As the zebra mussel continues its destructive march across Minnesota’s waterways, researchers are counterattacking with sophisticated chemical and genetic weapons.

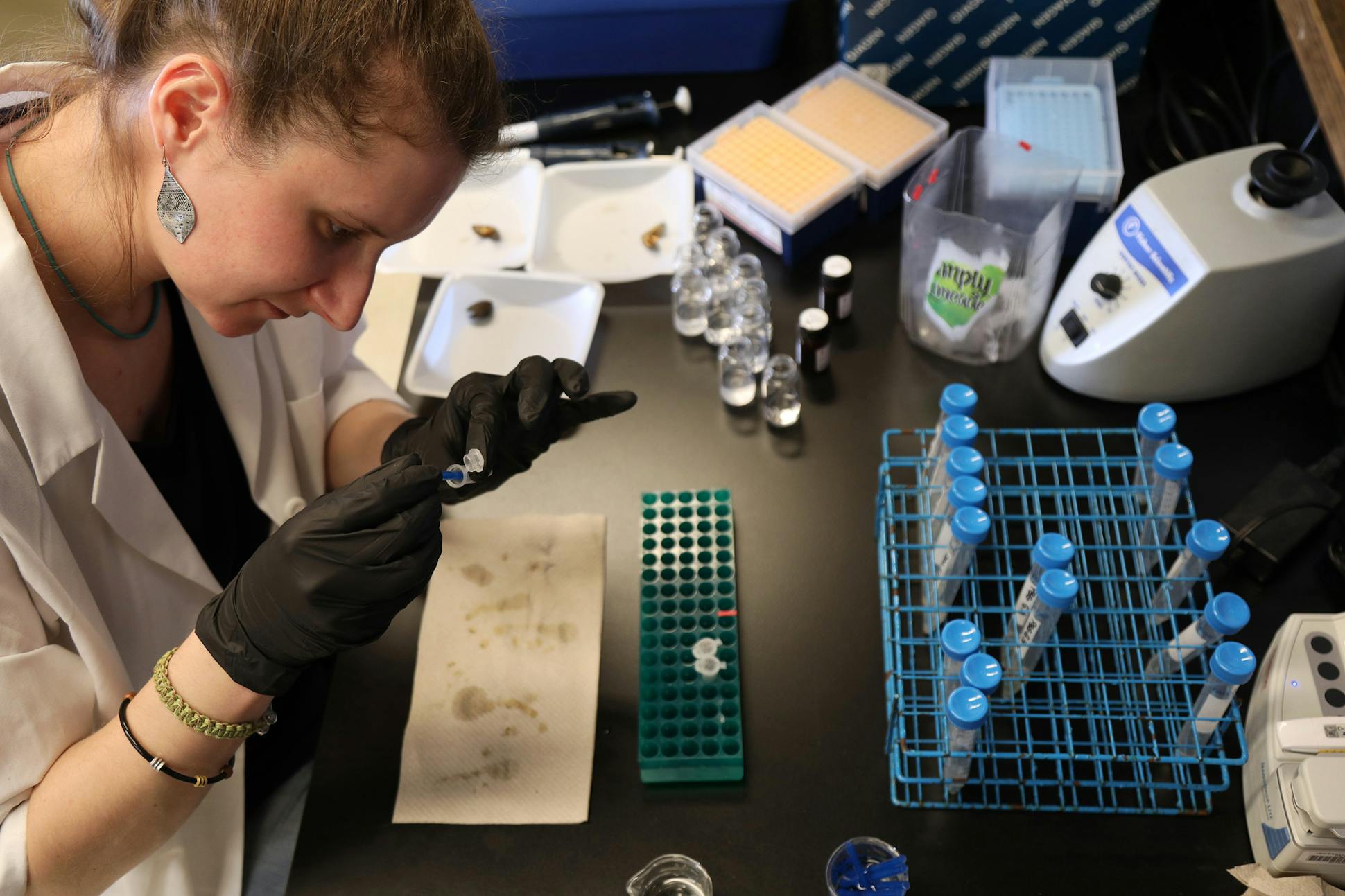

Kenny Beckman's laboratory at the University of Minnesota's Cancer and Cardiovascular Research Building features some the world's most sophisticated gene-mapping tools, including a newly arrived $1 million sequencer that will accelerate groundbreaking work on DNA.

These instruments also represent the most promising front in a high-speed scramble to halt the spread of zebra mussels, which for two centuries have wreaked biological havoc in European and North American waterways.

Beckman's lab expects to release later this summer the first ever sequence of the entire genome of the highly invasive mollusk. Researchers say it will be a major advance in the race to unleash sophisticated chemical, biological and genetic weapons against a foe that, in the 25 years since it appeared in Minnesota's lakes and rivers, has been pursued mostly by boat inspectors and specially trained dogs.

Scientists at the U's BioTechnology Institute, for example, are awaiting the DNA profile to speed their hunt for a naturally occurring bacterium or parasite that will kill zebra mussels.

"Is it biological warfare? Yes," said professor Michael Sadowsky. "I think we can get it to work."

Meanwhile, scientists at a federal lab in La Crosse, Wis., eagerly anticipate employing the genetic blueprint to develop gene-tinkering counterpunches that could, in effect, cause zebra mussels to self-destruct.

The goal is not just to unravel the genome, Beckman said.

"In this case you are decoding the mussel so you can get rid of it," Beckman said. "It's hard to believe something mind-blowing won't come out of this."

Much is riding on these new efforts to stop a shellfish that has proved to be stealthy, prolific and seemingly invincible. Since first appearing in the Great Lakes, they've spread as far east as New York's Hudson River; as far south as Louisiana, where they clog utility intake pipes in the Mississippi River, and as far west as California, where pumps, dams and aqueducts are threatened in Los Angeles. The estimated economic impact so far: More than $1 billion and climbing.

The federal government and taxpayers in Minnesota and elsewhere are investing tens of millions of dollars annually to contain the outbreak, which shows few signs of slowing.

Developments in the lab sometimes fizzle in the field, so there's no certainty that gene sequencing will lead to a breakthrough in the race to slow the spread of zebra mussels, or eradicate them altogether. A few years ago researchers doused zebra mussels in a west metro lake with a chemical cocktail that seemed promising – until the mussels began appearing in other parts of the lake.

A targeted, high-tech assault on the mussels also is likely to draw opposition from some scientists, environmental advocates, policymakers and others who fear that attacking zebra mussels with genetically modified organisms or pathogens could produce unintended consequences.

"Let's be as careful as we can be," said Pat Mooney, executive director of Canadian-based ETC Group, a global watchdog on ethics related to new technologies. "You have to know whether it could destroy other species."

Pressure from resort operators, property owners, industrial water users and weekend fishing and boating enthusiasts to halt the spread of zebra mussels is intensifying. Two new infestations discovered this month means about 275 Minnesota lakes and rivers are confirmed basins for the striped mussels, in an outbreak that's still growing by 20 to 30 waterways each year.

The stakes are high, said Nick Phelps, co-director of the Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Research Center (MAISRC).

"If we don't do anything," he said, "everything that can be invaded, will be."

Pinpointing the source

Phelps' lab, on the U's pastoral St. Paul campus, works closely with federal researchers and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR), and will play a key role in the zebra mussel counterinsurgency.

The center just announced six new studies to thwart aquatic invasive species. Three will target zebra mussels.

One initiative will analyze atoms and molecules taken from tissues of walleyes and other fish to show how zebra mussels and another invasive species, spiny waterfleas, destroy the food chain in Minnesota's largest walleye lakes.

Michael McCartney, lead zebra mussel researcher at MAISRC, has used preliminary genetic data to sort out family ties among mussels in different lakes.

These "genetic clusters" reveal that lakes are most likely to be infested by boats or equipment carrying hitchhiker mussels from nearby lakes, rather than more distant, heavily infested lakes such as Mille Lacs or Minnetonka – despite the high volume of boats trailered into and out of those waters.

With the zebra mussel's full DNA readout, McCartney said, they'll be able to pinpoint still more specifically a lake's invasion sources, and use that information to better manage various travel routes to slow down or head off more infestations.

Preparing their arsenal

Federal researcher Diane Waller was overwhelmed when she first waded into Lake Minnetonka's Robinson Bay to collect adult mussels for her experiments.

Picking up a single stone with a coarse texture, she quickly realized its thousands of tiny bumps were larval-stage zebra mussels no bigger than grains of sand.

PLAN OF ATTACK

Lake Minnetonka alone is home to an estimated 166 billion zebra mussels, according to the Minnehaha Creek Watershed District.

"Their reproductive rate is incredible," Waller said.

Waller is a scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey's aquatic invasive species complex in La Crosse, where two dozen test aquariums are stacked around her lab and hundreds of zebra mussels cling to objects in each glass enclosure.

She's dousing the mussels with controlled doses of carbon dioxide administered through a hose, trying to determine which combinations of gas and water temperature kill zebra mussels, while leaving native mussels unharmed.

At some point, her experiments will shift to the field – probably in a confined area such as a boat landing, where the mussels exist but have not yet spread. It's possible, she said, that injecting CO2 in winter, under ice, might prove most effective.

Waller also has discovered that carbon dioxide sedates zebra mussels, leaving them more vulnerable to pesticides. Her colleague, Jim Luoma, is studying the effectiveness of four of them: Zequanox, a biopesticide; Earthtec QZ, a copper compound; Bayluscide, a chemical that kills sea lamprey; and toxic amounts of potassium chloride.

They're all proven to kill zebra mussels, but real-life applications in contaminated lakes haven't consistently wiped out entire colonies. To further that possibility, Luoma is measuring the pesticides' effectiveness and practicality when applied in various doses and water temperatures, and for differing durations. The goal is to remove guesswork for resource managers who apply the chemicals.

"Generally you get lethality with all of them," Luoma said. "Whether it's acceptable [to use] is for others to decide."

The questions will be even stickier for another researcher in the same facility, molecular biologist Chris Merkes.

Merkes, who trained to study cancer and was first assigned by USGS to research Asian carp, believes gene editing tools will make it possible to re-engineer the reproductive code of zebra mussels.

Hypothetically, gene splicing could create mutant zebra mussels that are unable to produce female offspring. Released into a lake with wild zebra mussels, their offspring would inherit the broken gene, and eventually the mussels would be daughterless and die out without endangering non-target species.

Merits of this so-called gene drive technology, or "mutagenic chain reactions," were debated last year at the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity. Many scientists wanted a moratorium placed on any environmental release of a gene drive, but no consensus emerged.

Dana Perls, a technology policy campaigner for the environmental advocacy group Friends of the Earth U.S., said the call for a moratorium reflects deep concerns that genetically modified organisms might unleash unintended, irreversible consequences.

Said Merkes: "We're getting asked a ton of questions, and that's good."

He said the soon-to-be-decoded zebra mussel genome also will open the door to experiments with genetically coded messenger molecules that could be released into water like chemicals. The molecules would trigger the zebra mussels to self-destruct – conceivably by disrupting the function of their hairlike "byssal" threads, which allow them to stick to objects.

Or the messenger molecules could throw off the timing of a female's egg release.

"It's like a chemical treatment, but super, super specific only to zebra mussels," Merkes said.

'Is it right for us?'

Use of genetically modified organisms to combat zebra mussels would require lengthy ethical, ecological and biomedical reviews.

The potential for collateral ecosystem damage is a central question in all of this research, said Becca Nash, associate director of the U's aquatic invasive research center.

"Technology has moved ahead so fast, we have to ask: 'Is it right for us to use it?' " Nash said.

Even Waller, the USGS researcher in La Crosse, acknowledges being worried about the harmful effects that attempts to eradicate zebra mussels might have on native mussels, the objects of her life's work.

Because zebra mussels kill native mussels by smothering them, allowing the invasive mussels to proliferate unchecked isn't a viable alternative, Waller said.

Minnesota cabin owner Bob Iversen, who is highly active in Cass County to stop zebra mussels from spreading, said some people already doubt that the spread of zebra mussels can be stopped.

Even if the mussels can't be killed out right now, Iversen and others, like DNR research scientist Gary Montz, say it's vital to slow down the migration until eradication is workable.

"I think we are looking at a five- to 10-year plan at best for any headway to kill zebra mussels," said Iversen, whose family has vacationed and lived on Ten Mile Lake in Hackensack since 1946. "Until then we are going to do the best we can."

Montz, an expert on aquatic invertebrates, believes the breadth of research underway can stop an all-out eruption of zebra mussels across thousands of Minnesota's pristine waterways. Until then, the more lakes they invade, the harder it will be to wipe them out, he said.

"A lot of people have spent a lot of time and a lot of money looking for that silver bullet and we still don't have it," Montz said.