Why is there a new cellular pole in my Minneapolis neighborhood?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Hundreds of new cellular poles have swiftly blanketed Minneapolis neighborhoods in recent months, illustrating how the latest generation of wireless technology will also reshape the urban landscape.

Cellular providers are racing to roll out fifth generation wireless technology, known as 5G, which will dramatically boost internet speeds on smartphones and other devices. 5G requires many new antennas across the region to deliver all that data, whether affixed to street lights and buildings or atop new standalone poles.

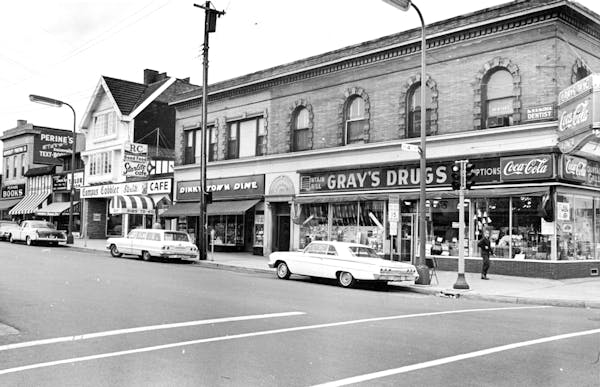

The sudden appearance of new poles rivaling the height of nearby homes in Minneapolis — with little public notice — prompted one anonymous reader to contact Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's community reporting project fueled by great reader questions. The reader wanted to know their purpose and why the poles are spaced so close together.

The short answer is that Verizon Wireless is deploying a type of 5G technology in Minneapolis neighborhoods that allows for the greatest speeds but travels the shortest distances. The proliferation of these standalone poles — Verizon now owns more than 700 of them in the city — was aided by a 2017 state law that eased regulations on smaller cell sites. Protections in that law for single-family neighborhoods were ultimately moot because Minneapolis eliminated single-family zoning.

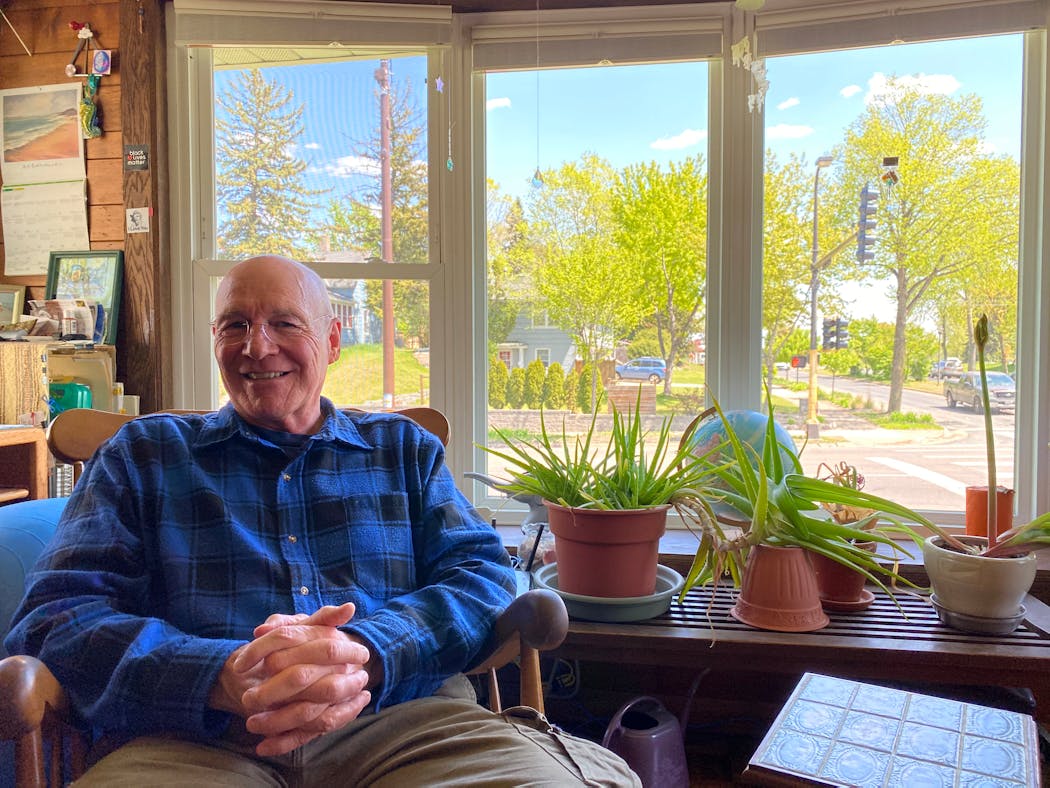

"My number one complaint is it's dumb technology for our neighborhoods," said Roy Vanderwerf, another Minneapolis resident who has been inquiring about the poles. "And number two, they're doing it without anybody's say-so."

Vanderwerf first learned of the issue in late 2019 when he noticed workers marking the boulevard outside his sun room, where he regularly watches birds. Now a brown tower, topped by an antenna, obstructs views of a spruce tree where he sometimes spots hawks and eagles.

A new generation of cellular

5G is capable of delivering speeds that are 10 to 20 times faster than the fourth-generation (LTE) technology that consumers are accustomed to today, according to professor Feng Qian, who specializes in wireless technology at the University of Minnesota. That could help autonomous cars communicate, improve teleconferencing, enable new uses for virtual reality, and make it possible to download a high-definition movie in 30 seconds, he said.

Most smartphones still can't take advantage of it — Apple released the first 5G-capable iPhone last fall — but that will change as people upgrade.

"I will say maybe in four to five years ... 5G will be a very common technology — at least in major cities, major urban areas," Qian said.

Cellular antennas have been moving closer to the end users with each new generation of wireless technology, said Mike Dano, editorial director of 5G and mobile strategies at Light Reading, a trade publication covering the telecom industry. Once affixed to massive cellular towers, antennas now hang from school buildings, street lights and standalone poles. The increasing demand for cell service and roll out of 5G is requiring a lot of new infrastructure, Dano said.

Unlike 3G and 4G, the fifth generation technology allows cell companies to use a variety of frequencies — each with its own advantages, Dano said. Verizon initially invested heavily in acquiring higher frequencies, he said, which travel the shortest distance but allow the fastest speeds. Hence the dense network of poles in Minneapolis.

Verizon spokesman Chris Serico said the company has been adding more cell sites to support the "dramatic increase in voice and data traffic on our network." The company is marketing this improved service in parts of the Twin Cities as "5G Ultra Wideband."

"Its ultrafast speeds and reduced lag time ... can give smartphones new capabilities for multi-player gaming on the go, streaming 4K movies and video, chatting in HD and more," Serico wrote in an e-mail. The company is also marketing it as a home internet alternative.

T-Mobile, AT&T and Verizon are also rolling out 5G on so-called "mid-band" frequencies, Dano said. These travel farther and can often take advantage of existing antenna locations, though Dano said they may also require new infrastructure.

Minneapolis isn't alone. Providers are installing new small cellular sites in the right of way of other cities like St. Paul and Bloomington, but in much smaller numbers so far.

The legislative debate

Minnesota is one of more than two dozen states that have passed laws in recent years streamlining regulations for the smaller-scale antenna sites used by 5G, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. The 2017 Minnesota law was followed a year later by a similar Federal Communications Commission order, covering the entire country.

The law states that the small cellular antenna sites are an allowed use of the public right of way. It limits cities from dictating where the facilities are placed, creates a 90-day clock for approving or denying permit applications, and caps what cities can charge in rent for attaching antennas to city-owned structures.

"The industry just wrote their own ticket, wrote the bill the way they wanted [to]," said Sen. Scott Dibble, DFL-Minneapolis. "And the municipalities, the cities, had nothing to say about it."

Dibble, who has introduced a bill to weaken some provisions of the law, says he has heard from alarmed constituents about poles going up in their boulevards. They tell him the poles are unattractive, he said, but also express concerns about the health implications of the technology.

The perceived health risks of radiation from 5G towers has fueled activism around the country. The American Cancer Society has stated that there is "isn't a lot of evidence" to support the idea that cell towers are a health risk, but the organization believes more research is needed on the issue.

Rep. Marion O'Neill, who oversaw final negotiations on the legislation, rejects the idea that cities were left out of the process. She provided a list of two dozen changes that were made to accommodate concerns from The League of Minnesota Cities, which was ultimately neutral on the legislation.

"Every time the League raised a concern, we did not move forward until we got consensus that they were OK with that policy," said O'Neill, R-Maple Lake.

Changes included extending the timeline to act on permit applications, limiting the height of new cell poles and allowing cities to require a "conditional use" permit for poles in historic districts and areas "zoned for single-family residential use."

Requiring a conditional use permit for poles in residential parts of Minneapolis would have likely triggered a public hearing and citizen input. But the city chose not to require one because it was developing the 2040 Comprehensive Plan, which would ultimately eliminate single-family zoning, according to city spokesman Casper Hill.

Hill said that permit process would not have benefited apartments and non-residential properties.

"Instead, Minneapolis Public Works worked with Verizon to expand their notification processes to the properties affected near a pole installation," Hill wrote in an e-mail.

Vanderwerf complained to Verizon about the pole outside his house and received a letter explaining that Minneapolis has seen a large increase in wireless device use that requires more capacity. He has since received a Verizon mailer advertising for "5G Home Internet," though he is already satisfied with his US Internet fiber service.

"It's a waste," said Vanderwerf, looking out his window. "Because I don't anticipate very many people using that. I really don't."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why does Minneapolis keep planting trees under power lines?

Why doesn't the city of St. Paul plow its alleys? (Minneapolis does!)

Why do we have water towers and what do they do?

How did Minneapolis end up with a street named after Xerxes, a Persian king?

Why is 'southeast' Minneapolis actually northeast of downtown?

Are roundabouts really safer than traditional intersections?

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify The League of Minnesota Cities' position on the legislation.