RED LAKE, MINN. – In the Red Lake Nation, a place larger than the state of Rhode Island, there is no education gap.

"It's an education canyon," said Dan King, president of Red Lake Nation College.

While about one-third of Americans have obtained at least a bachelor's degree, only about 1.5 percent of tribal members on the Red Lake Indian Reservation hold one.

The Red Lake Band is on a mission to change that. In 2015, the band constructed a 45,000-square-foot building to house a branch of Leech Lake Tribal College. Last year, the school broke away from Leech Lake to become its own two-year institution. It's one of 36 tribal colleges in the United States and one of four in Minnesota.

The school is in the process of applying for accreditation from the Higher Learning Commission, expected in 2020. In the meantime, credits can be transferred to four-year schools under interim agreements.

King said the college's mission is to train a new generation of professionals who can become leaders in the Red Lake Nation.

"If we really want to transform our community, we have to start with education," he said. "We're about building people up, building their academic skills so they can go on to bigger and better things and then come back and help the reservation."

The college is focusing its curriculum on areas it's identified as meeting the greatest need. They include business, environmental science and liberal arts.

King is among the few tribal members with an advanced degree. He earned a master's in business administration from Harvard University and had a long career that included casino management. In 2009, he had heart surgery and stepped back from work. In 2010, tribal leaders approached him about taking over the president's job, and he's been there ever since.

Growing up in St. Paul, King said, there were "six or eight colleges within a 20-minute drive." But on the reservation, "it's a rural area, and the only education option is the tribal college."

At Red Lake, the typical student is a 29-year-old woman with children, King said. That was another reason to provide a quality education close to home. With many people here living in poverty, the demands of holding a job, going to school and coming up with money for child care and transportation prevent many people from pursuing a degree.

The college functions as an extended family, King said, offering a 12-1 student-teacher ratio and help that goes beyond the classroom, including two day care centers.

The college also is stressing tribal heritage and culture. Every student is required to take two Ojibwe language courses, and one of the day care centers is Ojibwe immersion.

The next step for the school is providing student housing. About 150 students are now enrolled, but the school has the capacity for more than 500. Building campus housing would allow tribal members from the Twin Cities or Duluth to more easily enroll.

Bryan Johnson, a 31-year-old tribal member, recently enrolled at the college. He works in auditing at the Seven Clans Casino in Thief River Falls and hopes to earn a two-year business degree and go on to Bemidji State University.

"It's a wonderful place to advance your higher education," Johnson said. "The people are awesome."

Jen Hart works as a library technician at the college as she pursues a degree in behavioral and social science. She's already making a difference.

"My kids see me going to college," she said, "and they're already talking about going to college."

John Reinan • 612-673-7402

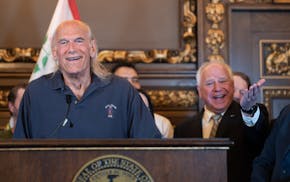

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries

St. Cloud house vies for Ugliest House in America