A cop lay dying at the hands of Tim Eling.

The former Marine had botched yet another pharmacy robbery, escaping after a gunfight with police officer Richard Walton. Now, bleeding from a gunshot to the leg, Eling lay holed up at a relative's house in St. Paul, drifting in and out from a heavy dose of painkillers.

His brother-in-law walked in and dropped the morning newspaper.

"The guy's dead," he said in disgust. He left Eling to read about the trail of grief he had blazed at Mounds Park Hospital in St. Paul the night before.

Today, 29 years later, Eling still walks the corridors at the Stillwater prison. A former drug addict and a first-degree murderer, he learned last week that his life sentence has been brought to an end with an extraordinary parole decision by state Corrections Commissioner Tom Roy. Corrections officials say they cannot recall the last time a first-degree murderer of a police officer was granted a parole.

Roy's decision has triggered an emotional debate over justice and forgiveness that has quickly spread to the State Capitol. On Friday, the Legislature's top Republicans, Sen. Amy Koch and Rep. Kurt Zellers, sent a letter to Gov. Mark Dayton protesting the parole and calling for legislative hearings.

When Eling was sentenced in 1982, a prisoner sentenced to life became eligible for parole after serving 17 years. In 1993, the Legislature changed the law to require life imprisonment without parole for anyone convicted of killing a police officer. Minnesota is now among at least 30 states that require mandatory life sentences or death for anyone convicted of murdering a police officer.

The state's largest organization of police officers not only opposes parole for Eling, it says that cop killers deserve capital punishment.

"I don't think anyone who kills an officer should ever get out alive," said Dennis Flaherty, executive director of the Minnesota Police and Peace Officers Association. "Where do you draw the line, what kind of world would you be creating?"

Roy and his deputies understand the reaction, but say they believe their decision speaks to the ability of some violent criminals to transform themselves. They say Eling's conduct over the past 15 years suggests he will lead a life of service on the outside. They also note that, across several previous Corrections administrations, he had to repeatedly prove he was making changes in his life.

Try to outlast cancer

Eling, now 62, says he knows the gravity of the decision. Despite the parole, he must still complete four more years of a companion 1996 sentence for smuggling drugs while in prison. At the same time he'll try to outlast a cancer that doctors discovered several years ago.

In the course of a two-hour interview last week, Eling said he understands the disgust felt by police.

"I'd probably feel the same way," he said. "The record speaks for itself. I have not been a good person in this life."

He said he also understands the toll he inflicted on members of Walton's family.

MaryAnn Walton, 74, the officer's former wife, said last week that she accepts the judgment of state parole officials. But she added:

"I believe in transformations of heart and that people can be forgiven by God. What bothers me is I know how hard this will be on police officers. What kind of example is it going to be to have a cop killer turned loose?"

When informed on the anniversary of Walton's death that several members of the family are willing to forgive him, Eling broke down in tears.

Asked whether he deserved to be paroled after killing the Oakdale police officer, he said: "Probably not. Probably not. That's a decision that other people have to make."

Several days before his September parole hearing, he said, Commissioner Roy spoke with him privately for an hour.

"He told me he wanted to come in and look me in the eye, see who I was, face to face," Eling said. "He told me he believed people could change."

The coldest eyes

The St. Paul hospital robbery was not Eling's first.

In March 1972, detective Jim Wright and his partner pulled up to a Richfield pharmacy at 66th Street and Nicollet Avenue. Inside, a theft of prescription drugs was under way. Outside, a woman waited behind the wheel of what appeared to be the getaway car, motor running.

Two men came out, one carrying a box of drugs, the other with a nickel-plated semi-automatic pistol in his hand.

"Drop the gun! Drop the damn gun," Wright shouted.

He and his partner were face to face with Tim Eling.

"We were pleading with him to drop it -- a minute, a minute and a half," the now-retired Wright recalled. "That's a long time when you're in a standoff."

Eling finally did as ordered.

In an interrogation room soon after, Wright asked Eling what had motivated him to rob the pharmacy. Eling wouldn't say.

"He had the coldest eyes," Wright said. "He looked at me and said, 'You know, I wish I would have killed you then because I wouldn't be here now.' It gives me the willies."

Ten years later, the police officer Walton was dead and the Ramsey County attorney charged Eling with premeditated murder based in part on what Eling had told Wright years earlier.

A reason to get up

Life in prison didn't mean staying clean. Eling found himself part of a smuggling operation involving cocaine and marijuana. His urine screens kept coming back dirty and by the mid-1990s authorities went to his daughter's home to search for a possible connection.

The warden at Oak Park Heights told him during a parole review: If you're trying to make sure you never get out, you're doing a good job of it, Eling recalled.

"The warden said, 'You need to find a reason to get up in the morning. Why don't you go back to school?' Out of nowhere this thought came to my head, 'You know, I'm done with it' and I've never been high since then."

Eling became a founding member of Stillwater's Restorative Justice Program, which brings crime victims in to speak to offenders about the pain they've caused. He took up painting, and today teaches a daily art class to 22 offenders. During Mass in the prison chapel, he gives the first reading.

"You have to ask yourself, 'How do I make amends for this?' " Eling said. "If you stole something from somebody you can pay them back. If you broke something, it can be fixed. But how do you make amends for taking somebody's life?"

If he beats the cancer long enough to get out, Eling said he hopes to travel to Grand Marais and live along the North Shore, performing volunteer work and painting.

Yet he has a recurring dream in which he is stopped for a driving violation. The officer runs a license check that comes back with the murder conviction that pops up on the computer screen.

"Some things you just don't get past," he said. "If you go by just the record, holy mackerel, look at this guy here. He doesn't deserve anything. It doesn't show anything else."

Paul McEnroe • 612-673-1745

Jill Biden travels to Minnesota to campaign for Biden-Harris ticket

Want to celebrate 4/20? Here are 33 weed-themed events across Minnesota.

Legendary record store site in Minneapolis will soon house a new shop for musicheads

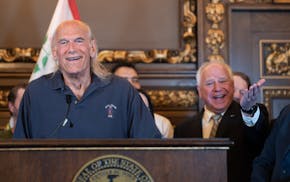

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president