Lilydale Regional Park is off-limits to young fossil hunters while St. Paul officials investigate the landslide that buried four children on a class field trip, killing two of them.

A portion of the park that annually hosts more than 400 groups eager to search the steep bluffs for fossils was closed indefinitely Thursday, just hours after rescue workers recovered the body of 10-year-old Mohamed Fofana from the avalanche of mud, sand and rocks that buried the four students from Peter Hobart Elementary School in St. Louis Park on Wednesday afternoon.

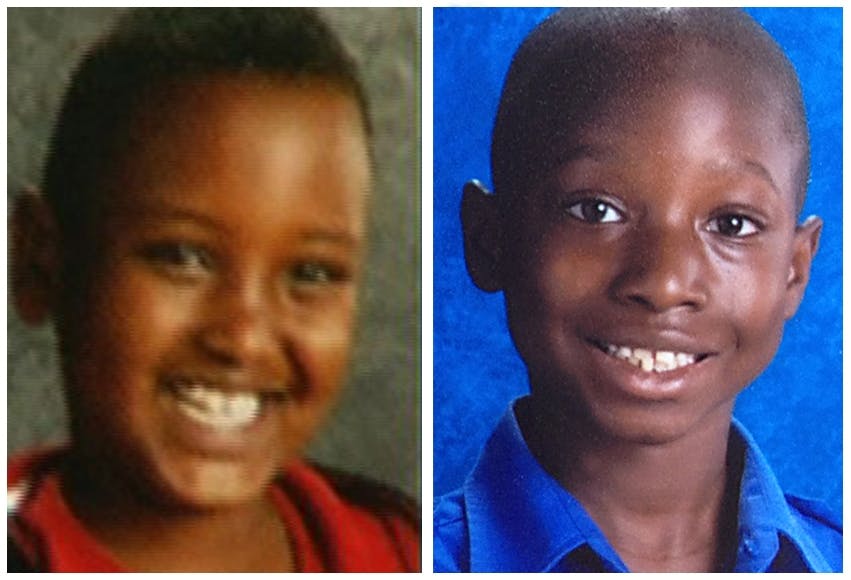

Frantic emergency workers had used shovels, heavy equipment and bare hands to dig 9-year-old Haysem Sani's body from the ground within hours of the slide.

Darkness and dangerous conditions, however, forced them to call off the search for Mohamed and return Thursday morning, when they found his body just 4 feet from where the other boy had died.

Two other fourth-grade students were rescued. One has been released from Regions Hospital; the other remains in serious condition.

Gov. Mark Dayton was scheduled to visit the school at 9:45 a.m. Friday and "address students, faculty, staff and community members about the tragedy," school district spokeswoman Sara Thompson said in a statement.

St. Paul Parks and Recreation director Mike Hahm called the deaths "unprecedented." City officials said they didn't know of any recent landslides in the park, although gradual erosion is common. No significant injuries have been reported in the past five years.

"I've gone in the rain, the sunshine and the snow," said Mayor Chris Coleman, who lives across from the park. "They are wonderful places for children to be able to explore. We had no reason to believe that anything of this nature would occur."

On Thursday, however, Coleman and city officials said they had canceled permits for the next two weeks and would close off the fossil section of the park indefinitely until it was determined to be safe.

Osman Kamara, a friend of the Fofana family, questioned whether the action should have come sooner.

"There has been rain coming several days, so they could have talked before taking them down there," Kamara said. "Something needs to be done."

'Outstanding students'

At a news briefing Thursday afternoon at Peter Hobart Elementary School, St. Louis Park superintendent Debra Bowers called this "an incredibly sad time." Principal Shelley Nielsen said that for many students, this is the first time they've dealt with such a death.

Nielsen said the two boys who died were "outstanding students" who had a "love of life." She said they loved learning and had "very engaged families."

The brief news conference ended with school officials declining to answer questions about whether the trip should have proceeded after heavy rains that left the steep, erosion-prone bluffs saturated with water.

A city-commissioned report on the park released in 2009 listed evaluating erosion as a "high" priority for the city, but four years after its release the city hasn't met that goal.

Parks and Recreation spokesman Brad Meyer said the city has completed half of the six high-priority items, but has not gotten to the erosion evaluation. "We're making our way through those priorities," he said.

The area of concerns cited in the 2009 report did not include the east clay pit, where the students were trapped Wednesday, Meyer said. He said the city will consider looking at erosion around all the clay pits.

The pits have some of the park's most dramatic and sheer drops, largely because of human activity when the brickyard was active and the bluffs were cut.

The east clay pit's slope rises 30 to 40 feet above the fossil dig site, and is the site of a large former kiln that is now fenced off.

Neighbors who frequent the park said signs of erosion and landslides are common, although they could not recall witnessing a slide.

"Whenever we've been in the park with groups, we've always been very careful to keep away from the edge of the bluff because we know it's precarious," said Grit Youngquist, a West Side resident and active leader in the Friends of Lilydale Park group. Youngquist, who moved to the area in 1993, said that a year or two ago, a "pretty significant mudslide" occurred on a key trail that leads to the fossil dig area. Hahm said he was not aware of the incident.

But Youngquist and other Lilydale lovers said the natural wonders of the rugged park are part of its appeal. The slide won't stop them from visiting.

"It's just one of those things where you kind of know what you're getting into," said West Side resident Josh Nelson. "Our kids have spent hours and hours down there."

John Chapman, program director of the University of Minnesota's Erosion and Stormwater Management Program, said erosion is inevitable on the bluffs, but landslides are not a common threat here.

Sudden, dramatic landslides can occur when water upsets surface soil and breaks it loose, or when water moves deep into underground rock. Although Chapman has not been to the site of Wednesday's accident, he said it probably was caused by rainfall dislodging topsoil.

"I'd say the general rule of thumb is … if there's a heavy downpour or a lot of rain over a period of several days, it can generally make a slope less stable and more hazardous," he said. "I don't know that I'd let that inhibit my activities."

Municipal parks are specifically protected under Minnesota statute from claims by park users, but that doesn't mean the coast is clear for the city, even though it requires permit users to sign waivers.

Meyer said schools, not parents, sign off on the fossil dig waiver.

"The law tends to live in a gray area," said Mike Steenson, a professor at William Mitchell College of Law who focuses on Minnesota tort law. "You might assume the general risk of injury, but this is beyond the general risk. … This is a landslide."

Staff writer Rochelle Olson contributed to this report. nicole.norfleet@startribune.com 651-925-5032 Twitter: @stribnorfleet cxiong@startribune.com • 651-925-5034

Robbinsdale shelter-in-place alert accidentally sent countywide

Developer of St. Paul's Keg & Case food hall declares bankruptcy

Wildlife agency: Sturgeon won't go on endangered species list

Minnesotans interviewed to serve on Feeding Our Future trial