When Isabel Allende starts a new book, she always begins writing on Jan. 8. She's superstitious that way, because it's an important literary anniversary. On that day in 1981, she wrote a letter to her dying grandfather. The letter blossomed into her first novel, "The House of the Spirits." It became an international bestseller that won an award for novel of the year in her native Chile.

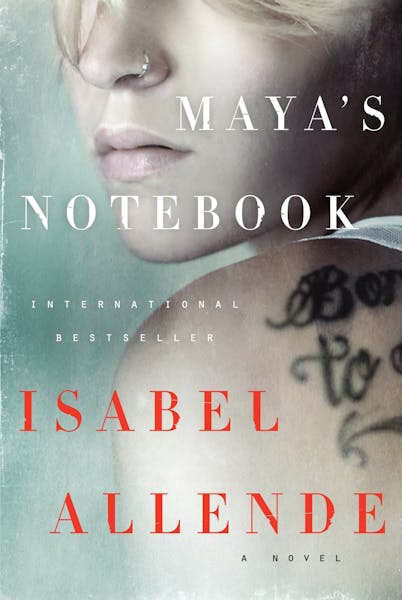

More than 30 years later, Allende has amassed many more honors and written her 18th book, a contemporary novel titled "Maya's Notebook." She appears May 8 at the Fitzgerald Theater in St. Paul as part of the Talking Volumes author series.

Allende, a young-looking 70, lives with her second husband, lawyer Willie Gordon, in San Rafael, Calif., near San Francisco. Her son Nicolas lives nearby with his family.

Allende's life reads like that of one of her heroines — perhaps, as theirs are, tinged with a bit of magical realism. She grew up with a box seat to one of the most tumultuous periods of South American history.

She was born in Peru, where her father was Chilean ambassador, into a family with powerful connections. Her father's cousin Salvador Allende became president of Chile and died under long-debated circumstances during the 1973 coup in that country. Her parents separated when she was 3, and she spent her childhood in Chile, Bolivia and Lebanon after her mother married another diplomat.

In the 1960s, Allende herself worked as a diplomat and had two children with her first husband, Miguel Frias. After the coup in Chile, she went into exile in Venezuela, where she became a journalist and teacher. She was nearly 50 before she sat down to write the fateful letter that would launch her to the status of a fiction superstar.

Allende married Gordon in 1987 and moved to California. She became a U.S. citizen 16 years later. Her American years have brought some heartbreak amid the joy. Her beloved daughter, Paula, died in 1992 after a medication error left her in a permanent coma, and she and Gordon have since lost two of his children to drug and alcohol addiction, one of them recently.

"Maya's Notebook" is a departure for Allende, whose novels usually take place in the past. Its title character is a Berkeley teen who, after the death of her beloved grandfather Popo, spirals down into a world of drugs, prostitution and theft, with a girl posse calling themselves the vampires. At 19, on the run from a variety of dangerous pursuers, she retreats to an island off the coast of Chile and writes her story, aided in her recovery by an eccentric group of fellow islanders.

More than any other Allende character to date, Maya represents a modern coming-of-age — abandoned by her mother, given a solid foundation by the grandparents who raised her, she still succumbs to the temptations of a seedy underworld life, fulfilling the worst fears of those who love her before relying on that same foundation to crawl out of the gutter.

Q: Who or what inspired the character of Maya?

A: Maya is like a summary of all my grandchildren. I wrote the book at a time when all of them, three biological and three others through marriage, were in their teens. I saw them exposed to so many dangers — drugs, violence, pornography — things that weren't all around me when I was growing up. None of them have these kinds of problems, but it's a sadly common thing for young people to lose their way with drugs and never recover.

Q: You recently lost your adult stepson to an overdose. Has that made it hard to talk about the part drugs play in "Maya's Notebook"?

A: The timing has been very eerie, very tragic. All three of my stepchildren became addicts, and now two are dead. So much of that journey into hell that can come with drugs and alcohol, the petty theft, the homelessness, I have seen it in my stepchildren.

Q: The relationship between grandparents and grandchildren is an important, recurring theme for you. Why?

A: I grew up in the house of my grandfather, a strong male figure who was strict, severe, no touching or cuddling. But he gave me many life skills, especially discipline. Whenever I feel flaky or lazy or start doubting my capacity, the voice of my grandfather comes into my mind.

Q: You once wrote that your approach to truth is "if it hasn't happened, it certainly will." Is that still your philosophy?

A: Yes, and it scares me. When I wrote "Island Beneath the Sea," about the creation of Haiti as a country, the book came out the same week the earthquake there happened. Sometimes I feel I am provoking these things.

Q: You've written 18 books in 30 years, but surely you must have felt unfocused or blocked at some points in such a prolific career.

A: After my daughter Paula died, I wrote a memoir about her, and then felt blocked for three years. I would sit at the computer and nothing would come. Then I remembered my journalist training, and I wrote a nonfiction book as far away from death as possible, about lust and gluttony. Traveling, getting out of my comfort zone, also helps.

Q: Is it true you were once fired for making the heroines of English-language romance novels more independent when you translated them into Spanish?

A: Yes, it was a freelance job. The women were always a little stupid and at the end a man would always have to save them. That's boring. I tried to make them better, more interesting people.

Q: Do you prefer writing in Spanish or English?

A: Fiction happens in the belly, so I'd rather just let it all out in Spanish. But now that I've lived in an English-speaking country for 25 years, I write Spanish like my husband speaks it. I need a dictionary.

Q: Tell us about your husband, Willie Gordon, a San Francisco lawyer who is now also a writer. How did you fall in love?

A: I thought maybe it would be a weeklong affair. He said he liked tall blondes, and the first time he took me to his house the garage floor was covered in dog poop. I was 45, and I fell in love like a teenager. We're very happy, but circumstances have often been hard.

Q: What makes your relationship work?

A: We really like each other and have important things in common — our politics, neither of us is religious, we both like dogs and the same movies. Our domestic life is comfortable. It's a dance we are always doing, being together without stepping on each other's toes.

Q: You have sold more than 57 million books, translated into 27 languages, and won many prestigious awards. Yet some critics, particularly in your homeland, have been harsh about your writing. What's your theory?

A: If I was a man I probably would have had respect earlier for my work, especially in Latin America. But I think what bothers a lot of people is that my books are bestsellers. That's wrong; it's a big underestimation of readers.

Q: So what's it like being 70?

A: In my case aging doesn't mean retiring. Getting older is more of an expansion than a contraction for me, a letting go, eliminating the people you don't like from your life. Getting rid of clutter leaves space for new things.

Q: You sure don't look 70.

A: I look much better in pictures. You can't see I'm so short that I'm almost invisible. I can't wear heels, but now everybody's wearing platforms and stilettos. I was just at a cocktail party and everyone's shrimp fell on my head.

Q: You have written that you used to write lies in your journals, that you were an "unbearable arrogant brat." What did you mean?

A: I was self-centered, creating a reality that suited me, having that feeling that you can change the world with excesses of imagination. When I met my husband I fell in love with a project. Husbands are like countries, I thought, such wonderful material for improvement. That's arrogance. Before my stepchildren I hadn't seen addiction up close before. Thinking that it results from a lack of love or discipline? That's ignorance.

Kristin Tillotson • 612-673-7046

This retired journalist changed professional wrestling from Mankato

All-Metro Sports Awards: Here are the 2023 winners