It was a stunning, costly indictment of a state with a vaunted reputation for school innovation and top test scores.

When the Obama administration recently rejected Minnesota's application for up to $250 million in "Race to the Top" stimulus dollars for schools, it cited the state's inability to dump bad teachers, to place the best teachers where they're most needed, or to find faster ways to get teachers into the classroom.

Harsh as that was, it wasn't the only recent blow. In January, the National Council on Teacher Quality gave Minnesota a D- on its annual report card grading teacher policies.

Federal reviewers say Minnesota has trouble even figuring out who bad teachers are. One reviewer wrote that the state's system to assess educators is so ill-defined it deems "97 percent of its teachers to be highly qualified."

The U.S. Department of Education's critique doesn't say Minnesota teachers are terrible. It contends that the system meant to produce and support good educators is broken and that the state may lack the political fortitude to fix it.

But pinpointing the problem, identifying its cause, and finding solutions is the focus of sharp debate among state officials, school administrators and the teachers' union.

"Unless the state and local unions have a willingness to roll up their sleeves, it just isn't going to work," said Charlie Kyte, executive director of the Minnesota Association of School Administrators. "And it would be foolish for the federal government to give a state like that a ton of money."

Representatives with the Education Minnesota teachers union say they've done plenty to police their ranks and to ensure they're doing the best job possible. They say they measure their success by what they hear on the classroom frontlines.

"I think it's very easy to villainize this nameless, faceless mass of teachers," said Mary Cathryn Ricker, president of the St. Paul Federation of Teachers. "But when I talk to parents, they are extremely pleased with their children's teachers. ... It's very easy to buy into this dominant world view of there being an absence of teacher quality. Nobody wants to take control of the quality of the profession more than teachers, and we are doing that."

'Political challenges'

Teacher quality is a hot topic among school reformers. Research points to it as the most important in-school factor influencing a child's education.

Gov. Tim Pawlenty's office blames Education Minnesota, the statewide teachers' union, for preventing the kind of reform favored by the Obama administration. It is one of the top-spending lobbyist groups at the Capitol.

Federal reviewers pointed out that only 12 percent of the state's teachers' unions signed on to Minnesota's application for the $250 million for schools, something that one wrote "may reflect the practical and political challenges the state will face implementing its plan."

But Education Minnesota says Pawlenty and the Minnesota Department of Education are unwilling to listen to teachers about what's needed: Putting more teachers in schools to reduce class sizes, extending the school day or school year where necessary, and finding ways to recruit new teachers, especially teachers of color.

Others point to the conviction that local school boards, not state or federal bureaucrats, should be making the school decisions.

"We're a local-control state," said state Rep. Mindy Greiling, DFL-Roseville, chairwoman of the House K-12 Education Finance committee. "When you combine that with a strong union, the cards are stacked against" the application for more federal money.

Firing teachers

Minnesota "makes it too difficult for districts to dismiss poor performers," the national teacher quality report said.

Teachers who do something awful are easily dismissed. But firing teachers who aren't pulling their weight "is challenging," said Kate Maguire, an assistant superintendent in the Osseo schools.

"You have to have pretty significant and long-term evidence that a teacher is either unwilling or unable to meet a standard of performance," she said.

Teachers' union officials say it's not that hard, and that districts do it regularly.

Barb Kettering, president of the Mounds View Education Association, said that bad teachers are shown the door every year in her district. Often, those with tenure end up resigning, Kettering said.

"Those things don't make the paper," Kettering said. "It makes the paper if they say, 'Mounds View fired 10 teachers.' It's not as dramatic as that."

Pawlenty's time in office has been filled with efforts to overhaul teaching policies. Some mirror the Obama administration's priorities to tie teachers' raises to better student test scores.

A 2004 Pawlenty proposal would have created a class of "superteachers" who could make as much as $100,000 by boosting test scores at struggling schools. That fell by the wayside. A current proposal to require teachers to re-earn their tenure every five years is dead in the water, Greiling said.

The "Q Comp" merit-pay program, a first step toward tying teacher pay increases to performance evaluations and student test scores, did make it into law and is firmly established in 44 school districts. But Pawlenty's administration has said it wishes that program could have gone further, and critics have said it wasn't tough enough in evaluating teachers' skills.

The Obama agenda also supports another idea being debated in Minnesota: allowing people without traditional teaching licenses to teach. But teachers' union officials and some legislators say they're leery of any measure that makes it too easy to become a teacher.

"What we don't want shortchanged is that direct experience working with kids, and learning how to motivate kids, and dealing with groups of kids," said Sandra Skaar, president of the Anoka-Hennepin Education Minnesota teachers local.

Bridging the gap between the current reform agendas and Minnesota teachers looks like a serious challenge.

Part of the problem is trust, said Bernadeia Johnson, Minneapolis' deputy superintendent.

"The reality is we need data and information to make the best decisions about how effective our teachers are being in the classroom with our students," she said. "But there's mistrust, and the idea that it will be used to target teachers."

Emily Johns • 612-673-7460 • ejohns@startribune.com Norman Draper • 612-673-4547 • ndraper@startribune.com

Legendary record store site in Minneapolis will soon house a new shop for musicheads

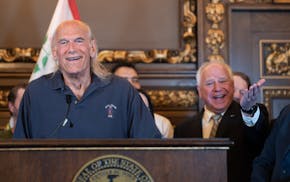

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries