Five years ago, when the Bloomington City Council approved a big renovation plan for the Martin Luther Campus nursing home, upset neighbors predicted that the project was just a precursor to an expansion they thought would bring even more traffic to their quiet neighborhood.

In 2011, their suspicions proved true.

Martin Luther came back to the city, asking to add a 67-unit catered-living facility for seniors to a complex that already had 137 nursing-home beds. This time, the city said no.

So Martin Luther's owners sued the city. In December, a Hennepin County District Court judge ruled in the nursing home's favor.

Bloomington is now appealing the decision. While the city has generally been amenable to adding senior housing -- sometimes over the objections of neighbors -- in this case, city officials say, adding to the Martin Luther Campus would bring too much traffic and disruption to the neighborhood.

"Injury to the neighborhood is the main issue," said Sandra Johnson, Bloomington city attorney. "The neighborhood will argue that the last expansion caused significant injury to the livability of the neighborhood, that this would make it even worse."

Martin Luther attorney Tamara O'Neill Moreland said in a statement that she is confident the judge's decision will stand on appeal. "He did an excellent job analyzing the evidence before the city and applying the correct legal standard," she wrote.

For more than 50 years, Martin Luther Campus has operated a skilled nursing facility for senior citizens on E. 100th Street near the bluffs of the Minnesota River. It is about six blocks from Old Shakopee Road, the nearest arterial street. To get to the nursing home, employees, delivery trucks and ambulances must drive on residential streets.

People who live in the neighborhood, including longtime resident Victor Johnson, testified against expansion of the campus. Johnson said recently that he still opposes it.

"The whole thing is, they've outgrown this area," he said. "They have so much going on there, so many people there, so many deliveries, and there's no other way to get in there."

Martin Luther's latest request is to build 67 catered-living units, offering assisted-living with an option of meals, plus a kitchen that will serve the meals. The Bloomington City Council denied the conditional use permit for the expansion on a 4-3 vote, saying it would hurt the neighborhood and be inconsistent with the city's comprehensive plan.

But Hennepin County District Judge William Howard ruled that the city's decision was not supported by facts and there was no tie between the proposal and the "alleged neighborhood disturbances" that were cited in the denial.

Paul Reuvers, the attorney representing Bloomington in the case, disagrees.

"If you look at the map, you have to get through a residential neighborhood to get there," he said. "It is simply not a good location. That's why the city wants these types of facilities next to major roads like Old Shakopee, not meandering through residential neighborhoods."

City Attorney Johnson said the Martin Luther case is the first Bloomington development denial case that's been taken to court in at least a dozen years. But the League of Minnesota Cities, which insures Bloomington in such cases, said such cases are not unusual statewide. Jed Burkett, the league's land-use attorney, said his group sees about 70 land-use lawsuits each year.

"While they're relatively rare, they're quite expensive," he said. "We spend on average over $2.5 million a year on these, with the average case costing about $35,000."

Johnson said that in her view, the court decision goes to the heart of the city's authority to guide development in the most appropriate way. "These issues are near and dear to the hearts of our constituents," she said.

Burkett agreed.

"There's a strong interest in local officials preserving their role as policymakers when it comes to passing and administering land-use ordinances," he said. "The good news is that cities generally win these cases."

Oral arguments on the case will occur in the fall before a three-judge panel. Because the Court of Appeals has 90 days to render a judgment, Johnson said she does not expect to see a decision until the end of the year.

Mary Jane Smetanka • 612-673-7380 Twitter: @smetan

Jill Biden travels to Minnesota to campaign for Biden-Harris ticket

Want to celebrate 4/20? Here are 33 weed-themed events across Minnesota.

Legendary record store site in Minneapolis will soon house a new shop for musicheads

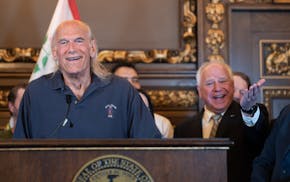

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president