"This is beautiful," Lynn Anderson was saying as she took a peek inside the lavishly appointed chamber of the Minnesota state Senate. "Wow! I wish I could work in a place like this! It sure beats working in my basement!"

Then, learning that the governor's office was just one floor below, she said, "Maybe we should go see Governor Pawlenty. He's a friend of ours! Well, he's not actually our friend. But he came to our son's funeral."

Anderson, 51, was visiting Minnesota's State Capitol for the first time Wednesday. It was a "field trip," she called it, a sad one that began the morning of Jan. 3, when two Army soldiers came to the door of her home in Jordan, Minn.

All things considered, Lynn Anderson could have lived without ever seeing the Capitol.

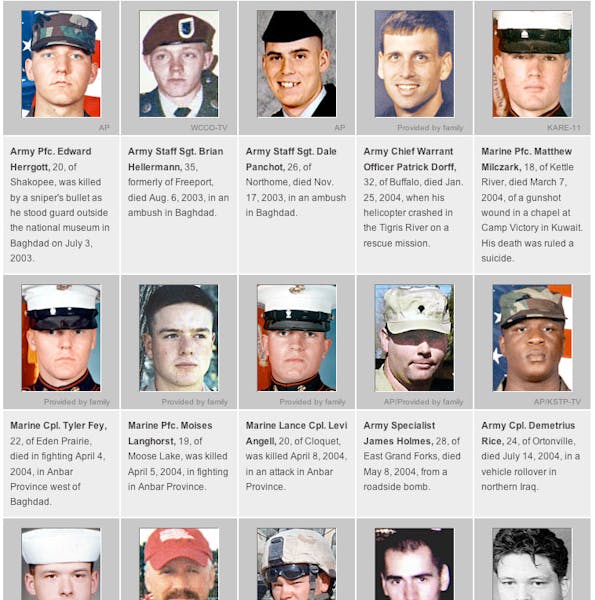

Anderson runs a daycare center in her home, tending to a dozen tykes in a lower-level room. Her husband, Keven, runs a forklift in a warehouse. On Wednesday, they came up to the Capitol for a ceremony in the Rotunda where the names of almost 4,000 Americans killed in Iraq were read out loud, including the names of about 60 fallen Minnesota soldiers.

The last name from Minnesota belonged to their son.

Joshua Anderson, a combat medic, was killed by a roadside bomb Jan. 2. The news was delivered at 7:30 the next morning. Keven was welcoming the daycare kids because Lynn was under the weather. She was in bed when Keven, cradling the fourth infant of the day, saw soldiers coming up the walk.

"Oh, no," he said. "Is it bad?" One of the soldiers started crying. "You shouldn't have let them in," Lynn says, listening to her husband's account.

But there was no holding the bad news at bay: Joshua, 24, was dead, leaving behind his wife, Hannah, and a 3-year-old daughter, Savannah. His family came to the Capitol to hear Joshua's name read to a chime that rang hundreds of times to mark the fifth anniversary of the day the war began.

People almost noticed.

I would like to tell you the Capitol of Minnesota came to a hushed halt Wednesday to observe the anniversary of a misbegotten war that has cost far too many lives to ever be worth it, but the country is not in the mood for special observances.

The Rotunda was filled with boots symbolizing the fallen, including a pair with Joshua Anderson's name and photo attached, and flowers from his grieving family. But when the names were read out, they were drowned out by the chatter and button-holing hum of the hundreds of lobbyists and legislators on the floor above. They did not cease their yammering. Not for one moment.

"When we visited Pearl Harbor, they told us to be quiet," Keven said, recounting a family trip to see the USS Arizona Memorial. "They said we should be quiet even when we were crossing the water. Here, we had all these boots on the floor representing people who died. But up there [right above the Rotunda] it seemed like it was business as usual. I felt there was a little disrespect."

Of course, there was important work going on: A cattle-herding bill was being discussed, and changes were being considered in boiler operation licensing procedures. I'm not making that up. In a country where a politician's sex life can dominate the news for days, it can be very hard to focus on a war in which thousands die.

Lynn Anderson was having trouble, listening for Josh's name. And trouble seeing.

"It's overwhelming when you're listening to so many names and, of course, you are only listening for your son's name. Some days, you can hardly make it through for yourself, let alone for all those other families. Sometimes, just saying his name sets me off. I cry all day."

For the Andersons of Jordan, the war is no abstraction. It doesn't matter to them whether anyone is for it, or against it. It's a reality that exploded their lives on the second day of the year. They want Josh's comrades back in Iraq to know they think about them. They just wrapped and sent 37 little Easter packages.

"I don't think politically about it," Lynn says, taking a long look around the gaudy governor's reception room, adorned by ornate paintings and gilt-edged carvings. "You vote a politician into office and just hope they are like a good doctor -- that he knows what he's talking about when he says you have something, and he knows what to do."

"Wow, I want to live here!" Lynn says, taking a 360-degree turn around the Reception Room with Keven and Joshua's older brother, Michael. "This could be my bedroom!"

She was joking, but maybe the Andersons should live in our beautiful State Capitol.

After all, they have paid for it.

Nick Coleman • ncoleman@startribune.com

8 months in jail for Blaine man who caused 120-mph crash hours after he was caught speeding

Daughter sues St. Paul, two officers in Yia Xiong's killing