With a 4-year-old leukemia patient's life on the line, Jessie Harding Fallon kept in touch with his scared family, giving them hope that a marrow donor would be found.

She made posters, put pictures of sick kids on milk cartons, and reached out to black churches and other community groups nationwide in an effort to recruit minority volunteers to be tested and placed in a registry of possible donors.

"We were pioneers," said Liz Quam, who worked with Fallon in the late 1980s and early 1990s to build the National Bone Marrow Registry in Minnesota, when the tissue-typing science was new.

In an era when racial references were particularly sensitive, Fallon recruited much-needed donors from minority communities, using sports figures as speakers, to help build the registry to millions.

"She was beautiful," Quam said. "She was smart. She was funny. She was irreverent. She was very caring. A wonderful mother. And as a minority, she navigated this crazy world with grace."

Fallon, who died June 22 at age 70, also was a pioneer among black women journalists and broke barriers against interracial marriage.

In 1964, Fallon became the first black, and also the first woman, hired as a news reporter at the Grand Rapids (Mich.) Press, a distinction she later repeated as a news reporter and anchor on a Lansing, Mich., television station.

And 44 years ago, she and attorney Frank Fallon were among the first interracial couples to marry after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down state bans on interracial marriages.

"She was genuinely interested in everybody she met," Frank Fallon said. "She would listen to them. She would make them laugh. She would extend herself to them, and she was interested in everything that was going on under the sun. Her interests were so diverse."

Born and reared in Lansing, she studied piano for 12 years and considered becoming a professional musician. Instead, she earned a degree in journalism at Michigan State University.

In the late 1960s, she met Frank when he was a "newly minted" attorney at a news conference and she was a TV reporter grilling him about a housing program, he recalled.

"She decided she would pin my ears back," he said, chuckling. "And that basically went on for 46 years."

She and Frank married in 1969. They were active in Michigan's civil rights community, including the Urban League and Fair Housing campaigns.

They moved to the Minneapolis area in 1975. She worked in public relations for Dayton Hudson Corp. and then stayed home to rear three kids in a big house on Christmas Lake near Excelsior.

She later returned to the workforce, helping to improve access to cancer screening for poor and minority women. She also worked for the Minnesota Adoption Resource Network and served on the boards of Courage Center and the YWCA of Minneapolis, and volunteered in other organizations, as well.

The Fallons lived in Minneapolis for the past 12 years.

"She left her fingerprint on the cosmos," Quam said. "It's just so everywhere. Where she was, it'll be felt forever, everywhere. It's not just me. It's all that she did. We are all better for knowing her."

Other survivors include her children, Jennifer Fallon Montrella, Rebecca Fallon and David Fallon, and one grandson.

Services have been held.

Legendary record store site in Minneapolis will soon house a new shop for musicheads

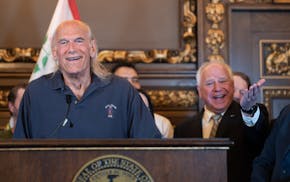

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries