Long before a Minneapolis police "flash-bang" grenade burned Rickia Russell during a botched drug raid last year, the devices had sparked unintentional fires and caused injuries and deaths, even among officers trained to use them.

The $1 million settlement awarded last week to Russell by the Minneapolis City Council follows lawsuits and payouts for people injured or killed by the devices in California, Michigan, New York and other states.

The devices came into widespread use in the 1980s, and law enforcement agencies say they help save lives during drug raids and similar high-risk operations. But watchdog groups and defense attorneys say they're a menace.

"These things are dangerous," said Clay Conrad, a lawyer in Houston who has handled several cases involving flash-bang grenades. "If you were to toss one at a cop, you would be indicted for attempted murder."

Often used by SWAT teams to disorient suspects with deafening booms and bright lights, the flash-bangs, once activated, can burn at almost 4,900 degrees, the city of Minneapolis' training manual indicates.

The grenades are considered basic equipment for almost all of the country's 4,000 tactical teams, said Don Whitson, a police sergeant in Fort Collins, Colo., and chairman of the Less Lethal section for the National Tactical Officers Association.

During the training sessions that he leads nationwide, Whitson presents slide shows of officer and civilian injuries that resulted from flash-bang use.

"The incidences in injury is very low compared to the number of times they are deployed," said Whitson. "They're not toys and they should be respected."

Last week, Minneapolis officials called Russell's injuries an accident and said they were reviewing the incident. In a statement, City Attorney Susan Segal said that since the raid, "the manufacturer of the [device] has changed the design to reduce the risk that the device will roll after being deployed."

Police declined to comment Monday, saying they would have more information Tuesday.

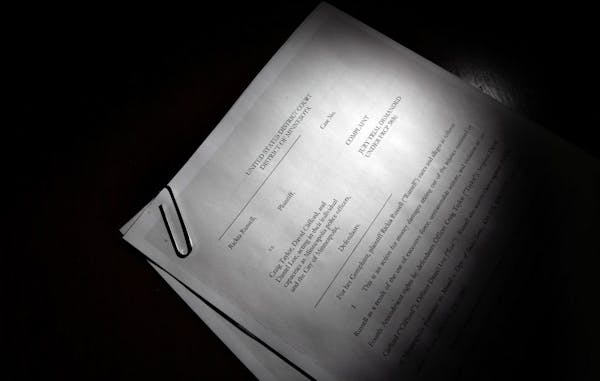

Russell suffered third-degree burns to her legs in February 2010 when city police knocked down the door of her boyfriend's apartment and set off a flash-bang.

While officers handcuffed Russell, her legs caught fire, nearly burning to the bone.

Police had a search warrant for a drug dealer, narcotics and weapons, but found nothing.

The Minneapolis police training manual indicates the devices should be used only in life-threatening situations. The manual requires that all officers wear eye and ear protection, gloves and protective clothing and have a working fire extinguisher at the ready.

It was unclear if the 18-officer team had an extinguisher. According to the complaint, officers smothered the flames on Russell's legs with soiled dish towels.

The settlement wasn't the first flash-bang mishap for the city. In 1989, two people died of smoke inhalation in a North Side apartment after a device ignited a fire during a drug raid. The incident prompted a temporary halt in the use of flash-bang grenades, and led to an undisclosed settlement and tighter oversight of the police.

Reasonable action?

Since the devices debuted in Los Angeles in the early 1980s, their use by police officers has led to at least seven deaths nationwide, including a Charlotte SWAT team member killed in January while he secured the equipment in the trunk of his squad car, according to a 2003 University of Georgia study and subsequent press reports.

"It's nonlethal only in the sense that it's not intended to inflict death," said Donald E. Wilkes Jr., a University of Georgia law professor who did the study.

"Police ... using bombs as a search and seizure technique is completely inappropriate," Wilkes said. "They use them so recklessly."

Last fall, the city of Oakland paid $1.2 million to settle a lawsuit filed by a woman who, like Russell, suffered third-degree burns when a flash-bang grenade exploded near her during a raid. The incident left her permanently disfigured.

In January, Rogelio "Roger" Serrato was consumed by flames and died after SWAT officers tossed a flash-bang into a home in Greenfield, Calif. The police agency involved maintains that a drug suspect was inside the house at the time.

Serrato's family is being represented in a civil suit by Michael Haddad, an Oakland lawyer and president of the National Police Accountability Project's board of directors. Haddad compares the growth in flash-bang deployments to the rise in Tasers. Deaths and serious injuries have to occur before more departments restrict use of the devices and improve training, he said.

The New York City Police Department, the nation's largest, stopped using the grenades in 2007 after a woman died of a heart attack during a drug raid several years earlier, the New York Times reported last year.

Charles "Sid" Heal, a retired Los Angeles County sheriff's department commander and National Tactical Officers Association member, credits the devices with saving the lives of suspects who would have otherwise been shot during a raid. The flash-bangs often give officers a six- to eight-second window to subdue suspects, he said, because it overwhelms their senses.

"They couldn't bring the guns to bear," Heal said. "[The flash-bang grenades] can be godsends."

But the opportunity for abuse remains, Heal said.

"They work so well that the novice tends to overuse it," Heal said. "It's the same with a Taser or pepper spray."

Corey Mitchell • 612-673-4491

Trail section at one of Minnesota's most iconic spots closing for rehab

Will 'shotgun only' zone for deer in southern Minnesota be abolished?

Four Minnesotans catch salmonella in outbreak linked to basil sold at Trader Joe's