A free well-testing program for Minnesota homeowners has become the latest target in the state's increasingly fractious political battle over water and agricultural pollution.

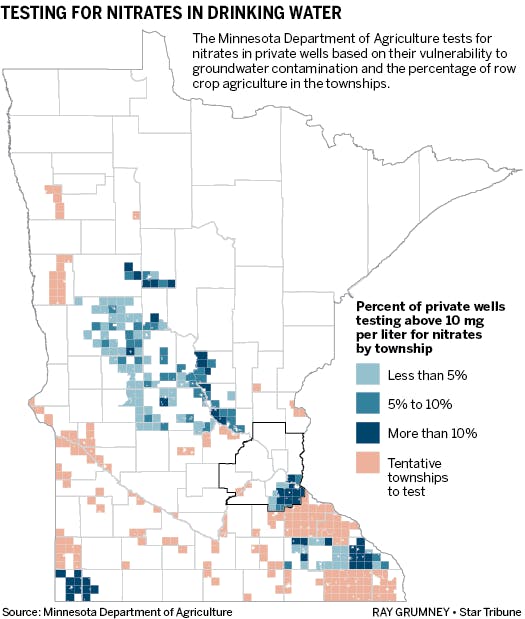

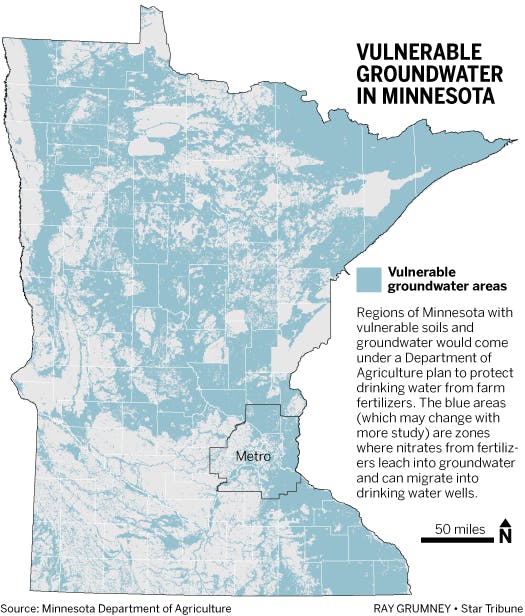

At its December meeting, the Brown County Board of Commissioners in New Ulm declined to adopt a plan that would allow some residents to get their drinking water tested for nitrates and other farm contaminants by the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. The tests are part of a statewide project to assess water quality in private wells in areas that are especially vulnerable to leaching from fertilizers and pesticides — a rising concern in some of parts of Minnesota's farm country.

But in a sign of the uphill fight the state faces, the five commissioners — three of whom are farmers — said they were more worried that the Agriculture Department would use the information to regulate the use of fertilizer — which is remotely possible.

County Commissioner Scott Windschitl, himself a farmer, said he sympathizes with their view, but thought the testing worthwhile.

"My thought was, this is a good thing — we're going to test for nitrates and see if they are there," said Windschitl, who moved to adopt the program. "I want to know it."

His motion died for lack of a second.

The other four commissioners did not respond to requests for comment, but Windschitl said the board seemed to feel that the $10,000 well testing proposal was "tipping toward — well, we already know we will find nitrates and ag is where it's coming from."

Reaction in the community has been divided. Local farm organizations commended the board.

"The [state agency's] efforts … are shameful, because they know there isn't any creditable research to support a linkage of high nitrates in domestic wells with farm field fertilizer or manure use," said a letter signed by representatives from the Brown County Corn and Soybean Growers Association and the Brown County Farm Bureau.

Steve Commerford, a New Ulm crop consultant who attended the board meeting, said the state's intent isn't drinking water protection — it "is to trigger regulations."

The editorial page of the Journal in New Ulm, however, suggested the state's goal is more straightforward.

The commissioners "wondered what the state would do with the information," the newspaper said. "We guess the state would tell people who have bad water that they have bad water so they can get clean water." Turning down the free well testing, it said, is "not wise policy."

Free advice

Dan Stoddard, a manager at the Agriculture Department, said that a wide body of research from the University of Minnesota and elsewhere has proved that fertilizer can and does leach from soil into groundwater. The state's program, he said, gives homeowners important health information about the quality of their drinking water.

"That's one of our goals," he said.

The department has offered well testing for the past few years in parts of the state where farming is prevalent and sandy soils or shallow groundwater are easily contaminated with the chemicals used on crops. The state sends letters to homeowners telling them they can send in water samples for free testing. For those that come back positive, the department sends out experts to conduct further testing and assess the likely source of contamination, which could include septic systems, animal feedlots, shallow or leaky wells — or neighboring cornfields.

The quality of Minnesota's groundwater is crucial — that's where 75 percent of the state's residents get their drinking water. Corn and other nitrogen-hungry crops cover close to 16 million acres of land and use 800,000 tons of fertilizer per year.

So far, 167 townships in 19 counties have participated, primarily in the central and southeast part of the state, with more planned for the coming year. So far, only Brown County has opted not to participate, said state officials.

Of the 20,000 wells tested, one in 10 has been found to have nitrates above the health limit of 10 parts per million. That's the level long established by state and federal regulators to protect infants from a condition called "blue baby syndrome," in which nitrates in breast milk or formula suppress the oxygen supply in their blood. Some research also suggests a link between nitrates and increased risks of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in adults.

Newborns and children

Brown County officials said they don't know the extent of nitrate contamination in their area, but they are concerned about it.

Karen Moritz, the county's health director, said her department offers free well testing for bacteria, arsenic and nitrates to any family with newborns or small children.

"We have a pretty aggressive program," she said. "We teach people that they should not be drinking the water if there are high nitrates."

And it's been a problem in the southwest corner of the county, where the Agriculture Department has proposed well testing. Years ago, the town of Leavenworth undertook a long, expensive search for a new source of uncontaminated water for the community drinking water system. Sylvan Schumacher, chairman of the Leavenworth Township Board, said it cost $30,000 and every resident had to pay $1,000.

"Maybe that's their concern," he said of the commissioners. "It's too much pressure if you got nitrates."

The concern that appeared to be front and center, however, was that the Agriculture Department would someday use well test results to trigger a plan to minimize fertilizer use, part of the state's long-term effort to protect groundwater.

The rule, which has not yet been finalized, would rely in part on private well testing data to initiate a series of voluntary steps to reduce fertilizer use in a contaminated area. Local advisory committees would promote model farm management practices. If after several years a majority of farmers refused to comply, then the state could step in with as yet unspecified regulatory steps.

Environmental groups have been highly critical of the plan because, they say, it won't necessarily reduce fertilizer use enough to protect groundwater. State farm groups have been equally critical for other reasons, including some of those cited by the farmers in Brown County.

"We are not opposed to getting additional information on water quality," said Chris Radatz, executive director of the Minnesota Farm Bureau. "We are concerned about using data from private wells."

Josephine Marcotty • 612 673 7394

This St. Paul native now goes by Kandi Krush, and she body-slams her opponents in the ring

Baseball Metro Player of the Year packs up his five tools and leaves

Prep baseball 2024: 35 Minnesota stars who the recruiters covet

Police searching for St. Paul home intruder who raped, robbed woman