David Carr was flying high over the Minnesota State Fair -- literally and figuratively -- as he snorted cocaine in the Sky Ride en route to an interview with then-U.S. Sen. Rudy Boschwitz. That's what Sarah Janecek, a Boschwitz aide at the time and a longtime Carr friend, recalled from that day more than two decades ago as she accompanied Carr.

"Rudy was completely oblivious," said Janecek.

Carr, for the record, doesn't remember exactly what he did that day. But during the 1980s and 1990s, he gave many Minnesotans a ride that most will never forget -- leaving behind stories, smiles and bruises as they watched his roller-coaster life as a writer, drug abuser, confidant to the powerful and in-your-face media personality.

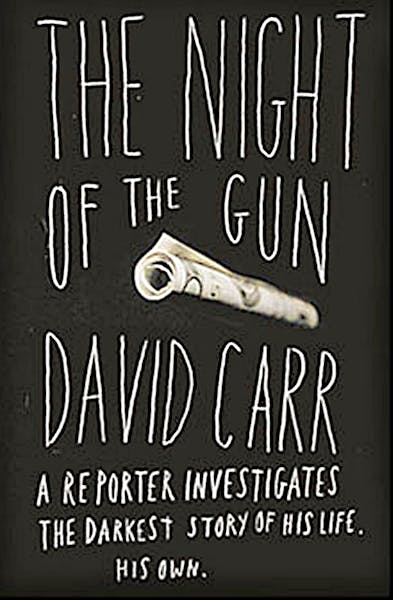

His new memoir, "The Night of the Gun," is drawing raves and opening old wounds. Excerpted by the New York Times, where Carr now works as a media columnist and roving reporter, it is largely set in the Twin Cities, from its back alleys to the State Capitol, and invokes every big local story of that era, from the gang murder of Christine Kreitz to the fall of banker Deil Gustafson.

Parts of his account are disputed by friends like former Minneapolis police chief Tony Bouza, an unabashed Carr fan who nonetheless said the writer probably imagined some of what happened, a result of drug-induced paranoia.

Carr, feisty as ever, is ready to take on anyone who might wonder how he could get the story straight while bleeding from the nose during an interview with Gov. Rudy Perpich after having snorted coke. He is also quick to tear into the question of whether, during his downward spiral and personal and professional comeback, he ever took advantage of the willingness of people to give him multiple second chances.

"I can't tell you how strongly I disagree with that level of cynicism that drives that question," he said.

For many, including Carr, the task of telling his story has always included sorting out the contradictions. While he acknowledged that sometimes he "didn't do a good job" of keeping his professional and private lives separate, he defended his ability to work as a reporter while high.

"Why don't you go back and read the clip?" he said. "I think I won a [journalism] award" for the story that the Perpich interview yielded. "I did things differently," he added.

Carr did do things differently, and has his regrets. In the book, he describes leaving his two infant daughters alone in a car, in the cold, as he went to buy drugs. "How long had it been, really?" he wrote. "It had not been ten minutes tops. Ten minutes times ten, probably, if not more. Hours not minutes."

His biggest champions in Minnesota, and there are many, prefer to dwell on the good times, and there were many of those, too.

"I love the kind of character he was," said David Nimmer, the former Minneapolis newspaper and TV personality whose own struggles with alcohol gave them common ground. Nimmer visited Carr in treatment and took his twin girls Christmas shopping. "He walked off the pages of a Damon Runyon short story," he said.

Like Nimmer, Minneapolis Mayor R.T. Rybak said he did not live the details of Carr's darkest periods. Rybak said Carr coaxed him to become the publisher of the Twin Cities Reader, the now-defunct alternative weekly, when Carr was its editor in the mid-1990s.

"I saw him as a real hero who had overcome his demons," Rybak said. "It was a great time and, for a while, better than I thought we could ever get to."

Rybak had less to say about an incident in the book when Carr publicly referred to a female Reader staffer as having a "nice rack." Carr acknowledged he was "pulled into the publisher's office and told that I made some of the women in the office uncomfortable." Rybak declined to talk of the episode, other than to say "I applaud David's honesty."

Minnesota congressman Jim Ramstad, a recovering alcoholic who met Carr at a recovery meeting, also is a fan. "I deeply admire his courage," he said of the book.

Not everyone is as kind. "I couldn't understand why I was the only one who felt relieved when he was gone," said Cherie Parker, who worked briefly at the Reader and said "there was a ton" of hero worship of Carr at the paper. Parker said she cried when Carr harshly criticized her first story, and she will never forget her job interview: "He shouted at me, 'When I was your age, I was selling coke.' I'm, like, 'O-kaaay.' "

Rose Farley, another Reader reporter whom Carr hired, said he was a good editor and mentor, and someone who "knew how power worked in Minneapolis." He was also a mesmerizing storyteller who was not bashful about his past.

Farley recalled Carr taking his staff to dinner and holding forth about the time he left his girls in the car.

"It's such a horrible thing -- you can't believe he's sitting there telling us," she said. "He was entertaining you with it."

For all the nasty stories, Michael Welch, another longtime friend, said it was Carr's personality that kept people coming back for more. Carr, he said, is "a guy who has always had a pretty good-sized bag of charm to be able to deploy. People want to be with him."

Reconstructing his past

In his book, Carr reprints rejection letters he received over the years -- from the New Yorker, Playboy and Esquire, among others -- as he tried to sell his story. He said he decided to try again when he needed tuition money for his daughters Erin and Meagan, "independent, brilliant young women" who are now 20 and attending college.

Throughout the book, Carr said it was concern for his daughters that pushed him to straighten out. "Meagan and I, we're smarter because you are our dad," Erin tells him in the book. "We learned a lot from you."

Armed with a tape recorder, he revisited old friends in Minneapolis -- and some who were less than friends -- to reconstruct a past he admits he did not fully remember. The result is a eye-opening book filled with characters like Tony the Hat, a "full-on gangster" who marveled that Carr could do so much cocaine and still be fat, and comedian Tom Arnold, who met future wife Roseanne Barr when Carr was present (and whom Carr helped get out of legal trouble).

The book also mentions some who felt betrayed. Before Carr was hired as Reader editor, longtime Twin Cities writer David Brauer confided to Carr that he was applying. But Carr didn't tell him he was angling for the same job.

"He was lying in the weeds," said Brauer, who said he had watched Carr "use and betray" others, but never him. He eventually forgave Carr. "I still love the guy. I'm still rooting for him. I'm thrilled with his talent." But, he added, "I don't know if I've ever met a better manipulator."

Longtime friend Janecek introduced Carr to his current wife, Jill, with whom he has an 11-year-old daughter. She recalled being "incredibly shocked" by their nuptials. In the book, Carr described it as "a massive wedding: cops and robbers, judges and crooks, politicos and fixers." But in Janecek's view, "the whole wedding was about David. It was all about David having gotten to where he was."

False memories?

Carr's unreliable memory has given others pause. Former Reader reporter Farley wondered how he could recall details of leaving his two daughters in the car but have no memory of entering treatment at one point.

"Really, you don't remember a whole episode of going into a treatment program?" she said.

One story in the book is flatly denied by two of the players. Carr discusses his reporting on the Minneapolis police decoy unit, then led by David Niebur. Carr did not identify Niebur by name, but described the unit as led by a "tough cop" who himself was in treatment. Carr said he called the unit's leader, wondering why he had not given up his gun as state law required for anyone entering treatment.

A few days later, "my phone rang and [he] said -- I am recalling this decades later -- 'You know, I've been asking around and your life is not without blemish. You'd better watch your step.' For weeks afterward, I would drive somewhere and see the van that the decoy unit drove, in my rear-view. I eventually had a very uncomfortable conversation with the police chief complaining that some of his officers were following me around. He made them stop."

Both Bouza and Niebur, who have long since left the police department, said it never happened -- and wondered whether a paranoid Carr simply imagined it.

"I read that and I thought, 'I don't think so, David,'" said Bouza, who nonetheless described Carr as someone who "writes the truth" and said he continues to follow Carr's career at the New York Times.

"Understandably, under the drug-addled mentality, I think he suffered from a fair amount of paranoia," said Bouza.

Bob Olander, a Hennepin County social services official who helped Carr get state-funded treatment, said his problems were frighteningly real. "I never sensed for a moment that the game was about a hustle," said Olander. He said Carr had been through a "pretty heavy coke thing and a booze deal" and was having a "moral struggle" over how to raise his daughters while still traversing his own personal mine field.

A story yet to be finished

Some friends wonder: How much of that is in Carr's rear-view mirror, even as he reaches new professional heights? In an interview late last month, he talked of "coming up on three years sober" -- he started drinking again in 2002, then quit after a DWI arrest -- and being less of a jerk these days, though "probably not much less."

Twin Cities businessman Dave Cowley, who has known Carr since the 1970s, said he heard him talk recently about meeting megastars Mick Jagger, Gwyneth Paltrow and Paul McCartney in his role as New York Times columnist. It is a fast crowd for someone trying to conquer his own demons, Cowley said.

"I worry about him," he said. Carr's story is "a gripping story but, you know, it never has an end."

Mike Kaszuba • 612-673-4388

In heated western Minn. GOP congressional primary, outsiders challenging incumbent

Minnesota Sports Hall of Fame: A class-by-class list of all members

This retired journalist changed professional wrestling from Mankato