CAMBRIDGE, MASS.

Junot Díaz leans his shoulder against a crammed bookshelf in the living room of his apartment near Harvard Square, propping one argyle-socked foot against the other. He looks slighter, wiser and wearier than Yunior, the alter ego who stars in many of Díaz's short stories.

Still recovering from surgery in June for the spinal stenosis that gave him excruciating back pain, he now spends some of his time in a new leather recliner bought for this purpose.

At the moment, though, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer of "The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao" is standing, the better to expound on love.

"To be truly in love we must be found out," he said. "The one place where you really have to practice transparency is, obviously, with that person, because without that there is no love. You have to lay down your shield. That's why so many dudes are bad at it. Because we're told vulnerability is the antithesis of masculinity. And you wonder why so many of us have trouble."

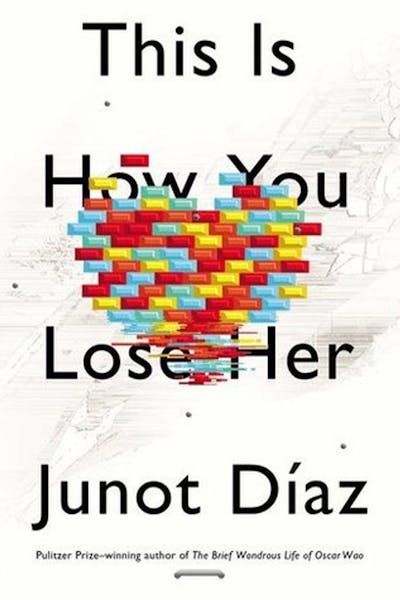

Girl problems are something Yunior -- who, like Díaz, grew up hardscrabble in a working-class Dominican immigrant family -- has plenty of in the author's new story collection, "This Is How You Lose Her" (Riverhead, $27), a followup to his first book, 1996's "Drown." Díaz comes to town Sept. 18 as the first guest in this season's Talking Volumes series at the Fitzgerald Theater in St. Paul.

Díaz's conversation is literate/street, like his writing -- words like "fulgurating" and "atavistic" pop up between Spanish slang, F-bombs and the adjective "dope." He's a word nerd who once delivered pool tables for a living, a kid from a macho 'hood who favors geek-chic specs. He's down with the traditions of his people from the "DR" (Dominican Republic), and he's an American-as-"Star Wars" sci-fi fanboy. He's a cultural amalgam, the kind of American who most accurately represents what being an American now means.

And it's impossible, he says, to separate the influence each piece of the pie has on his attitudes and writing.

"To paraphrase Maxine Hong Kingston, how much of it is your culture, how much of it is just you, and how much your crazy family? There's no filtering system to sift through that. But the legacy of my Dominican-ness involves wrestling with masculinity, patriarchy, a history of dictatorship and immigration, the particular but almost invisible membrane that makes up a culture."

'Comic and heartbreaking'

Díaz's writing is the opposite of lofty, but it struts across the page too boldly to be called something as lame as "down-to-earth."

Díaz, 43, has appeared frequently in the New Yorker. The magazine's fiction editor, Deborah Treisman, calls his voice "unlike any I've come across, with its combination of the lyrical and the vernacular, of English and Spanish, of speech rhythms and internal reflection. It has a kind of unstoppable energy, an inexorable drive forward -- even when his stories move in difficult or tragic directions, the language jumps off the page in ways that can be simultaneously comic and heartbreaking."

Reading any of his work is like getting a bonus lesson in Dominican street slang -- some of it, like sucia, derogatory to women. The word literally means "dirty girl," but the severity of its intent varies.

"It's a dicey thing," Díaz said. "Yunior uses sucia in a lot of different contexts -- some are dismissive, some are wistful. But none of them are useful."

The last story in "This Is How You Lose Her" is likely to strike Díaz followers as particularly autobiographical. Yunior is teaching at a college, he develops back problems, his friends are worried about him dwelling on his breakup. Díaz said that while similar events transpired in his own life, the similarity stops there: "I threw in a lot of personal touches, but Yunior's suffering and his reaction to his suffering is uniquely his own," he said.

The "her" of the title bears some similarity to Díaz's former fiancée, lawyer Elizabeth de Léon, with whom he went through a volatile breakup several years ago. His current partner is Marjorie Liu, a writer of paranormal romance and comic books who is responsible for the only feminine touches in the living room, a few orchids.

Close-knit and proud

After he won the Pulitzer for "Oscar Wao" in 2007, Díaz was presented with a key to the city, and Jan. 25 was declared Junot Díaz Day in Boston, where he has taught writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for 10 years. Still, he's no stop-him-on-the-street celebrity, there or in New York City, where he keeps an apartment, in Harlem's Hamilton Heights.

"My relative secrecy has allowed me to maintain a normal life," Díaz said. "That's the best thing about being a writer: You can be anonymous."

Depending on the neighborhood, of course. If you ever see Díaz in a wrinkled shirt, it won't be in a Dominican part of town.

"I'd only do that if I wanted my entire neighborhood to run out and lend me an iron," he said. "I once had a girlfriend walk out of the house with her hair natural and someone threw a comb at her."

Among Dominicans, Díaz said, "It's a survival strategy. You get up in each other's business at the same degree as your intimacy. Communities like ours have to be close-knit to survive."

Following the family's emigration from Santo Domingo to join his father when Díaz was 6, he grew up the middle of five children near a huge landfill in Parlin, N.J. (also the young Jon Bon Jovi's stomping grounds). His mother and two sisters still live in New Jersey, his two brothers in California. His brother Rafa, whose fictional version succumbs to cancer in one of the most touching segments of the new book, pulled through in real life.

"I grew up in a world with a lot of pride, Old Testament pride. The Rafa character has these Abrahamic tendencies. If you wrong him, he will pay you back. Yunior is more New Testament. He is capable of forgiving, even though it's hard for him. Rafa would consider that a weakness."

As a kid, Díaz spent a lot of time at the library, soaking up books. He became a big sci-fi fan. Despite coming from an environment in which higher education was the exception, he worked his way through an English degree from Rutgers in 1992, followed by an MFA from Cornell three years later.

He was working as a temp photocopier at Pfizer when he got the call that "Drown" had been sold. After its critical and popular success, Díaz was hit with the "writer of promise" mantle, which can feel more like a choke collar to any newbie about to embark on a sophomore effort, and being America's best-known Dominican writer, thus bearing the responsibility of translating his culture to the rest of us.

But "those external impositions don't even get a place at the table compared to my internal pressures," he said, describing his "ruthless, exacting" self-editing process of one page forward, two pages tossed.

He did go through some terrifying writers' blocks, but eventually Díaz published his novel. The story of a fat Dominican loser, his troubled family and his quest for the girl of his dreams, "The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao" also is a crash course in Dominican history, including the atrocities and eccentricities of its former dictator, Rafael Trujillo, not exactly a household name in the United States.

"Young Dominicans here don't know anything about him, either," Díaz said. "An ignorance of history is the great commonality of the American people."

The novel knocked critics' socks off. They called it "astoundingly great," "highly flammable," "a hell of a book" that "doesn't care about categories."

"This Is How You Lose Her" was to have been a quick followup to "Drown." Instead it was 15 years in the making. "I do wonder whether I've thrown out some very good years," he said. "I'd like to be able to change that, but you can only work the way you work."

Compassion, even for cheaters

The Boston area is home to several Dominican restaurants. The most prominent is Merengue, which serves such homestyle fare as chicken with parsley sauce and mofongo, a dense, tasty dish of mashed plantains and garlic. Díaz, a habitué, is godfather to one of owner Hector Piña's children, and a picture of him with Piña's wife, Nivia, hangs on the wall.

"He's a little bit shy," Piña said of his friend. "When I introduce him as a Pulitzer winner, he's not comfortable with the attention. He's really a low-profile guy who doesn't know how famous he is."

Piña also sheds light on the Dominican cultural mores that get Yunior into trouble and lead to his ultimate heartbreak. Historically, he said, straying has been the norm for Dominican men.

"They were always going off to find something else. When I was growing up, my grandpa had a wife and a querida, a mistress, and kids with both. Everybody knew. Women were accustomed. Everybody was happy, and I don't really know how they did it."

Yunior's running inner commentary is often contradictory. The same guy who says "old sluts are the hardest habit to ditch" later pines that "the half-life of love is forever." His future, including whether he will change his pattern of sleeping around, is open-ended, leaving the reader to imagine him as ultimately happy, or not.

"He begins as a guy for whom cheating is like getting a pencil mark out of a shirt; you erase it and move on," Díaz said. "At the end, he has to confront the reality of the consequences of infidelity. We aren't often asked as readers to be sympathetic to masculinity. But if any of us cracked our brains open and poured out all the truth, who wouldn't find some deeply troubling things? I think we should practice compassion toward flawed people, because we all are."

Díaz has had a decade-long friendship with Minneapolis writer David Mura, whom he dubbed "the jedi master who showed me the way," in his acknowledgements for "Oscar Wao." They room together at the annual Voices of Our Nations writers conference, which Díaz helped found.

"Junot addresses an audience that is immigrant and literate like him," Mura said. "He doesn't translate the Spanish or explain his references. But still his writing grabs the reader immediately. It's this subtle blending of standard literary language with American colloquialisms and Dominican Spanish slang onto a seamless whole. That takes incredible skill."

Díaz said Mura once gave him some advice that still echoes.

"That sometimes you've got to become the person you need to become before writing the book you want to write," he said. "The desire and the talent are not always enough, sometimes you have to change as a human being."

Has he?

"I became more compassionate towards myself and by extension other people. I did change. But I fear not enough."

Kristin Tillotson • 612-673-7046