It's an old joke: Where does a 500-pound gorilla sleep? But there's a fresh answer at the Como Park Zoo and Conservatory: In a new $11 million exhibit.

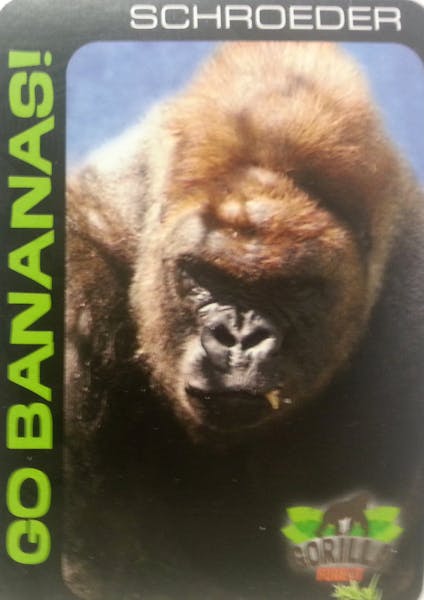

Gorilla Forest opens Thursday with six new residents — plus one familiar face, the 525-pound silverback named Schroeder. The 13,000-square-foot habitat features new interiors and two new outside areas that make up the largest all-mesh gorilla enclosure in North America.

The renovation marks another step in the evolution of this urban zoo, which dates to 1897. The old exhibit halls that consisted of little more than prison cells are gone, replaced over time by more natural environments.

"The changes in zoos have been amazing," said Michelle Furrer, director and campus manager of the zoo and conservatory. "The old zoos were just cages. Now, as we've learned more about habitat, they are much more of an immersive experience. That's better for the animals and the people."

Six new gorillas have been relocated from other zoos. They have been split into two groups with separate indoor and outdoor homes. In the "family" group, Schroeder, who has been a Como Park mainstay since 1991, has been joined by three females — Alice, Dara and Nne (pronounced Eenie) — in hopes that they eventually will mate.

The other side of the exhibit is home to what the trainers are calling the "bachelors" — Virgil, Samson and Jabir — three related males that came as a package deal.

Which raises another question: How do you ship gorillas from one zoo to another?

"FedEx," said Allison Jungheim, one of the senior zookeepers.

The gorillas rode in the same cargo planes that were carrying the doodad you bought off eBay and thingamabob you ordered from the Home Shopping Network. The only difference was that Jungheim traveled with them to make sure the animals (which were not sedated for the trip) were OK. And the fact that the zoo had to send its own truck to pick them up at the airport because there are limits to what FedEx drivers are willing to carry up to the front door.

On the shy side

The image of King Kong notwithstanding, apes can be rather timid creatures. Getting the gorillas to check out their new home was challenging.

The animals were kept in quarantine after arriving at the zoo, a standard practice. When it came time to acclimate them to the exhibit area, the keepers opened the door from the holding area — but the gorillas wouldn't budge.

"They just sat there and looked out the door," Furrer said.

The keepers have a strict rule against prodding the apes to do something that makes them uncomfortable.

"We won't do anything negative," Jungheim said. "We're working very hard on building trust with them. This [exhibit] is an unknown space to them, and they're intimidated by that."

Prodding might be out, but bribery still works. At least it did on the second attempt to coax the animals out into their new habitat. The keepers set up a gorilla buffet, consisting of banana tree leaves, bamboo and bowling-ball-sized rubber balls smeared with peanut butter.

The gorillas didn't rush out, but they did eventually succumb to the siren call of the treats. Once they were out — and had licked all the peanut butter off their fingers — they took to exploring their new digs.

The new exhibit has three times the outdoor space and more than twice the indoor area of the old one. Where the former space featured a lot of concrete, the new one lives up to its "Forest" name with an abundance of vegetation. Gone also is the moat that surrounded the old exhibit.

Gorilla Forest is designed to both challenge and calm the primates, said Mark Beauchamp, president of Philadelphia-based zoo architectural firm Clr Design. A large hill in the middle of the exhibit serves multiple purposes. It not only provides exercise when the animals climb, but also brings a sense of security. Exhibits in which the apes are surrounded by people on all sides make them nervous, he said.

"They're just like the gunslingers in the Old West who sat with their back to a corner so they could see everything that was going on in front of them," he said.

The hill also allows the apes to literally look down on us.

"We discovered that the gorillas don't like it when we're higher than they are," Jungheim said.

What's behind door No. 2?

Beauchamp's firm worked closely with the zoo's staff in designing Gorilla Forest. A crucial element was versatility for both the animals and keepers, he said.

It's "about giving the gorillas a choice," Beauchamp said. "For instance, there are two doors [from the inside areas] to the outside areas, and we want them to make choices on their own. We want them to work a little bit; we want them to think."

The gorillas likely will be around for years, if not decades. At 27, Schroeder, the oldest, is just reaching middle age, and 8-year-old Dara is the youngster of the group.

"It's not unusual for zoo gorillas to live to be 50," Jungheim said. "They live longer than their counterparts in the wild [where a typical lifespan is 30 years] because everything — food and such — is provided for them. Plus, if they get sick, they get veterinary care."

The zoo had three male gorillas until Gordy died in 2010 from myocardial fibrosis. Heart disease is the No. 1 killer of zoo gorillas, and Schroeder has been taught to let the keepers monitor his heart (which remains healthy). Togo was sent to Oklahoma City as part of the trade that brought Virgil, Samson and Jabir to St. Paul.

Despite all the work that went into the three-year project, not everything has gone according to plan. For one thing, the gorillas have been eating some of the trees that weren't intended to be nourishment. Asked what could be done about that, Jungheim conceded, "Not much."

What does a 500-pound gorilla eat? Anything it wants.

Jeff Strickler • 612-673-7392

Ashley Judd and Aloe Blacc help the White House unveil its national suicide prevention strategy

Get better sleep with these 5 tips from experts