This week the leaders of North America's two most populous countries are due to meet for a neighborly chat in Washington. The re-elected Barack Obama and Mexico's president-elect, Enrique Peña Nieto, have plenty to talk about: Mexico is changing in ways that will profoundly affect its big northern neighbor, and unless America rethinks its outdated picture of life across the border, both countries risk forgoing the benefits promised by Mexico's rise.

The White House does not spend much time looking south. During six hours of televised campaign debates this year, neither Obama nor his vice president mentioned Mexico directly. That is extraordinary. One in 10 Mexican citizens lives in the United States. Include their American-born descendants and you have about 33 million people, about 10 percent of America's population.

In terms of GDP, Mexico it ranks just ahead of South Korea. In 2011 the Mexican economy grew faster than Brazil's -- and will do so again in 2012.

Yet Americans are gloomy about Mexico, and so is their government: three years ago Pentagon analysts warned that Mexico risked becoming a "failed state." That is wildly wrong. In fact, Mexico's economy and society are doing pretty well. Even the drug-related violence, concentrated in a few areas, looks as if it is starting to abate.

Mañana in Mexico

The first place where Americans will notice these changes is in their shopping malls. China is by far the biggest source of America's imports. But wages in Chinese factories have quintupled in the past 10 years and the price of oil has tripled, inducing manufacturers focused on the American market to set up closer to home. Mexico already is the world's biggest exporter of flat-screen televisions, BlackBerrys and refrigerators, and is climbing up the rankings in cars, aerospace and more. If present trends continue, by 2018 America will import more from Mexico than from any other country. "Made in China" is giving way to "Hecho en México."

The doorway for those imports is a 2,000-mile border, the world's busiest. Yet some American politicians are doing their best to block it, out of fear of being swamped by immigrants. They could hardly be more wrong. Fewer Mexicans now move to the United States than come back south. America's fragile economy (with an unemployment rate nearly twice as high as Mexico's) has dampened arrivals and hastened departures.

Undervaluing trade and overestimating immigration has led to bad policies. Since Sept. 11, 2001, crossing the border has taken hours where it once took minutes, raising costs for Mexican manufacturers and thus for American consumers. Day trips have fallen by almost half. More crossing-points and fewer onerous checks would speed things up on the American side; pre-clearance of containers and passengers could be improved if Mexico were less touchy about having American officers on its soil (something which Canada does not mind). After an election in which 70 percent of Latinos voted for Obama, even America's immigrant-bashing Republicans should now see the need for immigration-law reform.

No time for a siesta

The least certain part of Mexico's brighter mañana concerns security. This year has seen a small drop in murders. Some hot spots, such as Ciudad Juarez, have improved dramatically. A third of Mexico has a lower murder rate than Louisiana, America's most murderous state. Nevertheless, the cartels will remain strong as long as two conditions hold. The first is that America imports drugs -- on which its citizens spend billions -- which it insists must remain illegal, while continuing to allow the traffickers to buy assault weapons freely. American politicians should heed the words of Felipe Calderon, Mexico's outgoing president, who after six years and 60,000 deaths says it is impossible to stop the drug trade.

The second black spot is that Mexican policing remains weak. If Peña is to keep his promise to halve the murder rate, he must be more effective than his predecessor in expanding the federal police and improving their counterparts at state level.

But that is just one of several issues that will test Peña. He cannot achieve his ambition to raise Mexico's annual growth rate to 6 percent by relying solely on export manufacturing. Upping the tempo requires liberalizing or scrapping state-run energy monopolies, which fail to exploit potentially vast oil and gas reserves. Boosting Mexico's poor productivity means forcing competition on a cozy bunch of private near-monopolies -- starting with telecoms, television, cement and food and drink. That means upsetting the tycoons who backed his campaign.

Facing down interests within his own party may be Peña's hardest task. The head of the oil workers union is a PRI senator. The teachers union, which is friendly with the party, is blocking progress in education. Labor reforms have been diluted by PRI congressmen with union links.

Peña, a good performer on the stump, should appeal beyond the PRI to a broad consensus for change among Mexicans. Time will tell if he measures up to the task. The country is poised to become America's new workshop. If the neighbors want to make the most of that, it is time for them to take another look over the border.

Participant, studio behind 'Spotlight,' 'An Inconvenient Truth,' shutters after 20 years

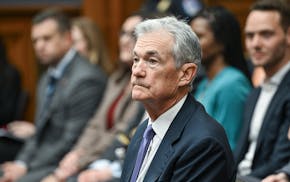

Fed's Powell: Elevated inflation will likely delay rate cuts this year