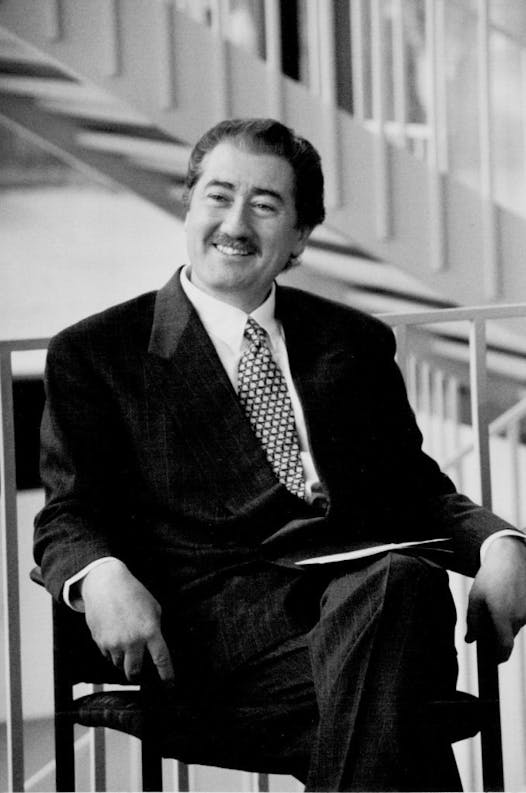

For a man whose early hope was simply to reach adulthood, Joe Dowling has built an impressive career. Not since Tyrone Guthrie founded the company that would bear his name has someone become more associated with the Guthrie Theater, one of the nation's acclaimed regional theaters. The journey Dowling took to become its 20-year leader, reinventing the theater in the process, was unlikely and unexpected.

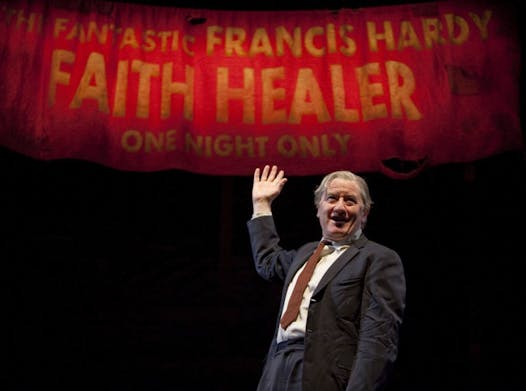

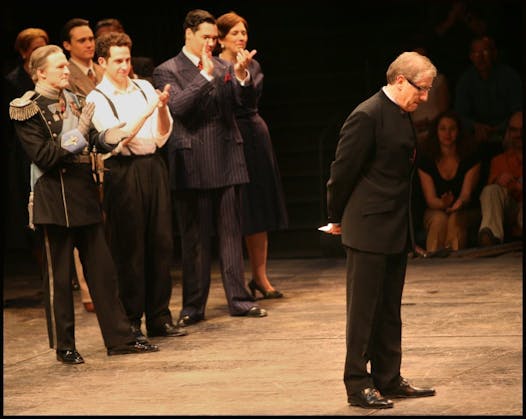

Dowling's production of Sean O'Casey's "Juno and the Paycock," which opens Friday, will be the last of the 50-plus shows he has directed, and caps a spate of successful shows by him, including "The Crucible" and "A Midsummer Night's Dream." His mark on the theater extends beyond the stage, though. He reinvigorated the company financially, nursemaided a BFA program with the University of Minnesota, brought prominent playwrights to Minnesota and, most significantly, moved the Guthrie to its perch on the Mississippi River in downtown Minneapolis.

Irv Weiser, a lifetime board member, called Dowling "a transformational leader" who inspired the board to raise money for the new theater, which changed a neighborhood and the city skyline. Still, Weiser said, Dowling's artistic output was equally important.

"What Joe has accomplished with the work — with bringing Arthur Miller and Tony Kushner here, with bringing in great talent from all across the country, with caring for and educating a whole new generation of actors and theater professionals, with being a good steward of the funds and trust of the public — all of this has vaulted the Guthrie onto another plane," Weiser said.

The Guthrie's 200-seat flexible-space studio is named in his honor, as is a fellowship to Tyrone Guthrie's Irish estate turned artist retreat. Dowling became a celebrated man of the stage in spite, or perhaps because, of family misfortune.

When he was 8, his father, economist Brendan "Ben" Dowling, died of cancer. That loss left his mother, four brothers and him, the middle child, bereft. It also cast the family into poverty. Widow Jane Dowling, his mum, returned to the civil service job she'd left 15 years earlier, at the same pay level, barely sufficient to meet their needs.

The family often fretted about eviction, even as Jane tried to shield her children from the truth of their situation.

"We were not desperately poor; there were others worse off," Dowling said. "But we knew it was precariousness." Those circumstances sharpened in him and his brothers a drive to succeed. (All did, especially in business.)

In those childhood days, his dreams were not of acting, directing or running a theater like the Guthrie.

"We were a family far removed from those kinds of ambitions when I was a kid," he said. "My ambition was simply to grow up."

By his own admission, Dowling was a seriously bashful boy — and still is a shy adult, although those who have seen him work a room or command a stage may find that hard to imagine. Luckily for him, he found theater. His grandmother enrolled him in a drama class, which he took to like a Shakespearean sprite to wings.

"They say acting is the shy person's revenge," he said. "Theater, from that point on, was fixed in my head. I knew that's where I wanted to be, and I was fortunate enough to be able to do it. I've never done anything else in my life, and I've never regretted it."

Theatrical wunderkind

Dowling, born in 1948, quickly shone in his new pursuit. He won poetry-recital competitions and, at 16, the Shakespeare Cup for his recitation of Hamlet's soliloquy, which he easily breaks into in his spacious office overlooking the Stone Arch Bridge: "Oh, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!"

In 1967, he enrolled at the Abbey School of Acting, which was attached to Ireland's national theater (and where he met his future wife, journalist Siobhan Cleary). A year later, he joined the Abbey company and, in short order, founded the Young Abbey, an outreach program. Dowling left the Abbey to run companies, gaining managerial experience and learning the business side of theater.

In 1978, at age 29, he returned to the Abbey as artistic director, the youngest leader in the history of a company founded in 1904. It was there that he honed his style and cemented his reputation for paying close attention to line readings and making plays accessible.

"You put on a show not for yourself or critics, but for the audience to come," he said. "At the end of the day, they're the ones who determine if you're standing."

His comments about critics are familiar, as Dowling has described his relationship with the news media as "toxic." A sensitive man with an elephant memory, he lives in a tightly controlled world and doesn't read reviews of his shows unless he is told that it's OK to do so by his staff.

He demands fierce loyalty from those in his employ (and he, in turn, is fiercely loyal to them). Still, those he perceives to be disloyal can be given the silent treatment or punished in other ways. Outspoken actor Stephen Pelinski, who spoke his mind about Dowling to a reporter, was cast as the ass Bottom in "A Midsummer Night's Dream" in 2008, one of his last shows at the theater.

Dowling, by turns charming and pugnacious, left the Abbey in 1985 after a rancorous disagreement with the board of directors. A year later, he became head of the Gaiety Theatre, where he founded the Gaiety School of Acting, Ireland's national theater training school. Colin Farrell and Olivia Wilde were among its students.

The Gaiety gig was a good and secure one for a married father of two, but he left to become a freelance director. The gamble paid off when in 1988 his production of "Juno" opened on Broadway for a three-week run as part of a festival. New York Times critic Frank Rich called it "alive at every level — as boisterous comedy, as wrenching tragedy, as blistering social commentary."

A man who worked the room

Such rave reviews got Dowling noticed across the country. Years later, when the Guthrie began looking for a successor to Garland Wright, the reserved Texan known for his visually arresting productions and lack of fiscal discipline, Dowling's name rose to the top of the list.

Guthrie board members Weiser and Margaret Wurtele, who led the search committee, knew what they wanted: someone with strong artistry who also was committed to the management side and to civic and cultural engagement.

"When Irv and I were in Dublin on our last interview of Joe, we were standing outside a restaurant waiting for him to come out," Wurtele said. "He took a while so we went back in, and there he was, working the tables, saying 'hi' to everyone. Irv and I looked at each other and said, 'Omigod, that kind of engagement is really going to help the Guthrie.' "

Dowling first saw the move as iffy. He had not stayed in any job for more than seven years. He told Siobhan, a prominent TV broadcaster about to sacrifice her career, that the family would be in the Twin Cities for three years.

But as he drew in audiences with his populist productions of shows such as "A Midsummer Night's Dream," Chekhov's "Three Sisters" and Gilbert and Sullivan's "The Pirates of Penzance," the public and the board became smitten with him.

In all, more than 6 million tickets were sold during the Dowling era, including international collaborations and shows made with diverse local theaters such as Penumbra, Mixed Blood and Pillsbury House. A high-water mark was the Tony Kushner festival, anchored by Marcela Lorca's landmark production of "Caroline, or Change," which starred Greta Oglesby as the title character.

"Joe is a sweet man who is renowned for caring about actors," said Oglesby, who earned ovations for her star turn. "I'm eternally grateful to him because he trusted me on his big stage and I did my best to deliver."

He also focused on high-quality actor training, which had been a recurring passion ever since he saw the caliber of acting at Abbey. With the University of Minnesota, he supported the late Ken Washington as that theater teacher and director set up a conservatory BFA theater training program whose graduates include "Frozen" and Broadway star Santino Fontana.

"Without Joe's vision to create the training program and without his taking a chance on me and hiring me for a full season as a young graduate, I don't know what I'd be doing right now," said Fontana, who memorably played Hamlet at the old Guthrie space.

Dowling's popularity and charm would become key selling points when the Guthrie sought to build its Jean Nouvel-designed three-stage complex on the river with state funding. Gov. Jesse Ventura twice vetoed bonding money for the Guthrie and was overridden once. Gov. Tim Pawlenty signed legislation that gave the Guthrie $25 million toward the $125 million project.

As could be expected during a long tenure, Dowling spearheaded many changes at the Guthrie. The first is that he did away with the acting company.

When he came, "the youngest member was 35," he said. "I thought, 'There goes 'Romeo and Juliet.' "

Instead of sharing power with a co-equal managing director, as is common in the world of nonprofit theaters, Dowling was a CEO-style director, leaving him with blind spots — notably a three-stage celebration of plays by Christopher Hampton in 2013. The festival fared poorly at the box office, and the Guthrie ended in the red that year for the only time during Dowling's tenure.

Diversity question still stings

Dowling also came in for criticism when he announced preliminary plans for the symbolically important 50th anniversary season, a slate that was dominated by white male playwrights and directors.

Issues of gender and cultural equity had improved dramatically at the Guthrie under Dowling. He had hired more artists of color and more white female playwrights and directors than all of his predecessors combined. But his defense often sounded tone-deaf.

Dowling said he found it ironic that "at the time when everyone was screaming about the Guthrie not being diverse, what was on our stages? We had James Baldwin's 'The Amen Corner' on the main stage and in the studio, Carlyle Brown's 'Have You Now or Have You Ever Been.' I kept thinking, 'What's wrong with this picture?' "

But the criticisms stung, and his response today still betrays anger.

"I'm not going to take any shit from people that say we haven't been as strong [on diversity] over the years," he said. "I've heard it argued that the Guthrie claims its diversity on the back of other companies. Well, we fund those companies, we subsidize those companies. I look to someone like Lou Bellamy who says the way we worked with them was a new paradigm for how Penumbra can work with an organization like the Guthrie."

The cultural-equity issue is one of the challenges Dwling leaves for his successor, Joe Haj, who takes the helm July 1. Haj has been meeting regularly with Dowling, in sharp contrast to the single 15-minute chat Dowling had with his predecessor, Wright.

Dowling will take a vacation, then move to Manhattan this summer. He intends to continue directing — staging "Othello" in Ireland next year — and will teach and write. He is working with Guthrie dramaturge Jo Holcomb on a memoir-style book about building the new Guthrie.

He'll be back in Minnesota often, he said. His son, Web designer Ronan Dowling, and daughter-in-law, Caitlin, live in Apple Valley with their two small children. Also, Minneapolis is where he took his oath of U.S. citizenship, learned to golf ("I'm terrible at it, so I say it's a terrible game," he said) and went to Twins, Timberwolves and Vikings games.

"Twenty years — you form bonds you don't break," he said. "But it's time for me to move on and the theater to move on."

Rohan Preston • 612-673-4390

Live video of man who set himself on fire outside court proves challenging for news organizations

4/20 grew from humble roots to marijuana's high holiday