When Tom Bystrom's construction work dried up last month, he pulled his two children from child care and became a stay-at-home dad in the suburbs.

It saved his family about $800 a month. But it created an equal loss for his day care in White Bear Lake.

It's a scenario playing out across the state, where child care providers have become casualties of soaring unemployment and family belt-tightening. Drive by day cares today and you're likely to see signs announcing "Enrolling Now!"

"I've lost five children in the past two months ... which is roughly $2,400 a month," said Penny Shepherd, who runs the licensed family day care that Bystrom's children attended. "It's tough.

"It seems like a lot of parents are looking for something cheaper ... and a lot of them are looking for nontraditional hours because they've taken second jobs."

About 210,000 Minnesota children are enrolled in licensed child care, but their numbers seem to dwindle daily, child care agencies say. Many day cares, especially those located near companies dealing with big layoffs, report that the recent drop in business is worse than they can remember.

The main agency that helps Twin Cities parents find child care reports that calls are down 37 percent from January 2008 to today.

"I don't recall ever seeing that ... and I've worked in referrals 17 years," said Sandy Myers of Resources for Child Caring, based in St. Paul.

The sheer cost of licensed child care is a big reason for the shift. The average cost of full-time child care for a 4-year-old, for example, is $9,300 a year at a child care center and $7,000 a year in family child care, according to recent state surveys.

Some parents are starting up their own informal day cares, which aggravates the situation further, said day care providers. And many parents are turning to less expensive, less experienced referrals from websites such as Craigslist. During the past month alone, 1,700 advertisements were posted from people offering child care or parents hunting for care that was cheaper than market rate.

Bystrom is typical of parents pulling their children from child care. He was earning a decent living as a self-employed mason until the construction industry hit the skids. His wife is a certified public accountant. When the phone stopped ringing this winter, his child care bills were higher than his income.

"We didn't want to pull the kids from Penny's," said Bystrom. "We've known her for years and the kids had friends there. Plus we knew Penny could use the money. But it was the only way we could get through the winter."

Now the couple has a Plan B. His wife will work enough overtime during tax season that she can cut back to three days a week in the summer. Bystrom will jump-start his business in the spring, also working fewer days a week. The arrangement eliminates child care bills.

"Saving $800 a month goes a long way at this point," he said.

Shepherd, meanwhile, is trimming expenses for such things as new equipment, toys and parties for her day care kids, and forgoing purchases for her own family to get through the tough times.

Other family day care providers have picked up the slack by taking part-time jobs, said Katy Chase, executive director of the Minnesota Licensed Family Child Care Association, which represents nearly 12,000 child care homes.

Chase is eying a bill being considered by state legislators that would give home day care providers more leeway to work part time. The idea is not to let home day care providers bail out on the kids, but to leave a bit early to take a second job if needed, said Chase.

Many child care providers are cranking up advertising. They're offering a week of free care, extended night hours and "on call" service. One Elk River provider is even advertising "Evening Child Care on Valentine's Day" to pull in some extra cash.

But advertising could be a waste of money in this environment, said Anna Radloff, director of the Kindercare Learning Center in Maple Grove, which is down 17 children from this year to last -- or about 20 percent of its enrollment.

"We can advertise until we're blue in the face," she said. "People know who we are. They simply don't need us if they don't have jobs."

Even parents who haven't lost their jobs are feeling a child care squeeze. The waiting list for state child care subsidies jumped from 5,400 in July of 2008 to 7,500 in December, state figures show. And those subsidies face a $10 million budget cut under the governor's budget proposal, which worries the child care industry further.

If there is a silver lining, it's that waiting lists for child care have shrunk, infant care -- typically in short supply -- is now available, and the pool of candidates applying for child care jobs is extremely strong, said Chad Dunkley, president of the Minnesota Child Care Association.

Meanwhile many providers are hoping they don't end up in the same unemployment line as their departing clients. Said Shepherd: "I've been in business eight years, and this is the worst I've seen."

Jean Hopfensperger • 651-298-1553

Legendary record store site in Minneapolis will soon house a new shop for musicheads

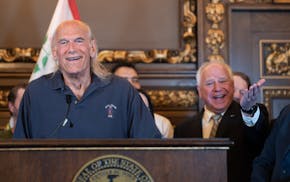

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries