Mark Twain's explanation that "a mine is just a hole in the ground with a liar standing next to it" is a quote so brilliant and so often repeated that it's a shame he may never have said it.

Its enduring popularity extends even to mining executives chatting at an investment conference, where a CEO once got my whole table laughing with it. So even insiders realize that their industry has occasional credibility problems.

It also may help explain why mining regulators require a pot of money be set aside in advance, what's called "financial assurance," for any cleanup of environmental problems after the mine closes.

Late last week, the voluminous environmental impact report for the first project in what could be a major expansion of mining in Minnesota, PolyMet Mining's proposed copper-nickel mining operation near Hoyt Lakes, was released, but without much that was meaningful about financial assurance.

It's baffling that over a decade into the project's evolution, the public still knows next to nothing about the financial assurance provision. It's hardly trivial, given that the proposed mining and processing operation could require the treatment of water for more than 500 years.

The idea behind requiring financial assurance to make sure there's money to contain and clean up polluted sites is really pretty simple. A mine is operated by a corporation that could go bankrupt, or fold up like a circus and leave town once the money has all been made and the mine is played out.

In either case, it would be leaving behind a mess.

So regulators, who otherwise would have to step in with the taxpayers' money to close down a polluting mine site or let it keep bleeding, have insisted that the mine operator set aside money for reclamation of the mine once operations cease. If not exactly putting the land back the way it was before mining, the reclamation process at least cleans up the site and stabilizes it.

PolyMet's NorthMet project is planned to consist of a mining site where the rock is dug up as well as a processing facility just down the road that's a refurbished taconite processing plant. Reclaiming those sites once mining ceases would be a big expense all by itself, but in the case of PolyMet there is a second financial assurance challenge related to clean water.

Mining for copper and nickel typically requires monitoring and cleaning of water. The draft environmental report said there could be a need to monitor and treat the water for a minimum of 200 years at the site where PolyMet plans to be digging and a minimum of 500 years at the nearby processing plant site.

At the risk of stating the obvious, 500 years is a very long time. It was 500 years ago when the Italian diplomat Niccolò Machiavelli sat down and wrote a little how-to book for political leaders called "The Prince."

The task of providing financial assurance begins with estimating what it will cost to shut down operations, contain the waste, monitor the water quality and treat the water that becomes polluted. With that cost estimate in hand, the mine operator then arranges for enough money to be available, such as through a trust account, to pay for all the costs more or less forever.

The big environmental report just released, called the supplemental draft environmental impact statement, has just a small section on financial assurance that says next to nothing.

The feds wanted it

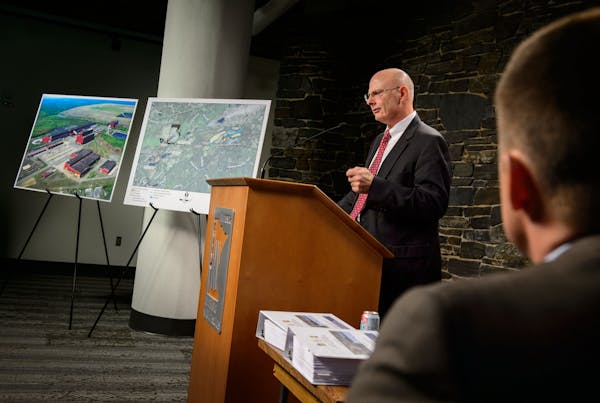

Jess Richards, director of the Division of Lands and Minerals of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, explained that what's in the report is there because federal regulators asked for it.

It takes up a little over three pages in a report so big that just the glossary alone is nearly five times bigger. It has a one-line table, showing estimates of cost if the mine were to close at the end of year one, at the end of year 11, or at the end of year 20. The high end of the cost-estimate range is $200 million.

It also estimates post-closure annual monitoring and maintenance costs of $3.5 million to $6 million.

The report is silent on how these amounts were determined, or how PolyMet could be sure no more than $6 million will be needed to get the job done 198 or so years from now.

"The [financial] model is much more sensitive to the operating costs than it is to the replacement capital costs" of assets like new water treatment plants, said David Chambers, who heads a Montana-based nonprofit that advises public interest and environmental groups on technical mining questions.

If operating a water treatment facility costs $1 million a year, the financial assurance for PolyMet should be easily manageable, he said. "But if that operating cost got up to $10 million a year, that is pushing $1 billion to pay for that. That's why at PolyMet it becomes an issue."

Attorney Kathryn Hoffman of the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy explained that environmental groups have repeatedly questioned the DNR on why far more detailed financial assurance analysis wasn't made part of this big study on the environmental impact of the mining operation.

The DNR's Richards said the public needs to be a little more patient. His agency has plans to hire at least one if not more consultants to help evaluate PolyMet's proposed financial assurance plan when the company applies for a permit to mine.

"We recognize, too, that fundamentally, financial assurance is one of the most important parts of the discussion for PolyMet," Richards said.

That's certainly a fair statement, and for outsiders like Chambers the more that's eventually disclosed about the assumptions and analysis PolyMet is using, the better.

As a fourth-grade math teacher might say, PolyMet can't just write down the answer. It has to show its work.

"I don't think it's a bad place to mine," Chambers said of the PolyMet site. "But if you are going to do it, you need to do it right."

lee.schafer@startribune.com • 612-673-4302

Schafer: What do you really need to retire?

Schafer: How doing business can be a bit more like Christmas morning

Schafer: There won't soon be another opportunity to rethink the I-94 corridor

Schafer: The fruits of Honeywell's long-game dedication to quantum computer now being seen