Since the alleged Ponzi scheme involving Tom Petters broke, there have been few more vexing questions inside our newsroom, and among local defense attorneys, than the true identity of one of the participants, Larry Reynolds.

Until this week.

Petters' attorney apparently smoked him out and provided enough detail that our reporters, through dogged legwork, were able to show that Reynolds is in fact Larry Reservitz, a convicted drug dealer and swindler with mob connections from Boston.

Reservitz turned snitch and was rewarded with a new identity, a new name and the freedom to make a nice little lifestyle for himself peddling tennis shoes: $2 million homes. A Ferrari and a Bentley. A voracious and public gambling habit. Oh, and the ability to engage in a multi-billion-dollar Ponzi scheme.

From a distance, it looked like a sweet deal. It's almost enough to hope somebody puts out a mob hit on you.

But Gerald Shur, who wrote the original rules for the federal witness protection program, said participants mostly are assisted in changing their names and relocating. They are given a small monthly stipend, maybe $1,500. "But it's not a reward," said Shur. "While they are receiving assistance, there are certain things they are expected to do."

It's not like parole, where participants must check in regularly, he said, and once they relocate "they start anew and are on their own. Some become successful; others don't."

In other words, the feds didn't set Reservitz up in the fancy digs and lifestyle, Shur speculated. They also do not monitor every move, he said, so it's conceivable Reynolds could have participated in or orchestrated scams without their knowledge. In rare instances, participants can get kicked out for committing crimes, and many have, including murder, though recidivism is lower than for parolees.

•••

Reporters working on this story immediately became suspicious of Reynolds, whose trail disappeared like footprints blown over by desert sand. His Social Security number was issued in Nebraska, with no evidence he ever lived there. The rest?

Poof!

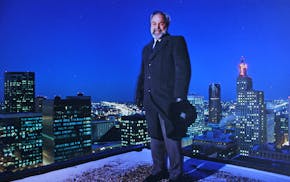

At the time I asked a local defense attorney how he would find out who Reynolds was. "Send the picture to people who are looking for him," he said. "He's a crook being protected by the feds; who cares what happens to him?"

My favorite return call was this guy: "John Shea, author of 'Rat Bastards,' " said the caller, a former member of the Whitey Bulger gang. He didn't recognize Reynolds, but promised to send his photo along the East Coast. "Anything I can do to get a snitch," he said.

We took out ads in the Brockton, Mass., newspaper, and I asked the cop reporter there to circulate his picture at the cop bars. Nothing.

I even sat outside the high-roller tables at the Bellagio in Las Vegas for two nights with a photo of a friend of Reynolds, looking for him. I had more luck on the quarter slots.

•••

Now we know Reynolds' story, and it's a good one. The case against Petters contains strong evidence, including recorded conversations. But Reynolds/Reservitz's background will make an interesting plotline in court.

Reynolds "has pled guilty in court; now you can get him up on the stand and ask him all about his other names and crimes he committed and [say] that he was in witness protection because someone wanted to kill him," said Steven Meshbesher, a defense attorney not connected to this case. "You show all these things we only see on television, not here in Minnesota, and you say Petters is this rube from St. Cloud and that he didn't know anything about this. I'd take that any day."

Meshbesher should know. He represented Petters in the first fraud accusation against him in Colorado, one that foreshadowed future deals. Petters agreed with a New York man to buy some stereos. He never delivered the cash, and the guy had him charged with fraud.

Meshbesher got it dismissed and expunged, and the deal disappeared, just like Reynolds' past. Did Meshbesher play up Petters' rube-roots appeal?

"Absolutely," he said. "But to do that, you have to get him to shut up. So he just sat there."

It worked. Afterward, Meshbesher let Petters be his old self again.

"On the plane home, he worked everybody," Meshbesher said. "He had his arms around the pilots, and everybody knew who he was. I've never seen a more mesmerizing, enigmatic person."

jtevlin@startribune.com • 612-673-1702

Tevlin: 'Against all odds, I survived a career in journalism'

Tevlin: Grateful Frogtown couple fight their way back from fire and illness