It has been 50 years -- Dec. 19, 1961, to be exact -- since the wreckers took their first swing at the fabled Metropolitan Building, but the wounds to the city's psyche and skyline still seem fresh. If only we could travel back in time 121 years, to 1890, when 8,000 people, including the upper reaches of Minneapolis society, gathered to celebrate the opening of what was originally called the Northwestern Guaranty Loan Building.

It was billed, correctly, as the largest, most lavish office building in the Northwest, and it was a study in contrasts, with its ponderous stone exterior masking a breathtaking interior atrium. Sunlight, pouring in from an enormous skylight, shimmered through green glass-block floors and bathed the soaring space in an aquatic, cathedral-like glow.

"The most profound experience we had was the privilege of walking into the Metropolitan Building and witnessing one of the most exciting spaces we had ever seen," is how the editors of Progressive Architecture magazine, aghast at the prospect of the building's impending destruction, described the Met's light court in 1960.

The Met's demolition is considered by some to have paved the way for a more preservation-conscious Twin Cities. If not for the outcry that followed its unnecessary destruction, would beloved architectural treasures -- Landmark Center in St. Paul, Butler Square in Minneapolis -- still be standing?

Ahead of its time

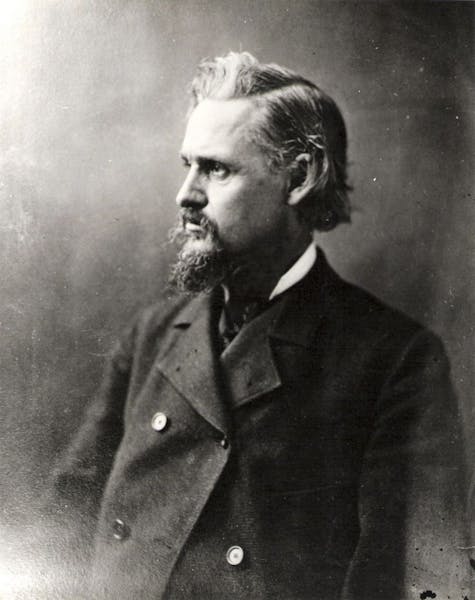

Stylistically, the Metropolitan was a trendsetter. The light court's filigreed grillwork presaged the Art Nouveau movement by a decade. Six manually operated birdcage-style elevators and their machinery were open for all to see, a delicate form-follows-function solution. And the sweetness and light of that thrilling 11-story atrium, which architect E. Townsend Mix gift-wrapped -- for maximum contrast -- in a hulking, rough-hewn facade, was ahead of architecture's Brutalist movement by several generations.

The first three floors boasted 4-foot-thick exterior walls of green New Hampshire granite. Red Lake Superior sandstone, quarried near Houghton, Mich., trimmed the upper nine floors, where the exterior walls slimmed to 2 feet. Hallways were lined with 7-foot-high Italian marble wainscoting and doors and windows were trimmed in a veritable forest of irreplaceable old-growth oak.

The open-air rooftop garden and observation tower were tourism magnets for more than a quarter-century. Gibbs' Restaurant initially occupied much of the 12th floor, where 50 cents bought a multi-course dinner served on Haviland china by tuxedo-clad waiters. Its owner was Jasper Gibbs, an African-American, and the Minneapolis Tribune described the rooms of his sumptuous restaurant as "marvels of comfort, elegance and convenience," the "largest, finest restaurant west of Chicago." (The space later housed Pillsbury's baking labs).

The city of Minneapolis -- in 1890, it was 23 years old, with a population of 165,000 -- had its first piece of world-class architecture. For several decades thereafter, the building was the pride of the city, and 308 2nd Av. S. was its most prestigious business address. Along with owner Louis Menage's various interests, original tenants included forerunners to the Soo Line Railroad, Wells Fargo and Pillsbury. It quickly became the state's No. 1 rental property for high-powered attorneys, who made use of the 10th floor's 10,000-volume law library.

The Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. took title in 1905, and put its name on the building. Over the next few decades, as the city's business core began to migrate away from the river, the Met's Class A status waned. By the 1930s, the Met was "a barn, half-empty," recalled a janitor in a 1941 newspaper story.

The building was nearly converted to a parking garage during the Depression, but wartime demand for office space reversed its declining fortunes. Locals H.D. Michael and Melvin Hansen bought it from Metropolitan Life in 1946, for $450,000. At the time it was almost completely occupied, primarily by government agencies; the former top-floor restaurant was a sea of gray U.S. Army desks.

Wrong place, wrong time

Postwar downtown Minneapolis was ailing, and a dramatic gesture was thought to be the only cure. The plan? Demolish the city's skid row -- 22 blocks, a third of the business district -- and start over with a clean slate. It was called the Gateway, and the Met, perched near the district's southeastern edge, initially made the preservation cut. But opinions reversed, and the Met's owners found their landmark on the chopping block.

The city's powerful Housing and Redevelopment Authority (HRA) laid out its case for the building's destruction in a September 1961 Minneapolis Star op/ed piece, written by general counsel Ben Palmer. The bottom line: It was old, it was ugly, it was in the way, and it had to go. End of argument. Although they put up a good fight, the building's owners and many admirers didn't stand a chance.

What's odd is how the HRA's public- sector leadership seemed obsessed with the economic viability of a privately owned venture. Given the opportunity, the HRA argued, the Met's tenants would flee from its dowdiness, even though the building was 98 percent occupied in 1958 and generated $300,000 a year in revenues for its owners. Still, the long process of condemnation started in May 1959.

The HRA and its director, Robert Jorvig, enlisted the formidable influence of the city's fire marshal, who initially declared the building a firetrap. Shortly before demolition, he revised his opinion, endorsing the building's preservation and considerably cutting his cost estimate of a fire-safety retrofit. But by then it was too late.

No complaint was too small for Palmer to forge into ammunition. The Met wouldn't fit in among the Gateway's trendy plazas, he argued, since the building had no setback from the street. It lacked air conditioning, which Palmer experienced firsthand, since the agency's offices were located on the Met's 12th floor. Ironically, architect Robert Cerny -- a Gateway mastermind who received several plum commissions in the district -- also officed at the Met, "while plotting its destruction," noted Hansen.

"The HRA is not destroying the building; the Metropolitan Building has lived its economic life and cannot survive without a transfusion," Cerny explained in a 1959 letter to the Minneapolis Tribune.

While describing the building's exterior as "a monstrosity in the eyes of most observers," Palmer noted that Sheraton, IBM and other top-tier tenants would steer clear of the Gateway if their modern structures sat adjacent to something so old-fashioned. The CEOs of both businesses issued contrary statements shortly thereafter.

"Thirty years from now the buildings in the renewal area will be 30 years old, while this one would be 100 years old and showing it." Palmer wrote, a bitter irony given the brief lifespan of many of the Gateway's throwaway structures. (IBM was razed in 1985 after just 22 years, and the 27-year-old Sheraton went down in 1990.)

The beginning of the end

A last-ditch effort, involving the city buying the building as a City Hall annex, didn't gain a lot of traction from an indifferent City Council.

The building's remaining tenants were evicted on Halloween 1961. Seven weeks later, on an overcast Tuesday morning, sledgehammers hit sandstone trim on the building's roof, although the literally rock-solid Met didn't go without putting up a fight. The last bit of debris was hauled away on Sept. 23, 1962, five expensive months behind schedule. "A victim of the peculiar American idea that motion is the same thing as progress," read Minneapolis Star columnist Don Morrison's eulogy.

The HRA's post-demolition plan didn't go any further than selling the land -- for $32,000, about $240,000 in 2011 dollars -- and it promptly became, yes, a parking lot. For nearly 20 years. "It's one of the most expensive parking lots in the history of Minneapolis," Hansen later observed to his granddaugher.

Parts of the building were salvaged. The intricate grillwork disappeared into homes and businesses. Many of the massive stone blocks were laid to rest in a Delano landfill. Some of that granite recently has been resurrected and repurposed into a sculpture-park project in south Minneapolis.

A relentlessly banal office building filled the parking lot in 1980, a dose of the suburban blahs plopped onto the streets of downtown Minneapolis. It may be standing on the site of the mighty Metropolitan, but it never replaced it. Nothing could.

Minnesota Sports Hall of Fame: A class-by-class list of all members

This retired journalist changed professional wrestling from Mankato