WILLMAR, MINN. – Marshall Brinton owns a 15,000-square-foot building on the east side of town, just off the railroad tracks, where he once ran a business concocting vaccines for poultry farmers.

Now he's dreaming that someone will grow marijuana there.

The retired veterinarian mothballed the property after his back gave out. He's been unable to sell the place, but he thinks it could be ideal for growing marijuana and extracting the oil for medicine.

It has a big boiler, lab equipment and ventilation hoods jutting from the back wall. "I have almost all the equipment needed," he said.

Brinton and hundreds of other Minnesotans are swarming at medical marijuana, an industry state lawmakers created this spring when they legalized cannabis oil for people with some types of cancer, epilepsy and other illnesses.

Almost all of these prospectors will give up or fail. Marijuana will be an odd, tightly regulated market — controlled by two companies, expensive to enter, legally complicated and initially limited in its rewards. The law creates a marijuana duopoly, and investors hope the two firms that win permits will dominate the market — even if competitors eventually are allowed in.

"I don't think that anybody's looking at the current opportunity as an amazing business opportunity," said Kris Krane, co-founder of 4Front Advisors, a cannabis industry consulting firm in Arizona. "There's going to be a first-mover advantage. If you're granted one of these permits early on, you're in. You're in the system, you're going to have the ability to lobby to change and expand the system."

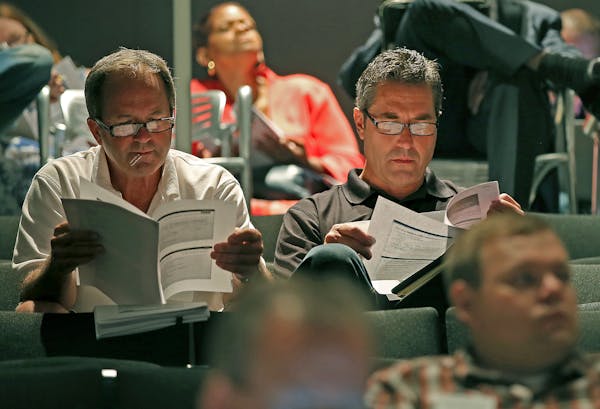

Flower and vegetable growers are thinking of cultivating cannabis. Investors are quietly hiring consultants from other states. Lawyers are trying to position themselves as experts. A meeting last week for interested people drew about 200 people who are studying whether they can make money on pot.

The rules on how to grow marijuana, extract the oil, package it and sell it are still in draft form, with much work ahead for rule makers at the Department of Health. But in less than two months the department expects to receive applications from would-be growers and sellers.

The program will favor well connected, deep-pocketed coalitions with expertise in law, health care and agriculture. They'll need to afford pharmacists, warehouses or greenhouses, laboratories, third-party lab testing and storefronts for dispensaries.

"I think it will reframe some people's thinking, about thinking this is some dude in a patchouli shop," said Manny Munson-Regala, assistant health commissioner for the state. "That's the part about this that's been really interesting, is to see the evolution from counterculture to mainstream medicine. We're not there all the way, but that transition has been fascinating."

'The long view'

The pool of patients with diseases severe and painful enough to qualify for medical marijuana under current law is about 5,000, according to the state's conservative estimate. Those people will be able to buy cannabis pills or oil, but not marijuana in plant form, from one of two companies that receive permits.

Trent Woloveck, chief operating officer of the Denver-based American Cannabis Co., estimates the average patient will spend about $126 per month on marijuana. If none of the 5,000 qualifying patients buys pot on the black market, that's $7.6 million in total annual revenue for two companies to fight over.

Experts disagree on the specific numbers, but start-up costs will be in the multimillions. Woloveck says a business could start with $2.1 million in initial investment. Brendan Kennedy, CEO of Privateer Holdings, a marijuana private equity firm, said the cost should be closer to $5 million. Others put the number higher.

Each of the two permitted companies in Minnesota would eventually set up four dispensaries, and a pharmacist would be required to hand the product to a patient. Add in the costs of water and energy, 15 to 20 employees, and building rents, and the barriers to entry are high.

"It's expensive to do this well and to do it right," said Kennedy, whose firm has a $22 million marijuana business portfolio and just raised another $50 million. "In some of the states, it's so tightly regulated and there's so much animosity that it doesn't seem like a great business opportunity."

Minnesota will seem like a better opportunity if the law is relaxed. The Department of Health will decide by the summer of 2016 whether to include "intractable pain," as defined by Minnesota law, among the medical conditions that qualify for cannabis treatment. If a more general definition of chronic pain is added to the list of qualifying conditions, the number of customers could rise dramatically, to more than 100,000.

"That's the clear opportunity. You really need the long view," Kennedy said. "The real question is, is it financially viable for a company to make it through the next three or four years while they're waiting for the market to open up?"

Since there will be only two permits granted, winning one will be more valuable than in Colorado, which has 1,400 licenses, Woloveck said. And if history in other states is any guide, the law will be relaxed.

Rep. Pat Garofalo, a member of the state task force on medical cannabis, said he worries that the law has created a set of unhealthy incentives for investors.

"What they're banking on is that the law regarding the customers who have access to this will be expanded, but that the cap on the number of people allowed to provide this product will be maintained," Garofalo said. "They're betting on their ability to change future law, which is a softer way of saying crony capitalism."

Still murky

The shifting rules, legal complexity and long-term potential of marijuana are attracting lawyers to the industry.

Marijuana is still illegal by federal law, and banks are afraid to process debit and credit card payments for companies that sell marijuana, for fear of racketeering law.

Not only must companies navigate the contradiction between state and federal law, they will need guidance as regulators interpret Minnesota's law.

Companies must understand a new set of criminal and civil penalties. They must observe rules covering, for instance, how to dispose of stems, seeds and roots and how many cameras to put up in the room where patients pick up cannabis. It's possible they'll need to come up with specific blends of cannabis oil for specific types of patients. The draft rules, which run to 40 pages, are expected to change dramatically over the next 30 days, and probably beyond.

"We've seen cleanup legislation happen in every single market," Woloveck said. "Insomnia, chronic pain, post-traumatic stress disorder — that's another one that we usually see added on."

Eyeing the opportunity

The list of people and companies who are evaluating the market is diverse.

Members of the Bachman family, which owns the home and garden business, are interested, though not Bachman's Inc. or any of its officers.

"There is a group of interested family members who are looking into the issue," the company said in a statement.

Dave Haider, a founder of Urban Organics, an indoor farm in St. Paul, is looking at the business, since his firm already grows vegetables inside the old Hamm's Brewery.

"We're definitely evaluating the opportunity," Haider said. "It's not much different from our vision for providing quality natural food for the community."

Brinton, the veterinarian in Willmar, doesn't want to go solo in the marijuana business. But he thinks his warehouse and laboratory could play a part in the industry.

The Willmar City Council on Monday gave him the go-ahead to pursue it. He's open to selling the property, or partnering with someone to make marijuana products there.

"I don't know how to do pot, I'm a veterinarian," Brinton said. "I'm going to find a reputable company."

Adam Belz • 612-673-4405 Twitter: @adambelz

Olympic organizers unveil strategy for using artificial intelligence in sports