One of the state's most closely watched education lawsuits in years is heading to the Minnesota Supreme Court on Tuesday, accusing state officials of shirking their responsibilities to educate poor and minority students.

The case could prompt dramatic demographic changes in schools, including the first metrowide school desegregation plan in two decades. But before that, the Supreme Court has to weigh in on judicial authority: Can the courts decide whether the state failed in its responsibility to adequately educate students?

A Court of Appeals ruling in March said no, but a trial court judge in 2016 said parents had the right to sue, causing a courtroom ricochet since the seven Minneapolis and St. Paul families and community group first filed Cruz-Guzman v. State of Minnesota in November 2015.

A Hennepin County district judge said in July 2016 that the parents had enough grounds to sue, denying a request from the state and a group of charter schools to throw the case out. In March, the Minnesota Court of Appeals scrapped the case, saying that the courts can't define a standard of quality education. Then plaintiffs went to the state Supreme Court.

The case comes at a tense time for education in the metro area. Elementary students in Minneapolis and St. Paul attend schools that are more racially segregated than they've been in a generation, a 2015 Star Tribune analysis found.

Poverty concentration in schools is linked with lower achievement, the parents' complaint says. Segregation by race makes it worse. Dan Shulman, attorney for the parents, said the case is garnering attention around the country.

"The eyes of the nation are really on the Minnesota Supreme Court now," Shulman said.

Meanwhile, attorneys for the state have said that the plaintiffs haven't pointed out any intentional discrimination and that the suit should be dismissed since it doesn't sue the schools in question.

Integration's past, future

Unlike desegregation cases nationally, Minnesota's doesn't focus on school funding, Shulman said.

The suit also argues that the state let schools carve boundaries that "deliberately increased segregation" as more families of color headed for the suburbs. It says that suburban school districts like Minnetonka market to wealthier white students in nearby districts just as those schools are redoing their own boundaries, which could boost school diversity.

About 20 years ago, Shulman and his son, John Shulman, spearheaded another integration lawsuit from the Minneapolis NAACP. The settlement of that case created the "choice is yours" program, which let low-income students from Minneapolis attend suburban school districts.

That program was successful, Shulman said, but didn't prompt wider desegregation efforts.

So far, several area education advocates have filed amicus briefs, including plaintiffs in the state's hot-button teacher tenure lawsuit, which argues that state laws make it too tough to get rid of "chronically ineffective" teachers. The state Supreme Court will wait to hear that case, Forslund v. Minnesota, until the integration suit is resolved.

School superintendents around the metro have already been chipping away at a plan of their own. After the integration suit was filed, they started surveying parents and students about school equity, caliber and integration issues. Their resulting plan, called Reimagine Minnesota, includes goals like adding in more personalized education and fair allotment of resources.

Even when the integration suit was previously dismissed, school leaders were wedded to these plans.

"The superintendents remained very committed," said Scott Croonquist, executive director of the Association of Metropolitan School Districts, a group that has worked with the school leaders. "They said, 'No, that's irrelevant, we believe that there are very important issues, that we're clearly not succeeding with all students right now.' "

Legendary record store site in Minneapolis will soon house a new shop for musicheads

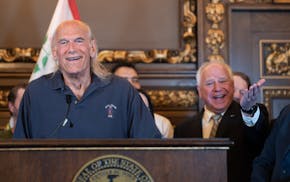

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries