruction is going to occur," said Todd Stockdale of Le Roy.

Kirby Hettver, president of the Minnesota Corn Growers Association, said farmers are grudgingly coming to accept the prospect of a rule, and that it will drive them to better manage nitrogen.

"We want to reduce the environmental impact — and remain sustainable from a yield and profitability standpoint," Hettver said.

Environmental groups, however, say the rule fails in its primary mission. It doesn't even kick in until local wells show rising nitrate levels, they note, and by then it's too late.

Officials from other state agencies and some legislators also note that the rule fails to address areas like Dakota County, where drinking water is already contaminated and the majority of farmers already use fertilizer best practices.

Officials from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency said even the best fertilizer management doesn't always achieve the drinking water standard. They're pressing for more aggressive measures in high-nitrate areas, such as requiring farmers to idle some land or plant cover crops that hold nitrogen on the land.

Ultimately, said Randall and others, protecting Minnesota's water might require a more diversified agricultural landscape — one that includes more grains, grass and cattle.

But Montgomery said that's out of the state's hands.

"Corn and soybeans is not going to go away," he said.

Montgomery said he's confident the strategy will work because it taps the willingness and ability of farmers and local communities to solve the problem together. Their ingenuity, combined with new technologies, will provide solutions — but it might take a generation to see results, he said.

"It's a huge problem, and you wonder if there is hope," he said. "But then you see what growers are doing."

Josephine Marcotty • 612-673-7394

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries

St. Cloud house vies for Ugliest House in America