Chaska Sgt. Brady Juell felt terrible, but his hands were tied. He had just arrived at his city's 24-hour emergency urgent care center to check on a young adult with a heroin overdose who had been dropped off by car by someone who then took off.

The patient, who turned blue before being revived, refused to talk to Juell. Federal law prevented the facility from releasing any medical information, and whoever brought the man in clearly wanted to remain anonymous because of potential criminal charges.

Juell's frustrations and possible ways to end this often-repeated scenario were among the issues discussed Thursday at a closed-door summit on heroin in Minneapolis attended by Minnesota's top prosecutors, law enforcement, medical officials and treatment experts. Even the police chief of tiny Pequot Lakes, north of Brainerd, made the long drive south to learn what he could in case the deadly drug invades his community.

Minnesota is one of the first to hold a statewide meeting on heroin, said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Washington, D.C.-based Police Executive Research Forum. Wexler, a longtime police adviser on Minneapolis' most critical crime issues, moderated the event.

Many of those present referred to the state's growing heroin problem as a public health epidemic that should be addressed in the same way as any infectious disease. U.S. Attorney Andy Luger reiterated his office's newest strategy — going after smaller heroin dealers instead of waiting for bigger shipments. In a policy shift, he encouraged police to consider presenting cases involving drug overdose deaths against dealers to his office instead of to a county prosecutor, because a federal conviction guarantees a longer sentence.

"We want to make Minnesota an inhospitable place to do business," Luger said. "Many parts of the country have missed the boat on how to deal with heroin. It's not going to happen here."

Hennepin County is on pace to pass last year's highest total of 56 heroin overdose deaths. In 2013, the county reported 132 deaths from opioids, which means a possible combination of heroin, OxyContin, methadone and other opiates were found in a victim's body.

Since it became legal last month for first responders to distribute the drug Narcan, many have administered doses of it to temporarily counteract a potentially lethal overdose of prescription painkillers. A Duluth police official said when he recently tagged along with officers during their shift, he witnessed Narcan saving a life within the first two hours.

"Narcan has been given to people as young as 14 and as old as 72," said Dr. Marc Conterato, an emergency medicine physician and head of ambulance services at North Memorial Medical Center in Robbinsdale. "Ten years ago, Narcan was one of the lesser used medicines stocked in an ambulance. Even so, we are prohibited from telling police if we gave somebody the drug."

'Playing Russian roulette'

Many metro-area police departments pointed to the city of Minneapolis as the place where heroin users buy the drug, but trafficking has regional tentacles, said Dan Moren, assistant special agent in charge of Minnesota's Drug Enforcement Administration district. Gang members and Mexican drug cartels play a substantial role, peddling a purer and cheaper product bought by younger clients, he said. Dealers have also found a fresh market on Indian reservations.

"It's like playing Russian roulette with this drug," said Andrew Baker, medical examiner for Hennepin, Dakota and Scott counties. "Users don't know the purity."

A concern repeatedly raised by law enforcement was the inability to "connect the dots" in heroin cases. Plymouth Police Chief Michael Goldstein said agencies are good at tracking down the drugs and dealers, but not at following the money trails that can be key to taking down operations. He asked if the state shouldn't have something similar to the federal government's drug czar to oversee the investigative big picture.

There was story after story of tragic overdose deaths in cities large and small. One official even talked about how some methamphetamine dealers were handing out free samples of heroin in the hopes of triggering addiction.

Minneapolis Police Chief Janeé Harteau passionately advocated for a greater focus on the demand side of the drug problem. People's stereotype of the modern drug user has to change, she said.

"It's soccer moms and college students," she said. "I'm scared to death for my own child."

Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges spent a few minutes offering her perspective on having been sober for 25 years and the impact her addiction had on friends and the community. She vowed "to do whatever I can from my end" to move forward any recommendations to reduce heroin use.

Murder charges

More police departments are now investigating heroin death overdoses as homicides, going after the dealer or person who gave drugs to the victim. The charge is felony third-degree murder, which means the person unintentionally caused a death by either giving or selling the drug. Such cases are difficult to charge, however, because of uncooperative witnesses and a mixture of drugs in the victim's system.

Last March, Minneapolis police were able to get their first heroin-related third-degree murder case charged. Washington County has charged 10 heroin cases since 2012, relying on cellphones and Facebook to provide evidence.

Medical professionals talked about how addiction to prescription painkillers continues to drive the increase in heroin use. The pills are often stolen from medicine cabinets at home and lead to stronger drugs like heroin. Doctors suggested that ways other than pills need to be found to manage pain.

Near the end of the four-hour summit, there was a candid debate on whether somebody who witnesses an overdose should be immune from prosecution if they call 911. A new state law, part of Steve's Law, which permits first-responder use of Narcan, allows limited immunity in such cases.

Hennepin County Sheriff Rich Stanek, who has more than 20 deputies trained to use Narcan, said he sees merits on both sides of the issue.

"Bottom line is that we are in the business to save lives," he said. "It's a public policy issue."

David Chanen • 612-673-4465

Legendary record store site in Minneapolis will soon house a new shop for musicheads

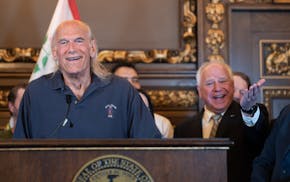

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries