It's no surprise that choreographer Bill T. Jones chose to develop and perform "Story/Time" at Walker Art Center. He clearly has an affinity for Minneapolis, raving about the latest restaurants he and his manager/life partner Bjorn Amelan have discovered.

Over a long, leisurely breakfast at Le Meridien Chambers Hotel, he wistfully recalled hanging out at the Saloon in his younger days, when few cities were as open to the gay population as Minneapolis was.

But "Story/Time" also works here because it's a "small" project. In New York or Los Angeles, there may be pressure to do something spectacular, like another musical or a follow-up to his huge Chicago production of "Fondly Do We Hope ... Fervently Do We Pray," a work that challenged audiences to rethink their beliefs about Abraham Lincoln.

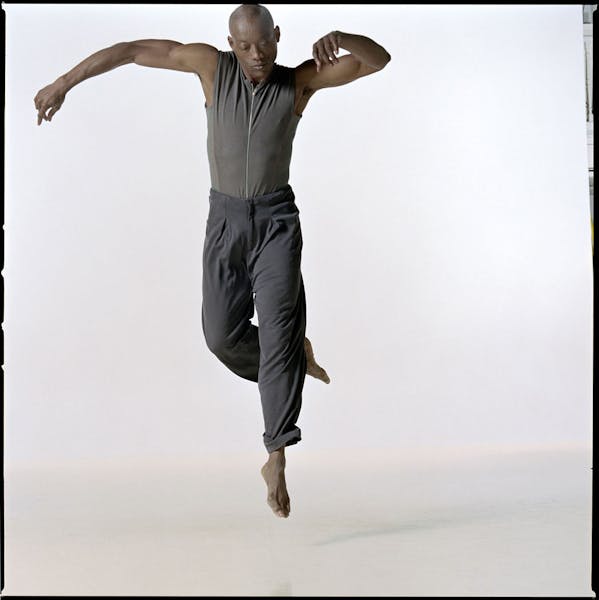

"Story/Time" is the opposite. There's little decor onstage and even less lighting. Jones will select about 70 one-minute stories out of 130 he's written, a different selection each night determined by chance, and read them. His dancers perform highly physical numbers while he sits. Very. Very. Still.

It goes against the grain of what the dance world expects from him these days. In other words, it's vintage Jones -- and local audiences are, once again, along for the ride.

"There are so many changes in life, so to have continuity at a place for 30 years is great," Jones said. "It's a wonderful thing."

Philip Bither, Walker's senior curator of performing arts, crystallized Jones' relationship with the Twin Cities audience by telling an anecdote from a 1998 concert at Northrop Auditorium. During a Q&A session afterward, a shy, nervous gentleman asked for the meaning behind a particular scene.

"Let me ask you," Jones replied. "What did you see?"

The man proceeded to give a poetic description involving a flock of birds fluttering through the sky as the sun broke out.

"Then that's what it was," Jones said.

On stage, a fierce energy

In the past five years, Jones has won Tony Awards for his work on "Spring Awakening" and "Fela!" on Broadway. He also was feted in Washington, D.C., with a Kennedy Center honor. But he still refers to Minneapolis as his "home away from home."

When he was 27, the Walker selected him to educate arts-starved neighborhoods. His first commissioned piece for the museum was 1981's "Break the Glass," in which Jones and a Chinese artist were backed by a troupe of white dancers, reflecting the isolation so many minorities in the arts world were feeling at the time. The climax: Jones ripping up a piece of paper with such intensity that it was borderline violent.

"It was wonderfully exciting and angry," said Nigel Redden, then the Walker's performing arts curator and now director of the Lincoln Center Festival in New York. "He didn't go around smashing up dressing rooms, but onstage he was not afraid to be fierce."

Jones' frustrations built after dancer Arnie Zane, his longtime partner both on and off the stage, died of AIDS in 1988.

Shortly after his loss, Jones was in Paris and ran into Redden's successor, John Killacky. The two retreated to a café, where Jones shared his vision of a piece that would include 52 nude dancers, the number being a reference to the card games he would play with Zane in the hospital. Killacky promised his support and helped recruit the University of Minnesota and Minnesota Dance Alliance as partners.

The result: The 1990 premiere of "The Promised Land," which became the last section of Jones' groundbreaking five-part work "The Last Supper at Uncle Tom's Cabin."

Critics saw it as a piece utterly devoid of sentimentality, brimming with intensity and a desire to overcome adversity. It eventually toured the world and was seen on PBS' "Great Performances."

But it wouldn't be a Jones masterpiece if it also didn't come with controversy.

During rehearsals, then-University of Minnesota President Nils Hasselmo instructed students in the cast to keep their clothes on. They obeyed -- for a while. Before the premiere, Jones advised the young dancers to "follow their heart." By the time the curtain went down, so went their clothes.

Protests followed during the world tour, but there was barely a peep in the Twin Cities about the nudity.

"The community was used to coming together in a collaborative way," said Killacky, who is now executive director for the Flynn Center of the Performing Arts in Vermont. "There was this generosity of spirit, of saying 'Let's try something.'"

Guthrie debut in 1994

Jones continued to thrive in Minneapolis -- making his directorial debut on a major stage with 1994's "Dream on Monkey Mountain" at the Guthrie, premiering 2001's "The Table Project" in the shared lobby between the Guthrie and the Walker, teaming up in 2003 with Cassandra Wilson in the Sculpture Garden -- providing local arts lovers an opportunity to track an artist over more than three decades and watch him blossom into an international star.

"If you honor something, or someone resonates with you, you're awfully glad to see him get wider recognition and develop along the way," said arts patron Sage Cowles, who along with her husband, John, went au naturel in "The Promised Land." "That's never easy, especially in the dance world."

The Walker has been able to maintain a relationship with Jones because it's one of the few institutions dedicated solely to modern dance and it believes in long-term commitments to artists.

"Time is invaluable, and the Walker got that a long time ago," Jones said. "Artists need time and an intelligent audience base. Minneapolis has been spectacular about that."

- Follow Justin on Twitter: @nealjustin

Minnesota Sports Hall of Fame: A class-by-class list of all members

This retired journalist changed professional wrestling from Mankato