Elaine Davis likes to tell the story of the time her grandma, a central Minnesota farm wife during Prohibition, leapt into bed and pretended to be sick when a bunch of G-men spilled out of their cars into the front yard, demanding she lead them to a moonshine stash. With the kegs safely hidden under hay mounds up in the barn, she told the kids it was a little misunderstanding about a fur taken out of season.

Wally Sentyrz, a third-generation Minneapolis grocer, remembers hearing how his then-teenage uncle would be sent out on a delivery run and not return, too wasted to drive after cash-poor customers would tip him with shots of homemade hooch.

A traveling exhibition, "American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition," opening Saturday at the Minnesota History Center, takes a national view of the only constitutional amendment ever to be repealed. But in those so-called dry years of 1920 to 1933, plenty of very wet lore was being brewed up right here in the land of 10,000 backwoods stills.

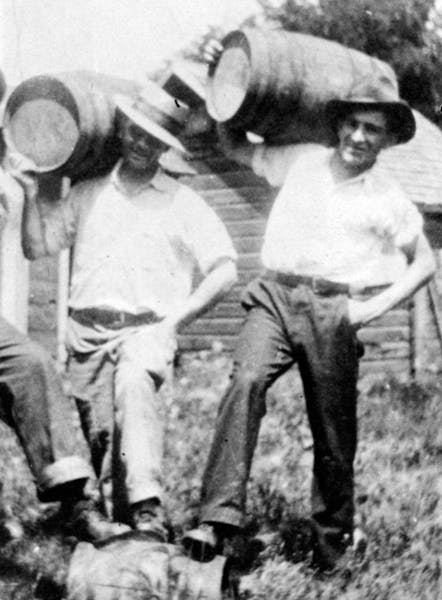

As gangsters grabbed the headlines, everyday Minnesotans quietly set up their mom-'n'-pop stills and basement speakeasies from the North Shore to northeast Minneapolis.

Shame and pride

Rural Stearns County and its primo Minnesota 13 distilled corn liquor — coveted nationwide — was a primary reason.

Davis, a business professor at St. Cloud State University, explored this aspect of her home region's heritage in her book "Minnesota 13: Stearns County's 'Wet' Wild Prohibition Days."

During her research, she found that nearly 100 percent of residents in some pockets of the county had at least one hand dipped in the illegal-alcohol trade — hundreds were booked at the county jail, and dozens spent time in the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kan.

Their descendants have a complicated shame/pride attitude, Davis said.

"The stories were not always passed down from generation to generation, because people were ashamed. I'd point to an article from 1924 about a big federal raid and say, this happened on your dad's farm, and they'd say, 'What raid?' Little old ladies would say they heard at the senior center I was trashing their families' good names. Then after the book came out, they said: 'Hey, isn't my granddad in there?' "

The ingredients in the smooth whiskey known as Minnesota 13 varied from cook to cook — some used Juicy Fruit gum to make it sweeter. It became famous nationwide and even beyond for its resemblance to Canadian Club. Farmers used ingenuity and country know-how to speed up the aging, hanging barrels from trees over bonfires, or covering them with canvas and manure to create compost-style heat.

The county's European-immigrant stock of German and Polish Catholics, Scandinavian Lutherans, Scots and Ukrainians were an ethnic mix ripe for recruitment, because they'd brought their drinking traditions with them from the Old Country.

Many of the Stearns County moonshiners were just trying to save the family farm. After World War I ended, the demand for corn and rye plummeted, and farms became worth less than they were mortgaged for.

"We think of the Depression as starting in the '30s, but it hit farmers a decade earlier," Davis said. "In those days you'd get paid the same for a calf, five dollars, as you would a gallon of liquid, so do the math. They let the barns sit empty, put up false walls and started cooking moon. A lot of the little kids helped out, pulling sacks of sugar out on sleds into the woods. Those kids are in their 90s now.

"Some of the moonshiners would disguise themselves as priests and nuns when making deliveries. At the St. Joseph train station, tiny pony kegs would be lined up labeled to be shipped out with a return address reading 'St. Benedict's College.' "

Booby hatches, false walls

Stearns County wasn't the only Minnesota locale keeping busy brewing and imbibing. Minneapolis author Sarah Stonich, whose family hailed from the Iron Range, said the Lake Vermilion mail boat used to stop at resorts with more than letters in tow.

"The local still was operated by a man called Ding-Dong," she said. "My grandfather, whose family back in Vienna had been wine merchants, grew his own grapes in Tower, and made his own wine. It often turned vinegary and was appropriated by my grandmother to be drunk as 'salad dressing.' "

In the Twin Cities, false basements with hidden booby-hatch entrances were used to store kegs and serve as after-hours speakeasies. Shaw's in northeast Minneapolis still has a trap door behind the bar that leads to a musty old underground hideout. In North St. Paul, Neumann's Bar never closed during Prohibition, serving nonalcoholic "near beer" downstairs while keeping a speakeasy going upstairs.

The basements of some private homes in northeast Minneapolis were converted into private social clubs, where the vestiges of shuffleboard courts still remain. Many homeowners kept booze secreted behind false walls. Just two years ago, a Minneapolis resident having work done on her circa-1900 Lowry Hill home uncovered a vintage cocktail lover's gold mine — 90 bottles of antique liquor, mostly unbroken.

Even after Prohibition was repealed, not all moonshiners broke the habit. The last big raid in Stearns County was in 1964, and another took place outside Faribault in the mid-1970s. But Minnesota 13 will live on: Mill City Distilling, a new company in the old Hamm's Brewery in St. Paul, is going to revive the brand — legally this time.

Kristin Tillotson • 612-673-7046

Live video of man who set himself on fire outside court proves challenging for news organizations

4/20 grew from humble roots to marijuana's high holiday