Minnesota law offers few protections if you are sexually assaulted when you are drunk.

You must be intoxicated or drugged

against your will.

Or you must be asleep or passed out.

How alcohol foils

rape investigations

“I remember

saying no.”

Heather Vande Kieft, 22

Graduate student

Standing outside the apartment

building

where she was raped

IN HER WORDS

Heather Vande Kieft was an 18-year-old college freshman having drinks with friends at her St. Paul apartment in 2014. She was drunk and went to bed. Her next memory is of three men she met earlier in the night entering her room. She said that as she drifted in and out of consciousness, one stole her money, another held her down and the third raped her.

“I remember they were all laughing,” she said. “I remember saying no.”

When police arrived, “You could tell they were annoyed to be there,” Vande Kieft said. A few days later, a detective called and met her at her building. Toward the end of the interview, she recalled the investigator telling her, “I bet you regret not being more careful.”

Using a photograph and surveillance video from the apartment building, police identified a suspect. His DNA matched the results from Vande Kieft’s rape exam. According to Vande Kieft’s case file, he was a suspect in an another sexual assault. His criminal record showed three convictions for domestic violence, including a 2013 case where he choked and beat a woman on the back of her head.

According to the case file, the suspect initially lied and said he had no involvement with Vande Kieft. When the investigator told him about the DNA, he said the sex was consensual.

Vande Kieft was told charges wouldn’t be filed. She was never told the suspect’s name.

“I couldn’t believe that criminals were believed over somebody that didn’t even have a speeding ticket,” she said.

St. Paul police said the investigator worked the case “incredibly hard,” and reviewed it again after the Ramsey County Attorney declined to prosecute.

“If the victim had expressed concerns with the way she was treated, the department would have responded and done everything possible to address her needs,” spokesman Mike Ernster said.

AAbout one third of the sexual assault cases examined by the Star Tribune involve victims who were drinking or using drugs. Often, the victim lacks a clear recollection of what occurred, but is adamant that she would not have consented to sex.

“How could I consent if I don’t remember anything?” said Howe.

Her best friend, Micah Desormeaux, was with her when a Roseville patrol officer arrived at Howe’s apartment.

From the start, Howe and Desormeaux said, they felt the officer did not believe Howe’s account. “He kept saying ‘I just need to be the devil’s advocate,’ ” Desormeaux recalled.

Inside the News:

Investigating Rape

A joint podcast of the Star Tribune and WCCO Radio explores this investigation.

Howe said the officer asked whether she could have met someone at the reception who then came over. He suggested that perhaps the Lyft driver helped her walk up to her apartment, she said, and asked whether she might have just taken off her clothes while asleep.

“I don’t feel like the officer thought that there was anything to investigate,” Howe said.

The police report in Howe’s case, obtained by the Star Tribune, does not contain a transcript of the interview with Howe. The officer wrote that Howe “admitted” to drinking that night.

The officer collected Howe’s bedding and clothes, then she and Desormeaux drove to the hospital for a rape exam.

Back home, Howe got an e-mail from Lyft, saying her phone had been recovered from her driver’s car. She also found a receipt from her ride home that included a photo of her driver. It was the same man she remembered standing over her.

She called the officer who took her rape report. He met the Lyft driver at a mall parking lot and retrieved the phone, but asked nothing about the alleged rape, according to the case file.

“How could I

consent if I

don’t remember

anything?”

Joanna Howe, 40

Student

Standing outside the apartment

building where she was

raped

IN HER WORDS

PProsecutors say sexual assault cases where the victim is drunk or high are the most difficult ones to prove.

One obstacle is that juries often blame victims, said Julie Germann, a former Olmsted County prosecutor.

“Juries have an expectation of what a ‘real rape’ looks like. It still looks like the bad guy jumping out of the bushes,” even though most rapes involve acquaintances, Germann said. “When you stray away from that, it’s a hurdle.”

Minnesota’s laws also make it easy for a suspect to claim that the victim agreed to have sex, even if she was blacking out, stumbling drunk or had no memory of consenting.

Ramsey County Attorney John Choi said it would be easier to win prosecutions if Minnesota law specifically said it’s illegal to have sex with a person who was too intoxicated to consent.

Current law, Choi said, requires that “you have situations where somebody is literally, physically unable to communicate that nonconsent. Do you know how narrow that is?”

At least seven states, including Wisconsin, outlaw having intercourse with a person who is too intoxicated to consent. California makes it a crime when a victim cannot consent due to “any intoxicating or anesthetic substance.” Wisconsin prohibits sexual contact “with a person who is under the influence of an intoxicant to a degree which renders that person incapable of giving consent.”

The high bar posed by Minnesota law means police and prosecutors must work intoxication cases even harder to gather evidence that would corroborate a victim’s account. Yet the belief that juries won’t convict when the victim was drunk can deter law enforcement officers from vigorously investigating those cases, Germann said, making it less likely that the rapists will be held accountable.

“When law enforcement sees alcohol, that’s often where a case ends,” said Jude Foster, a program coordinator with the Minnesota Coalition Against Sexual Assault.

That is borne out in hundreds of cases reviewed by the Star Tribune.

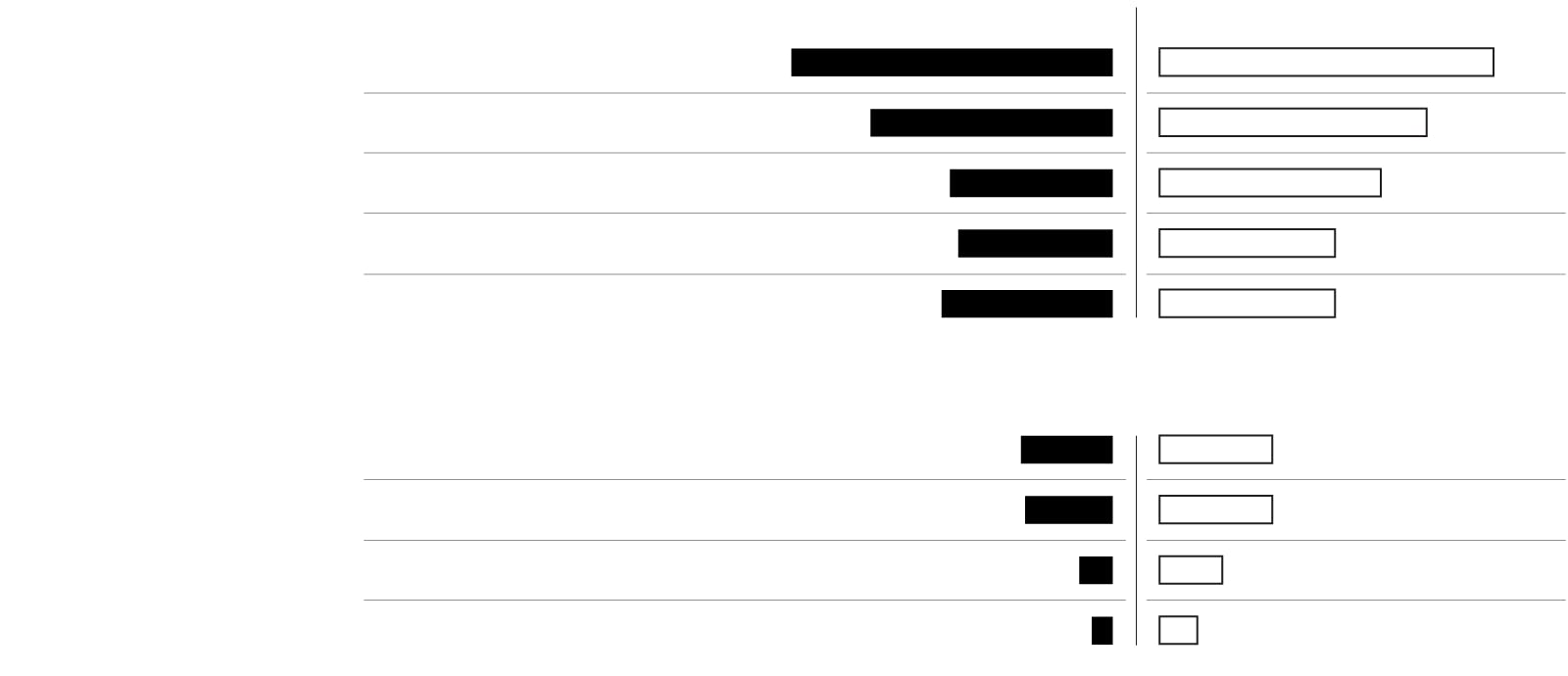

When a victim is intoxicated

Reports of sexual assault involving a victim who was intoxicated at the time of the incident are less likely to be fully investigated and prosecuted than cases with a victim who wasn’t intoxicated, according to a Star Tribune analysis of more than 1,000 police reports from around the state.

INTOXICATED VICTIM

VICTIM NOT INTOXICATED

The investigation

Law enforcement is less likely to complete basic investigative steps.

Assigned to an investigator

77%

80%

64%

58%

All evidence collected

All witnesses interviewed

39%

53%

Victim interviewed by investigator

37%

42%

Named suspect interviewed

42%

41%

0

Outcomes

A smaller share end up on prosecutors’ desks, leading to lower rates of cases being charged

and fewer convictions.

Suspect arrested

27%

22%

Sent for prosecution

27%

21%

15%

Charges filed

8%

5%

9%

Conviction

0

SOURCE: STAR TRIBUNE RESEARCH

In Waseca County, a 19-year-old woman said she called the sheriff to report that she was sexually assaulted by a friend she was staying with. The deputy asked whether she had been drinking. She said yes. He gave her a ticket for underage consumption, records show.

“I felt defeated,” the woman said.

A 19-year-old woman out drinking with friends told St. Paul police in 2015 that she vomited and drifted in and out of consciousness as she was raped by two men in the group and awoke bleeding the next day. The investigator closed the case without contacting the suspects, according to the police report, saying the men “would have reasonably believed she was acting in a consensual manner.”

A Mankato woman woke up in her bathroom, vomiting. Her last memory from the previous night at a downtown bar was accepting a drink from a stranger who said something about dropping a pill in her glass. A roommate later saw her on the couch at home, with a half-dressed man on top of her. He moved to the floor after she confronted him. When the two women found a used condom in their apartment trash, they called police.

The women provided similar descriptions of the man. So did another friend who had driven the woman and the man home from the bar.

When police met with the suspect, he denied being at the bar or with the woman. He said his roommate could vouch for him, and said he “would think about” providing a DNA sample, according to an officer’s report. Records from the 2016 case show that police never collected the suspect’s DNA, interviewed witnesses at the bar or tested the victim’s rape kit.

Weeks later, police closed the case. Public Safety Director Todd Miller said it was because the woman did not want to go forward. “Sometimes we see cases where a victim is drinking and makes a bad decision and wants to cover it up. … and [they] say, ‘Let’s report this and say it wasn’t my fault,’ ” Miller said.

Police records give no indication that the victim stopped cooperating, or that investigators believed the report was false. The Star Tribune was unable to locate the woman because data privacy laws require police to redact the names of victims in sex assault cases.

HHowe had all but given up when a Ramsey County advocate assisting her with her case said the results from her rape exam were inconclusive. She set up a meeting with the Roseville police investigator assigned to her case, Jamie Baker.

To stand any chance of getting prosecutors to charge the driver, Baker told Howe that they would have to get him to admit that he had sex with her.

At the police station, Howe said Baker posed as her and texted the driver.

“Are you interested in hooking up again?” Baker typed.

“Perhaps, what do you think?” the driver responded, according to the texts Howe showed the Star Tribune.

“Well what did we do last time?” Baker replied.

The driver texted that Howe seemed “drunk, but you were coherent.”

He wrote that they went to her apartment and he stayed for an “hour or so. We cuddled, and we had … both ways.”

Howe felt a mix of disgust but also relief. Here was the proof she would need to see him charged with a crime.

Howe said Baker told her police still needed to interview the suspect. The police report shows that Baker tried calling the driver, but his phone wasn’t accepting calls, so she wrote him a letter requesting that he contact her. About a month later, Baker made another entry in the case file: the suspect never responded.

‘I was just lost

in the dark.’

View video of women describing the experience of reporting their assaults to the authorities.

In August 2017, the file says, the Ramsey County Attorney declined to charge the driver. Howe said the prosecutor told her that because the driver texted that she was coherent and that she walked up to the apartment with him, it would be reasonable for a jury to believe that she was not physically helpless.

Howe couldn’t believe it. “There’s no way I could consent,” she said. “But because of the narrow way that laws have been interpreted in Minnesota in cases like mine, I won’t see any justice.”

Howe’s case file shows that police never interviewed witnesses from the wedding, such as the bartender, who could have described how many drinks he gave Howe. They never looked at the driver’s car to see whether Howe vomited on her way home, potentially a sign that she was too intoxicated to consent to sex. Police never tested her bedsheets for DNA. And despite having the suspect’s address, they never questioned him about Howe’s condition that night.

But Choi, the Ramsey County Attorney, said that even if police had gathered that evidence, his office likely would not have brought charges. The driver’s behavior was “absolutely outrageous,” Choi said, “but from a prosecutor’s standpoint, there’s a question as to whether it violates the law.”

Roseville Police spokeswoman Lt. Erika Scheider defended the department’s handling of Howe’s case. She noted that prosecutors never directed Baker to investigate further before declining to file charges in the case.

A Lyft spokeswoman said the driver was fired after Howe contacted the company. “We continue to have absolutely zero tolerance for the behavior described,” the company said in a statement to the Star Tribune.

CChoi said he plans to press the Legislature to change Minnesota’s law on sexual assault to specifically address intoxication and a victim’s ability to grant consent. Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman supports such a change. “It puts some of the burden on the defendant,” he said.

University of Colorado professor Aya Gruber, who studies rape laws, agreed that Minnesota’s laws need to be clarified to cover cases where the victim is intoxicated but not passed out.

Yet clearer statutes, on their own, won’t make the cases easy to prove, Gruber said. Even when someone is drunk, she said, there are still times when people can consent to sex but have no memory of it the next day.

Howe said she sometimes still struggles to fill in the blanks of what happened that night. She’s angry that she has been made to feel that she’s to blame for what happened, and troubled that the man involved probably doesn’t know he was a suspect in a criminal case.

“I was raped,” Howe said. “No matter what choices I made, I didn’t choose that.”

Read previous comments