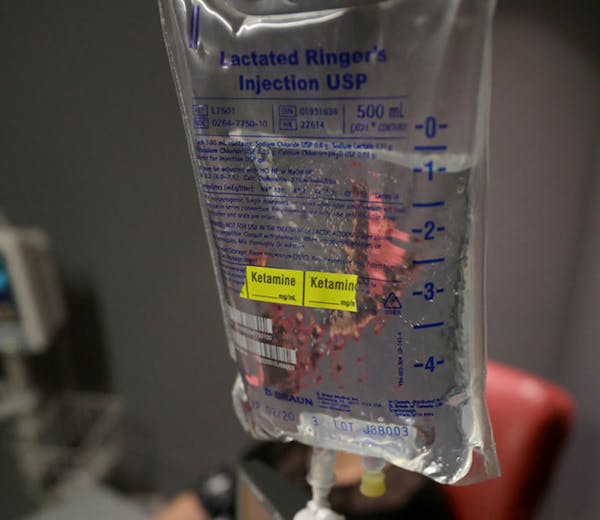

More than 60 doctors, bioethicists and academics signed onto a federal complaint this week alleging Hennepin Healthcare conducted high-risk ketamine research on more than 100 unwitting participants while ignoring ethical practices and federal safeguards.

Public Citizen, a consumer rights advocacy group, has asked the Food and Drug Administration and the Office for Human Research Protection to conduct investigations into whether the hospital complied with federal regulations during two clinical trials — one completed, the other suspended amid ethical inquiries — involving paramedics sedating people with ketamine before bringing them to the hospital.

In a statement Tuesday, Hennepin Healthcare spokesman Thomas Hayes said the hospital is aware of the Public Citizen complaint. He said the hospital's Institutional Review Board (IRB) has been accredited since 2011 by the Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs, which ensures the hospital "follows rigorous standards for ethics, quality, and protections for human research."

Hennepin Healthcare has declined to release records that document what precautions its researchers took to protect patients.

The Public Citizen complaint alleges that researchers put these patients at unnecessarily high risk by changing their standard treatment to fit with the needs of the clinical trials. It also accuses the hospital's IRB of failing to fulfill its duty by allowing these researchers to enroll members of the public into the study without consent.

"The subjects deserve an apology for that failure," said Dr. Michael Carome, director of Public Citizen's Health Research Group. "And this could just be the tip of the iceberg. What other research is ongoing at this institution where the IRB has just completely failed to do its job?"

These allegations add to mounting questions and independent investigations over the hospital's use of ketamine on patients without prior consent. Last month, Hennepin Healthcare said it would suspend all clinical studies that featured this "waiver of consent."

In several public appearances, the hospital's chief medical officer, Dr. William Heegaard, has defended the research practices as ethical and in line with federal guidelines.

However, when the Star Tribune and others filed requests for the records that would show how they complied with these standards, lawyers for the hospital said they cannot be released until investigations into the research have been completed.

"At the conclusion of these reviews, we expect that the Institutional Review Board data will be public and we also look forward to sharing conclusions of the independent outside reviews," Heegaard said in an e-mail to the Star Tribune.

Carl Elliott, a University of Minnesota bioethics professor who signed the Public Citizen complaints, also requested these records and expressed frustration over the hospital's decision to classify them as private after leadership repeatedly said they did nothing wrong. "If the leaders of Hennepin Healthcare genuinely believe these studies were conducted ethically, then they should be happy to make these documents public," said Elliott. "The fact that they're refusing to let anyone see the documents suggests they are hiding something."

Scrutiny over the ketamine research comes after the Minneapolis police oversight office questioned whether officers inappropriately urged paramedics to sedate people with ketamine, in some cases resulting in serious medical complications. A draft of the office's report, obtained by the Star Tribune, also questioned whether the drive to recruit patients for research led paramedics to use the drug when it wasn't medically necessary. A final version of the report will be made available to the public later this week.

In previous interviews, researchers for the hospital said ketamine is a crucial tool for paramedics dealing with severely agitated and volatile patients. They said the study does not increase the use of ketamine, and researchers only study the data to measure how it compares to other sedatives in the field. "Anytime that we interact with EMS about this, we emphasize to them, crystal clear: In no way is the study ever to increase the number of sedations," Dr. Jon Cole, an emergency physician and toxicologist at Hennepin Healthcare, said in an interview in June. "We want to observe normal, usual sedation practices."

The Public Citizen complaint challenges that assertion. It alleges that the phase of the study changed the treatment given by the paramedics. One study compared ketamine to another sedative, haloperidol. For the first three months, the paramedics were told to use haloperidol when treating severe agitation. For the second phase, they used ketamine, and "haloperidol was removed from all ambulances."

"Thus, the clinical trial protocol dictated whether a particular subject with prehospital agitation would receive ketamine or haloperidol and precluded use of any other medication," according to the complaint.

And the research found that haloperidol, while not as fast-acting, was considerably safer. "Notably, subjects receiving ketamine were 10 times more likely to have breathing problems that required placing a breathing tube in the subjects' tracheas than those receiving haloperidol," according to Public Citizen.

The complaint also questions whether, in order to comply with the study, paramedics used sedatives when it was not medically necessary. The more recent study included sedating people with ketamine who did not meet the highest level of agitation — scoring "plus-two" on a scale in which "plus-four" is considered most severe.

"You should only use a potentially life-threatening drug in a life-threatening situation," Carome said. "For these trials, where they lower the threshold for using these drugs, it appears they do that for research purposes."

Ex-Hennepin sheriff paid for drunk-driving damages with workers' comp

Souhan: This is KAT's chance to prove Flip Saunders was right