William Brown loves his four-bedroom house across from a bright red, yellow and blue playground, but the home's assessed value is $82,000 less than it cost to build 11 years ago.

A glance down James Avenue N. helps explain why: His side of the block has seven vacant lots on it.

Brown wants north Minneapolis, his home for 60 years, to stay affordable for his neighbors. But the Army veteran and retired postal worker also wants home values to rise in his neighborhood.

"That's a hard question," said Brown. "You're damned if you do, and you're damned if you don't."

As city planners start to gather opinions on the draft of a sweeping comprehensive plan that aims to promote racial equality and housing affordability, they will encounter skepticism in north Minneapolis that's quite different from wealthier single-family neighborhoods that oppose fourplexes.

Residents over North have already seen city housing initiatives founder, and many believe that homeownership — not a priority of the comprehensive plan — is the real key to building wealth. They live in a part of the city roiled by interlocking worries over housing and development.

"Any policy that is meant to address some of the housing disparities and housing issues but doesn't result in a benefit to communities of color and to communities in north Minneapolis, is just going to be continued institutional racism," said Jeff Skrenes, a mortgage banker, blogger and longtime resident of the Hawthorne neighborhood.

Heather Worthington, the city's long-range planning director, said the comprehensive plan is not a "magic panacea."

"It alone will not fix the problem that we have with deep inequities in this community," Worthington said. "However, as a planning document, it's the first step in fixing the policies that have perpetuated those disparities, and that's all it is — the first step."

The plan, which won't be approved until December, is aimed at increasing density all over the city — allowing fourplexes on any residential lot, allowing six-story buildings on high-traffic streets like West Broadway and part of Plymouth Avenue, and allowing four-story buildings on North Side bus routes such as Penn, Fremont, Lyndale and Lowry avenues N.

The draft comprehensive plan, on which the city is taking comments until July 22, argues that allowing more types of housing in more places will promote racial equity by undoing housing policy that created neighborhoods segregated by income, and often, race.

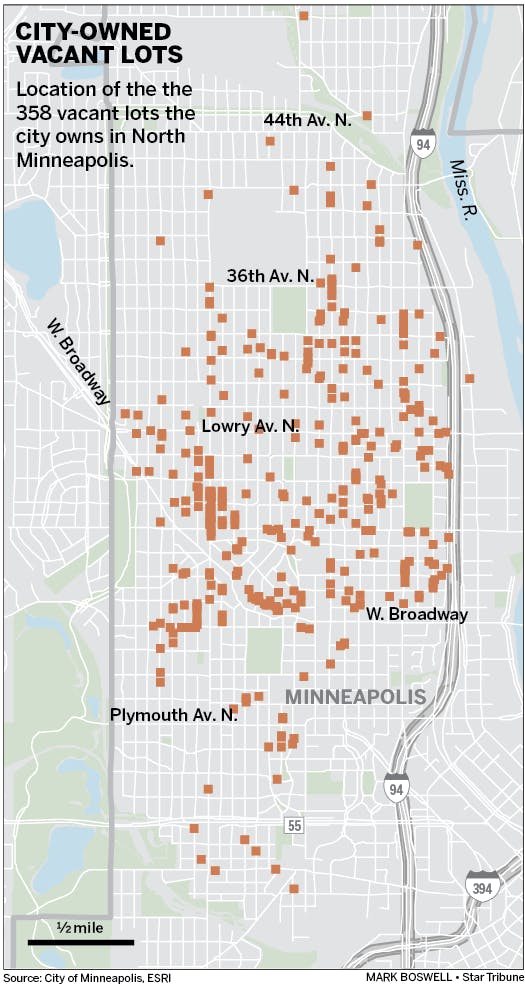

But increased density is low on the list of priorities over North, where 358 city-owned vacant lots sit empty waiting for a buyer, and at least 273 buildings are boarded up.

Despite that evidence of limited demand, north Minneapolis is racked by fear of gentrification — specifically white people displacing black people from neighborhoods rich with family history and pride, said Brittany Lewis, a researcher at the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs at the University of Minnesota.

Lewis bought a house in the Homewood neighborhood two years ago, and when she met one of her neighbors, an older black woman who lived in the house behind hers, the woman was relieved.

"I'm so glad it's you," the woman said to Lewis, who is also black. "She expected me to be white. It's a very strong statement to make to someone you don't even know."

Families of color had looked at other homes in that neighborhood before she moved in, but those houses had ultimately been sold to white people making better offers, Lewis said.

"People are on pins and needles," she said. "They've been seeing a lot of homes sold and flipped."

Changing the physical form of the city will not fix the historic disparities in Minneapolis, she said, nor will allowing more property to be converted into multifamily housing alleviate anxiety over black displacement.

"When you don't own, and you don't believe that you can, and it seems like there are others from outside with more economic power and mobility coming in, why wouldn't you fear?" Lewis said.

Worthington said she acknowledges that people in north Minneapolis may be reluctant to engage with the comprehensive plan, but she asked that they do.

"Please go to the website and comment," she said. "If people feel really strongly, we need to hear from them."

The city launched a program a little over a year ago to try to promote new construction on vacant lots in north Minneapolis, many of them left by the tornado in 2011. Individuals who buy one of the lots and build a new home on it qualify for a $20,000 incentive meant to close the gap between the cost to build a home and the sale price it fetches. Developers qualify for incentives up to $75,000 per unit, but must sell or rent the units to people with lower incomes.

So far, only three people have taken up the city on its offer. Developers have claimed 46 lots. The majority of the homes built through the two programs have been occupied by people of color, said Matthew Ramadan, the project coordinator for the city of Minneapolis.

"The developer has to have a proven track record or a plan in place to work with communities of color, not only the home buyer but their contractors and subcontractors," Ramadan said.

But Queen Kimmons, who runs a nonprofit housing advocacy group and has lived on the North Side since 1979, said too many black people don't know about the program, and if they do, how to apply for the grants. "Most developers and real estate people, they know how to do that," she said.

Kimmons said she just wants the city to help black people, who make up 49 percent of the population in Near North, get to homeownership, which she views as the key to building wealth.

"Here's my stance as a black woman: I believe that black people have been denied wealth historically in Minnesota," she said. "Will this give an opportunity to move black folks forward?"

The fourplex proposal, the component of the plan that has garnered the most attention, has been received coolly in the Jordan neighborhood.

"We already have a problem with the destabilization of neighborhoods because of too much rental," said Deb Wagner, a real estate agent who's lived in north Minneapolis since 1984. The lower half of north Minneapolis, for instance, is 62 percent renter-occupied.

Don Samuels, who represented part of north Minneapolis for a decade on the City Council, said the city has to do a better job dealing with "slumlords." If a block is already challenged by problem properties, adding more rentals will change nothing, he said.

"The city has to double down to make sure that what exists is livable inside the building and creates conditions around it that are livable for the neighbors," Samuels said. "Then you can build pretty much anything, and it will work."

Adam Belz • 612-673-4405 Twitter: @adambelz

Officials say man shot 2 months ago in vacant downtown Minneapolis triplex was victim of homicide

Official who helped MSHSL on pioneering ventures dies at 89

Buy Nothing meets GoFundMe: How a Eden Prairie website aims to 'revolutionize' philanthropy