On Tuesday, the state's highest court took up the questions underlying one of Minnesota's highest-stakes education lawsuits in years: What does a good-enough education look like, and do the courts have the power to judge whether or not the state has delivered?

The parents and community group that filed the lawsuit in November 2015 say the courts should be able to gauge whether the state failed its constitutional duty to give all kids an "adequate" education. The state argues that the court has no right to stick its nose in the question of education quality.

The suit has the power to reshape school demographics across the metro area for the first time in two decades. The magnitude of that was palpable in the Minnesota Judicial Center courtroom full of education advocates and area attorneys.

The suit, Cruz-Guzman v. State of Minnesota, argues that state officials are shirking their constitutional duty to educate poor and minority students, many of whom attend segregated public schools.

In 2016, a Hennepin County district judge said that parents could sue the state. In March, the Minnesota Court of Appeals threw out the case, saying courts can't define an education quality benchmark. Plaintiffs appealed to the state Supreme Court, which agreed to hear arguments over whether the courts could define education quality.

"Can a segregated school system ever constitute a general and uniform system of education under the Education Clause?" Associate Justice David Lillehaug asked Karen Olson, a deputy state attorney general.

Olson replied that the state Constitution guarantees a general and uniform education, but "uniform does not mean identical."

Dan Shulman, attorney for the parents, pointed to the 1993 Minnesota Supreme Court decision in the school funding case Skeen v. State of Minnesota, which found that the state has to supply enough funds to assure students are adequately educated.

"It is a very small step for this court to find that a segregated education is not an adequate education," Shulman said.

All justices were present at Tuesday's arguments except David Stras, who was recused.

The suit involves only the state and not individual schools, though the complaint calls out the Minneapolis and St. Paul districts. Chief Justice Lorie Gildea asked Shulman why the schools weren't included. Shulman said it's because plaintiffs want relief from the state, which has responsibility.

The courtroom tensed up when Lillehaug began to grill Olson on state education definitions. If a school put kids in study hall all day to read books their parents identify, he asked, is that an adequate education? Olson replied that based on the Constitution, nothing says education must hold a certain quality.

Her responses frustrated a couple of the justices.

"I just have this feeling that I'm asking questions and not getting answers," Lillehaug said.

After oral arguments ended, plaintiff Alejandro Cruz-Guzman and his children hung around the courtroom doors.

"I'm hoping that we're going to get good news," he said.

Beena Raghavendran • 612-673-4569

Legendary record store site in Minneapolis will soon house a new shop for musicheads

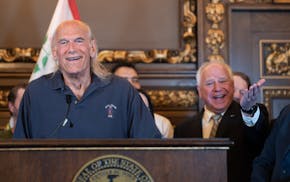

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries