The Dakota skipper is a butterfly for just two short weeks in its one-year life. A caterpillar for the rest of the year, it hunkers down under the snow in winter, preserved by an antifreeze its body produces.

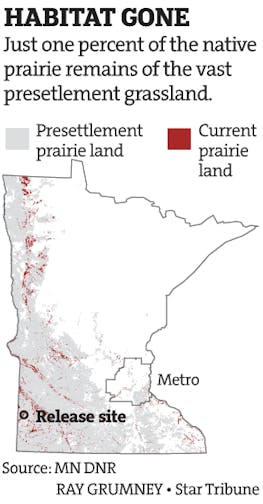

But as the tallgrass prairie disappeared across much of Minnesota, the Dakota skipper has nearly vanished. Just 1 percent of the native prairie remains, and the small brown-gold butterfly is considered threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act — one of two Minnesota butterflies on the list.

In a rescue effort, researchers at the Minnesota Zoo have been breeding Dakota skippers in captivity, and now, for the first time, the imperiled butterfly is being reintroduced into the wild.

About 100 captive-raised Dakota skippers fluttered away last week at Hole-in-the-Mountain Prairie, a nature preserve in southwestern Minnesota owned by the Nature Conservancy. Another 100 are scheduled for release there Thursday.

Tara Harris, the zoo's conservation vice president, described the milestone as "magical."

Erik Runquist, manager of the zoo's prairie butterfly conservation program, said he's nervous.

"We feel a little bit like parents sending our kids off to college," he said. "We hope they can spread their wings and fly and make something new."

Runquist estimates the butterflies have about a 50/50 chance. The team will repeat the releases for three years and monitor the population's progress.

Don't imagine a flock of doves whooshing skyward at a wedding, said zoo butterfly naturalist Cale Nordmeyer. Workers bring a white metal mesh box full of chrysalises to the prairie preserve and open it. As a butterfly creeps from the chrysalis, someone coaxes it onto a Q-tip and walks it over to the purple coneflowers in bloom nearby.

So starts a new life cycle.

Adult Dakota skippers rely heavily on the nectar of the narrow-leaved purple coneflower, the only purple coneflower native to Minnesota, and lay their eggs on tall prairie grasses such as prairie dropseed, the caterpillar's exclusive food source.

Because of the butterfly's tight connection to the prairie, they're considered canaries in the coal mine on prairie habitat. So in addition to rescuing a threatened species, the Dakota skipper project could produce new insights into the health of prairie ecology.

The butterfly's numbers collapsed as settlers plowed up vast stretches of prairie for farming, and loss of habitat remains the main driver of its decline. But the numbers crashed again about 10 to 15 years ago, when the skipper started disappearing even from prairie remnants. The zoo's team is working to figure out why.

"They tell us that something is wrong — even where the prairie remains, something else is wrong," said Harris.

They now suspect that three insecticides used on soybean aphids are culprits: chlorpyrifos, lambda-cyhalothrin and bifenthrin.

Chlorpyrifos is particularly controversial. The American Academy of Pediatrics has urged the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to take the widely used Dow Chemical product off the market because of research linking exposure to detrimental effects on developing fetuses, infants, children and pregnant women. The EPA was set to ban chlorpyrifos use on food under former President Barack Obama, but the agency recently reversed that decision.

Runquist said the Dakota skipper team has been studying the chemicals on prairie grasses and sharing its data with the EPA and the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. The next step is controlled-exposure experiments with the caterpillars.

"These little skippers that nobody has heard about are really sort of a flagship for us to learn about insects on the prairies," Runquist said.

Butterfly romance

Eggs for the Dakota skipper breeding program, which the zoo launched with several partners in 2013, were originally collected from female butterflies found on Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate tribal lands in South Dakota. The zoo has since bred multiple generations, wintering the caterpillars in a freezer and tending to pupae in small plastic cups.

Breeding isn't easy. Researchers learned you cannot stick a male and female together for results: The male Dakota skippers need to compete with others for the female's favor. In a hoop house at the zoo, a researcher sits with a clipboard, monitoring several mesh cages to spot a male sidling up alongside a female and curling his abdomen to the side — a sign they are getting in the mood.

The hope, said Marissa Ahlering, lead prairie ecologist for the Nature Conservancy in Minnesota and the Dakotas, is to re-establish a population at Hole-in-the-Mountain Prairie that can sustain itself. Then workers can repeat the project at other locations to help the species recover.

The zoo's conservation project is also working to shore up the Poweshiek skipperling, a butterfly that has disappeared from Minnesota. Researchers are waiting to receive eggs being collected in Michigan. The plan is to rear them through most of their life and then release the chrysalises back into the wild next summer in Michigan.

The prairie butterfly conservation project is a joint effort of the Minnesota Zoo, the Nature Conservancy, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Key funding comes from the lottery-financed Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund, as well as the sales-tax financed Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment, and the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Jennifer Bjorhus • 612-673-4683

Neighbors, city officials at odds over Rochester lake dam

Souhan: This is KAT's chance to prove Flip Saunders was right

The story of Hercules the cat: Rescued in 2022, Target model in 2024

Minnesota State Patrol celebrates diverse new class of troopers