The state is segregating thousands of disabled adults in isolating jobs and homes. Many feel trapped, unable to lead independent lives.

WILLMAR, MINN.

In a field on the outskirts of town, a man with Down syndrome is spending another day picking up garbage.

He wears faded pants, heavy gloves, a bright yellow vest and a name tag that says "Scott Rhude."

His job is futile. Prairie winds blow debris from a landfill nearby faster than he and his co-workers can collect it. In the gray sky overhead, a turkey vulture circles in wide loops.

Rhude, 33, earns $2 an hour. He longs for more rewarding work — maybe at Best Buy, he says, or a library. But that would require personalized training, a job counselor and other services that aren't available.

"He is stuck, stuck, stuck," said his mother, Mary Rhude. "Every day that he works at the landfill is a day that he goes backward."

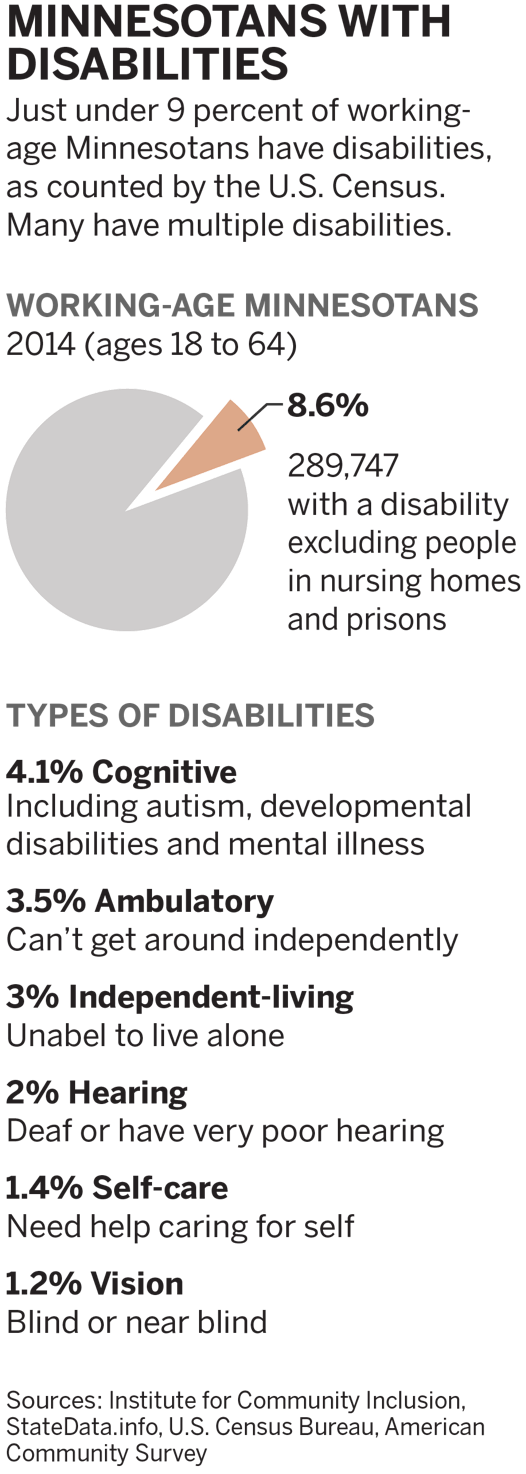

Rhude is one of thousands of Minnesotans with disabilities who are employed by facilities known as sheltered workshops. They stuff envelopes, package candy or scrub toilets for just scraps of pay, with little hope of building better, more dignified lives.

Many states, inspired by a new civil rights movement to integrate the disabled into mainstream life, are shuttering places like this. Not Minnesota. It still subsidizes nearly 300 sheltered workshops and is now among the most segregated states in the nation for working people with intellectual disabilities.

The workshops are part of a larger patchwork of state policies that are stranding legions of disabled Minnesotans on grim margins of society. More than a decade after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Americans with disabilities have a right to live in the mainstream, many disabled Minnesotans and their families say they still feel forsaken — mired in profoundly isolating and sometimes dangerous environments they didn't choose and can't escape.

Records examined by the Star Tribune bear them out. Minnesota pours $220 million annually into the sheltered workshop industry, consigning more than 12,000 adults to isolating and often mind-numbing work. It also relies more than any other state on group homes to house the disabled — often in remote locations where residents are far from their loved ones and vulnerable to abuse and neglect. And when Minnesotans with disabilities seek state assistance to lead more independent lives, many languish for months — even years — on a waiting list that is now one of the longest in the nation.

"We have entire communities of people with disabilities in this state who have zero choice," said Derek Nord, a University of Minnesota scholar who specializes in disability policy. "They live in closed systems with no obvious way out."

State officials defend Minnesota's record, saying it led the nation in closing large institutions for people with mental impairments and that it ranks high in the generosity of its disability benefits.

But in interviews with the Star Tribune, they acknowledged that people with disabilities deserve more control over their lives and said they are taking significant new steps to give them more choice in work and housing.

"Today, too many families believe their child, or their loved one, only has one option — a sheltered workshop," said Jennifer DeCubellis, assistant commissioner at the Department of Human Services. "So we have to undo that and make sure they understand there are other options. We have not done such a good job connecting people to those options."

Other states are far ahead of Minnesota. Vermont has abolished sheltered workshops and moved most of their employees into other jobs. States across New England place nearly three times as many disabled adults in integrated jobs as Minnesota. Washington offers disabled workers nine months of vocational training and career counselors.

"Nationally, the big river of change is flowing … toward increased integration," said Pamela Hoopes, legal director of the Minnesota Disability Law Center. "Sometimes it appears that we [in Minnesota] are meandering along the bank and getting hung up on the weeds.''

Safe, or trapped

The segregation starts early.

As a boy in special education classes, Scott Rhude showed talent with computers and photography. But once he graduated from high school, his mother says, he bounced from one segregated workplace to another, never quite escaping a system that has sometimes amounted to little more than what she calls "babysitting."

Away from his job, Rhude has built an independent life. He pays his own rent and shares a house with three friends in Willmar, a town of 19,600 west of the Twin Cities. He sings karaoke, goes on double dates and started his own book club. His bedroom is packed with trophies from Special Olympics events.

"I'm not afraid of anything," he joked recently, flexing his biceps under a poster of a professional wrestler in his bedroom.

But Rhude's pursuit of independence ends each morning when the city bus drops him off at West Central Industries, a sheltered workshop on the edge of town. From here, a van takes him to the Kandiyohi County landfill, where he spends the next five hours collecting trash on a hillside as big as two football fields.

Mary Rhude says she and her son hoped the roving work detail would broaden Scott Rhude's skills and give him exposure to other employers in Willmar. Instead, she says, it has become a "suffocating" experience that keeps her son isolated from the community.

Kristine Yost, a job placement specialist for people with disabilities, calls this system "the conveyor belt."

"It's heartbreaking," she said, "but time and again, young people get pigeonholed as destined for a sheltered workshop and then they can't get out."

Civil rights revolution

In 1999, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling, known as Olmstead, that prohibits states from unnecessarily confining people with disabilities in special homes or workplaces. In a broad reading of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the court said that fairness demands not just access to buses and buildings, but to a life of dignity and respect. People with a wide range of disabilities — including Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and autism — call it their "Brown vs. Board of Education."

In the ruling's aftermath, many governors closed state institutions for the disabled and the U.S. Justice Department sued Oregon and Rhode Island to close sheltered workshops.

But, 16 years later, the movement has yet to take hold in Minnesota.

Under sustained pressure from a federal judge, Minnesota this fall became one of the last states in the country to adopt a blueprint — known as an Olmstead plan — to expand housing and work options for people with disabilities. County officials and social workers have begun consulting disabled clients about their goals and interests. By 2019, the state expects counties to complete detailed, individualized plans spelling out work and housing options for thousands of disabled adults.

Yet even if it is executed successfully, the state's plan calls for only modest increases in the number of disabled adults living and working in the community. It makes no mention of phasing out segregated workshops and group homes.

Its employment targets, Hoopes said, are "woefully inadequate" and a "lost opportunity."

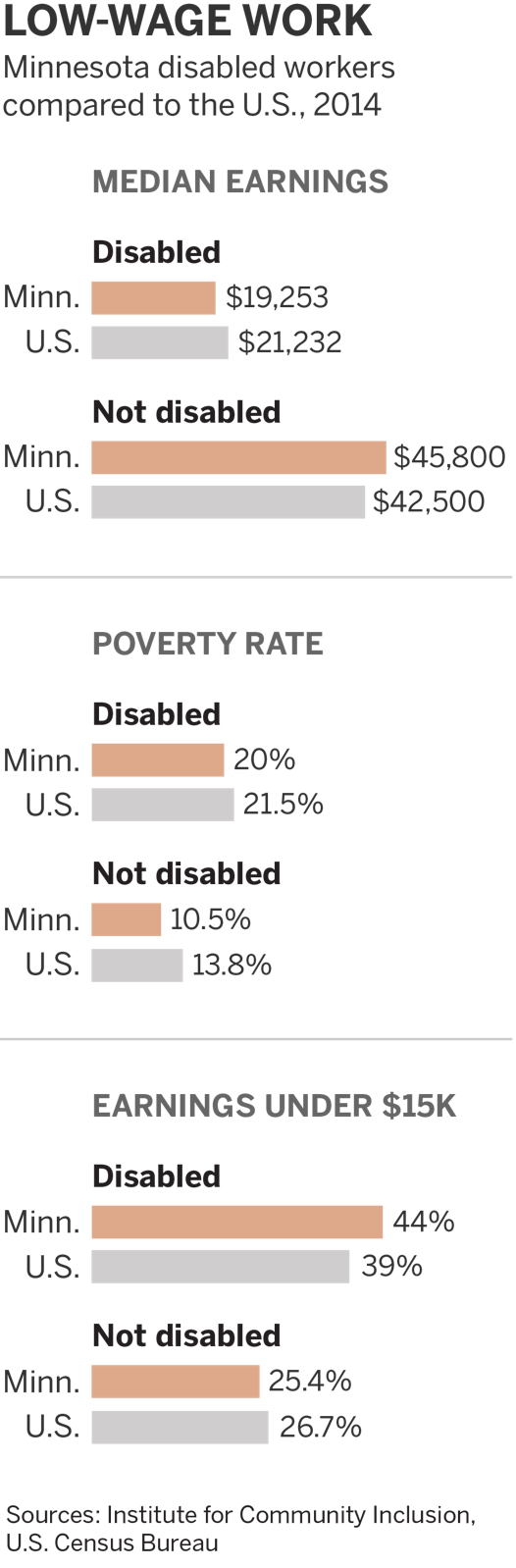

Some families defend sheltered workshops, saying they provide a safe place and a sense of accomplishment for young adults who cannot hold competitive jobs. Minnesota has a high overall employment rate for adults with disabilities, in part because of its sheltered workshops.

Others say the state is clinging to an obsolete and paternalistic practice.

"We have this mind-set in [Minnesota] that says protection trumps everything else, and we have to keep people in these isolated bubbles to keep them safe," said Mary Fenske, a disability rights advocate from Maple Grove who advises employees of sheltered workshops.

Sheltered workshops multiply

Sheltered workshops were designed after World War II to prepare people with disabilities for traditional employment. They caught on in Minnesota, and between 1970 and 1984 the sheltered workforce increased from 700 to 6,000 workers, including thousands of people who needed daily activities after the closing of state mental hospitals.

Today, state policy perpetuates the segregation.

Each year, Minnesota pays more than $220 million in state and federal Medicaid funds to scores of sheltered workshops and training programs, which have become a large and self-sustaining industry. They operate fleets of vans, partner with local group homes, and use a federal loophole that exempts them from minimum-wage law.

Most of Minnesota's sheltered workshops are nonprofits, but many hold business contracts with companies such as 3M to assemble or package products, while others provide janitorial services to local businesses. Even though they pay, on average, just $4.05 an hour, most could not survive without state subsidies to cover the cost of supervision and other services.

"If not for the government money, a lot of these [sheltered workshops] would be starved out of existence," said Jim Clapper, board chairman of Midwest Special Services, Inc., a sheltered workshop and day training provider in St. Paul. Clapper's son works at a sheltered workshop.

From a taxpayer's perspective, the workshop model is highly inefficient. It costs roughly $52,000 to create a sheltered workshop job that pays at least minimum wage, state records show. That's nearly 10 times the $5,300 it costs to help a disabled worker get a job in the community, according to a 2010 survey by the Department of Human Services.

"This all comes down to funding," said John Butterworth, director of the Institute for Community Inclusion, a research and training center at the University of Massachusetts. "If Minnesota spent this money on competitive employment, you would see more people working in typical workplaces earning typical wages."

If sheltered workshops prepared their clients for better jobs, they might justify the huge investment. But academic research and state reviews suggest they do not. When Minnesota's legislative auditor studied the industry in the 1980s, he found that only 83 of 3,000 sheltered workers graduated to competitive jobs. Today, research places the share at about 5 percent.

In fact, sheltered workshops can actually impede clients' progress by training them to be compliant and settle for mundane tasks, said Bryan Dague, a University of Vermont researcher who advises states on disability employment.

"All too often, a job in a sheltered workshop is a dead end," Dague said.

Factory work

Early one morning last spring, at a warehouse set amid cornfields near Fairmont, Minn., more than 30 workers with varying disabilities stood quietly in line, clutching their white time cards. A few checked their watches nervously.

At 8:15, a clipboard-wielding supervisor shouted, "It's time to get rollin'! Time to get rollin'!"

With its clockwork precision, this workshop operated by MRCI Inc. of Mankato shows how the industry has developed a keenly efficient model — but also why many of its employees find it suffocating.

Over the next eight hours, employees filled 3,600 plastic tubes with patriotic red, white and blue gumballs for Memorial Day sales at big-box retailers. They also arranged more than 50,000 cans of chicken into tidy piles as they tumbled down a fast-moving conveyor belt known as the "T-Rex."

Apart from managers occasionally yelling orders, the sprawling room was quiet but for the steady rat-a-tat of gumballs pouring into 12-inch tubes and the hum of a machine wrapping plastic around cans of chicken.

"Our workers are very well-behaved and task-focused," said Ramona Harper, the workshop's manager, as she walked the plant floor. "This is the best-kept secret in Martin County."

Next to many workers were small white sheets to track their productivity. Every so often, a manager stopped by and jotted down how many tubes each employee had filled with gumballs. Pay is calculated using the prevailing wage for similar work: A disabled worker who pours gumballs half as fast as a non-disabled person makes half the prevailing wage for light manufacturing, or about $5 an hour.

At noon, workers rushed into the cafeteria for plastic-wrapped sandwiches waiting under a heat lamp. On this day, the room buzzed with talk of two colleagues who "made it to the outside." One landed a job at Wal-Mart and the other was bagging groceries at a local supermarket for $9 per hour.

"It's the success stories that give us hope that someday we can make it out of here," said Dustin Leibfried, 42. "Because there are some days when you feel like you're just racing, racing to catch up. Most of us want out."

DIFFERENT WORLDS

Suzanne Sukalski is a breakfast hostess at a hotel in Fairmont, and Erin Ebert works in a sheltered workshop on a cleaning crew. They both have Down syndrome, but have very different job outlooks.

Read full storyA closed system

John Wayne Barker was working his way through the brightly lit lunchroom of Merrick Inc., where he has been executive director for the past 17 years. Every few steps, a worker stopped him for a high five or a hug.

Barker is a vocal defender of sheltered workshops, and his expansive facility is considered a model for the industry. It operates an assembly line where about 100 workers perform tasks like inserting greeting cards into envelopes for sale at grocery stores. But it also offers an array of "life enrichment" services, from music and pet therapy to yoga and gardening, for people who may be unable to work.

If the workshop closed, many of its employees would be "at home, staring at the wall,'' deprived of their sole source of wages and social interaction, Barker said.

"Without our program, virtually nine out of 10 people we're serving would have no consistent daytime activity,'' he said. "Nobody [here] is trapped or unhappy.''

Some parents agree. Ivan Levy said his 26-year-old son, Jason, who has autism and a developmental disability, has improved his social skills and self-confidence since coming to work at Merrick five years ago. After years of job coaching, he earns minimum wage in Merrick's recycling center.

"If you closed the workshop, Jason would go from being in an environment with a lot of support and a lot of interaction to one with zero support and zero interaction," said Levy, an attorney in St. Paul. "He'd be sitting at home, watching television or playing video games all day."

But for a large share of Minnesota's disabled workers, that's simply not true. At sheltered workshops subsidized by Minnesota's state workforce agency, as many as 45 percent of employees simultaneously hold other jobs in the community for at least minimum wage, according to an internal analysis. When Vermont closed its last sheltered workshop in 2002, social workers found jobs for 80 percent of the workers.

"The numbers show that a lot of people [in workshops] can do real work for real wages if given the opportunity," said Jon Alexander, a supported employment provider in Little Canada.

That includes people like Larry Lubbers, 61, who made $15 an hour moving shopping carts at a Rainbow Foods until he suffered a back injury. Unable to find other work, Lubbers, who has an intellectual disability, said he didn't object when the county suggested a sheltered workshop.

Yet Lubbers says he remains shocked by his low pay. He now makes less than $30 a week doing menial tasks such as inserting straws into plastic bags.

"It's out of sight, out of mind,'' Lubbers said one day as he waited for a van to work from his home in Inver Grove Heights. "Once you walk into a sheltered workshop, you become invisible.''

Breaking out of the system can be extremely difficult. Because their wages are so low, many sheltered workshop employees can't afford their own apartments or transportation. A 2010 state survey found that nearly 80 percent rely on their employer as their primary source of transit. In fact, a half-dozen sheltered workshops also run their own group homes; at least one, Functional Industries in Buffalo, Minn., shuttles people to its sheltered workshops from its group homes in its own vans.

"It's a closed system," said Mary Kay Kennedy, executive director of Advocating Change Together, a disability rights group in St. Paul. "It's so safe and predictable that a lot of people never get to explore other options and realize their true potential."

Handing out résumés

Kenisha Conditt, 27, who has a developmental disability, went straight to work at Midwest Special Services in St. Paul after graduating from youth vocational training. For the past five years, she has been assigned to a cleaning crew that collects trash, mops floors and cleans toilets at area businesses.

On a recent morning, Conditt's team marched in a line through the parking lot of an industrial park in Minneapolis, carrying large plastic jugs in one hand and long-handled pincers in the other. With a supervisor watching, they plucked plastic bags, cigarette butts and shattered glass from the blacktop.

"You missed one, Kenisha!" the supervisor called, pointing to a rusty nail.

After dumping her last bucket of trash and mopping the entryway of a bus terminal, Conditt returned to Midwest's gated campus in St. Paul, where she spent the next several hours killing time before a Metro Mobility bus arrived to take her home. Sitting with a group of co-workers on a row of plastic chairs, she stared ahead stoically as a woman with an accordion played "Goodnight Irene" and then the workshop's special song, "Midwest Special Services is where I like to be … "

When the song ended, Conditt and the others filed quietly back to a row of desks full of puzzles and games.

"Five years of this, and I'm ready to move on," she said. "I don't want to spend the rest of my life cleaning toilets."

A few days later, Conditt seemed transformed. On Sundays she helps teach children at Christ Temple Apostolic Church in Roseville. She laughed, sang and read children's books as toddlers crawled over her lap and shoulders.

"Kenisha has gifts that people at the workshop never see," said her mother, Antoinette Conditt.

On the drive home from church, they spotted an Old Country Buffet with a "Help Wanted'' sign in the window. Her mother pulled over. Conditt darted across the parking lot.

Stepping into the restaurant's lobby, she smoothed her blue skirt, smiled broadly, and asked if she could speak with the manager. In one of her hands Conditt held tightly to a folder filled with copies of her résumé.

She takes them everywhere she goes.