It's Jan. 1, and we're awash in predictions — bold proclamations about politics and the pope, sports and celebrities. We devour and debate them, and, of course, we make our own.

When we're off the mark, we laugh it off. That's because naming the winner of this year's Oscar for best actress or declaring that the Timberwolves will make the playoffs is a low-risk wager.

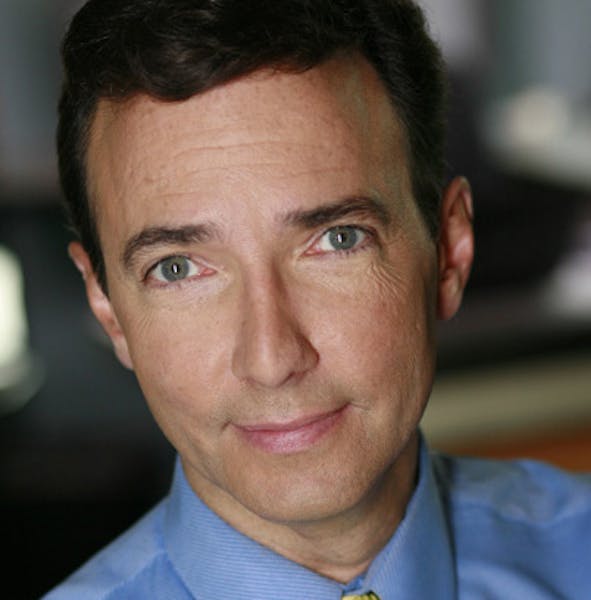

"It's an opportunity for us to play a game or demonstrate some skills where, if we're right, there's tons of benefits — we look like a genius, we feel good about ourselves," said Ryan Bremner, a University of St. Thomas social psychology professor who studies predictions. "And if we're wrong, it's OK, because the world is barely predictable."

No such luck for the pros.

With modern-day soothsayers — be they money managers, meteorologists or NFL draft seers — we're infinitely tougher, wailing mightily when a snowfall is a couple of inches more than predicted or a risky investment takes a downturn.

Most of us would admit that Yogi Berra was right: "It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future." Still, we want to know what can't completely be known, even in such complex fields as economics.

Weather forecaster Paul Douglas understands that yearning.

"Our lives are seemingly random, our personal futures ultimately unknowable. That terrifies a lot of people, the inherent unpredictability of life," said Douglas. "Just the simple act of knowing what weather may show up at our doorstep tomorrow is vaguely reassuring. It's one less potentially unpleasant surprise."

While no one has chucked tomatoes at Douglas a la Nicolas Cage's character in the movie "The Weather Man," he has felt the sting of plenty of barbs. And, for that, he blames himself and other experts who make a living by making predictions.

"We've set ourselves up for scrutiny and second-guessing," he said. "By leveraging all this gleaming technology, we've set very high expectations that are very difficult to reach every day."

Bremner, for his part, lays the blame for dashed expectations at our feet. "People dramatically underestimate the role that chance plays in events," he said.

His thoughts are echoed by Paul Dergarabedian, who projects box-office returns for a Los Angeles-based entertainment analysis company.

"You can't blame the messenger because other factors come into play," he said.

In almost all industries, professional prognosticators have more and better tools at their disposal, thanks to technology. However, most of the pros say they also rely heavily on experience, intuition and just plain hard work.

And no matter how good the tools or experienced the oracle, there's no such thing as foolproof fortunetelling.

For example, while the short-range forecast is 88 percent accurate, according to Douglas, the seven-day forecast is only about 59 percent. But when it comes to the economy, calling the shots is more complex. None of the nation's big banks came within 10 percent of predicting the S&P 500's performance in 2013.

There's also more at stake.

That's why Ross Levin of Accredited Investors strives to make decisions rather than predictions.

"A good decision will encompass a variety of outcomes," he said. "It's important not to have hubris, not to think you're going to be right when so many other factors can influence outcomes."

Surprisingly, in the soothsaying business, being right isn't everything.

It's important to examine and re-examine the process that leads to the prediction, said St. Thomas' Bremner. "Even when they're right," he said, "they might be right for the wrong reasons."

As Douglas likes to say, "predicting the future is a bright shade of gray, not black or white. You're going to have good days and bad days. Even my favorite palm-reader, sometimes she screws up."

Follow Bill on Twitter: @billward4

New Orleans Jazz Fest 2024 kicks off Thursday and The Rolling Stones to headline next week

With 'Alien' back in theaters, 'Alien: Romulus' director teases how the new film connects

Ukrainian duo heads to the Eurovision Song Contest with a message: We're still here

Here's why Harvey Weinstein's New York rape conviction was tossed and what happens next