For educators nationwide, the big question surrounding federal stimulus money is: If schools receive a sudden infusion of cash, but will never get it again, what are they supposed to do with it?

For the St. Paul Public Schools, supporting new long-term programs is out, because schools wouldn't have the money to sustain them once the stimulus money is gone. Plugging budget holes is also out, because the federal education department is stressing that the money needs to be used for reform, not just sticking with the status quo.

St. Paul is in line to get $29 million from the federal stimulus package, officially called the "American Recovery and Reinvestment Act," over the next two years.

The complexity of the rules surrounding the money, based on decades of federal education policy, as well as the ephemeral nature of the funds, has led the district to one over-arching theory of how to spend its money: on one-time investments that can have lasting reform benefits for schools.

"It's not an exaggeration to say that there are hundreds and hundreds of pages of federal regulations that apply to these funds," said Matthew Mohs, the director of Title 1 programs for the St. Paul Public Schools. "What we have to do is look at ways in which the funds can be used to essentially build up the system, build up capacity, build up the strength of our teachers, and develop new things can we can support long-term."

Minnesota could get more than $1 billion for K-12 and higher education through the $787 billion stimulus law passed by Congress in February, but most of that won't be new money for schools. Much of it will go through the Legislature, which probably will use it to offset state budget cuts.

Most of what's left will go to schools in the form of federal funding through Title 1, which supports high-poverty schools, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which guides special education.

In St. Paul, 71 percent of the students come from low-income families, and 16 percent are in special education courses.

Earlier this month, Michelle Walker, the district's chief accountability officer, outlined to the school board that the district plans to invest in better teacher training, to help struggling students who might end up in special education, and to improve systems to track student data.

Tom Dooher, president of Education Minnesota, the statewide teachers' union, said that he's seeing a lot of school districts turn to teacher training as a way to spend the money.

Programs that can help more students get ready for college and careers after high school will also be implemented, Walker said. That includes a full audit of the district's curriculum to look at the rigor of different courses and look at how current services for struggling students are faring.

District officials will also be making sure that curriculum in reading and math is consistent within and between schools, to help students who change schools have an easier time with the transition.

The stimulus money will be used to design all of these systems, as well as train staff members on how to use them, instead of supporting them long-term.

Schools that are facing federal sanctions because of years of low test scores will also get more intensive help with teacher training and potential changes in the school's offerings.

Putting all of these new programs in place will require new staff, Walker told the board. In all, the district estimates that up to 80 full-time positions could be "redesigned or newly created" between the programs for low-income and special education students.

But further details on many of the programs are still sketchy, Mohs said. Schools nationwide are treading carefully through the labyrinth of requirements to make sure the money is used wisely.

"These funds just can't be spent on anything," Mohs said. "They need to be spent on things that will leverage change, will improve the system, and improve it in a way long-term, to pay dividends five years down the road.

"We don't want this to be something that when the money runs out, everything we've been doing comes to a screeching halt."

Sarah Lemagie contributed to this report. Emily Johns • 612-673-7460

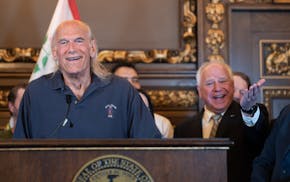

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries

St. Cloud house vies for Ugliest House in America