How exhausting was that?

Anyone who sits through "Fela!" may be forgiven for feeling wrung out after two-and-a-half hours of ecstatic Afrobeat music, pulsing dance, emotional turmoil and epic resolution. This full-throated proclamation of a singular human life, crafted by director/choreographer Bill T. Jones, opened Tuesday night at the Ordway Center in St. Paul.

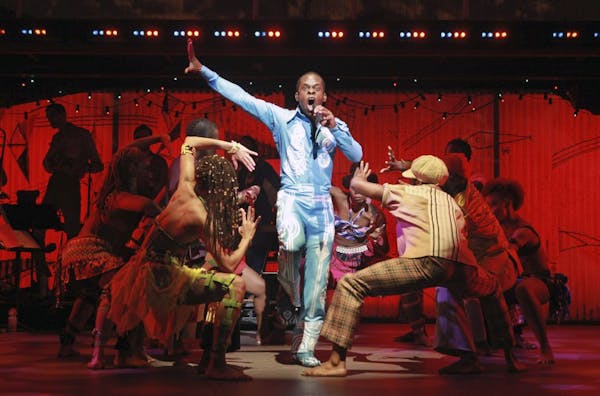

Actor Sahr Ngaujah, who played the role on Broadway, radiates prodigious charisma and energy as the Nigerian singer/activist/shaman/iconoclast. How on earth Ngaujah, nominated for the 2010 Tony, did not win the award is a mystery.

Fela Anikulapo Kuti was born into a prominent Nigerian family. His father was the first president of the Nigerian Union of Teachers. More importantly, Fela's mother, Funmilayo, led the women's rights movement in Africa. She plays a key role in Jones's show.

Fela (feh-LAH) studied music in London in the 1960s and traveled to the United States, where he discovered within the Black Power Movement a vocabulary for his opposition to Nigerian government corruption and the legacy of European colonialism.

He also found through his travels musical influences that informed Afrobeat. He regularly recorded around the world, but his seminal performances were at Afrika Shrine, his club in Lagos. In 1977, government troops raided Fela's commune, Kalakuta Republic, beat up the inhabitants and set the place on fire. His mother was thrown out a second-story window and later died.

Jones has created not a play, but an event -- proposing that Fela is in concert at the Shrine, following the assault. We are the audience as the brilliantly talented Ngaujah sings, dances and narrates Fela's history.

At times, Jones choreographs chaos into that exquisite theatrical moment in which we fear the show has spun out of control. His work captures the pelvic-driven patterns of West-African movement. Conductor Aaron Johnson and drummer Greg Gonzalez are key accomplices in the mayhem.

That driving energy, though, is difficult to sustain, and the assault takes a toll. "Fela!" can feel long.

There are still reasons to stick with it. Melanie Marshall has a crystalline voice as Funmilayo Kuti, a specter who haunts the proceedings. Her 11 o'clock number, "Rain," is an ethereal paean to endurance. Paulette Ivory notably sings a character who represents the African-American education of Fela.

Fela often said that music was his weapon, his songs provoking repression from the Nigerian government. This messianic sense of himself, a seriousness of mission, is missing from Jones's hagiography. What we have is something approaching ritual -- an artistic meditation elevated by pageantry but devoid of the dramatic engine. That propulsive rhythm kicks up our heartbeat, engages our energy and then sends us out the door spent.